Umbilically-connected.

After many years of marriage, I have slowly seen that my wife Meg’s soul is bound up with the souls of her children. It cannot be otherwise, and while it is always wonderfully and sometimes painfully complex, it is the way it is and ought to be.

As it is for everyone everywhere.

Set amidst the ages-long conflict between Jew and Arab — “blood brothers” they are, in Elias Chacour’s insightful image — “The Other Son” is the story of the very tender connection of mother to child that is almost impossible to explain apart from the physiologically and psychologically mysterious connection formed in utero, and beyond. A poignant account of two families, one in Tel Aviv and one in the West Bank, whose hopes and histories are inextricably twined together, a very personal reality that reflects the very public reality.

Two mothers gave birth in the same hospital 18 years earlier during a scud attack in the Desert Storm War of the early 1990s. In the confusion of care, their infant sons were switched, the Jewish son given to the Palestinian family, the Palestinian son given to the Jewish family. Years pass, long loves develop, the deepest possible bonds form — and it is this tension that forms the drama of the story.

While the issue of land and people is necessarily political, the film is not politicized. No points are scored for one people over another. If it has a message, it is simply that Jew and Arab are human beings first, and their lives — past, present, and future — are inseparable. Knowing that, what will we do?

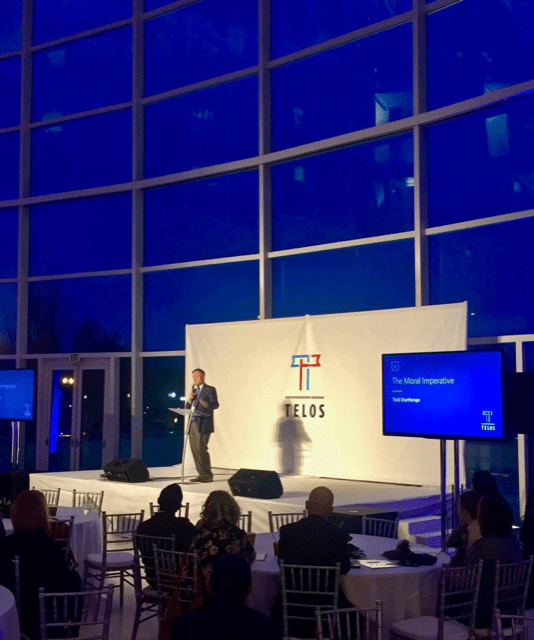

We were sitting beside our good friends and neighbors, Judi and Todd Deatherage, in our local art house theater. Given their lives and loves, seeing the film together made it specially significant; Todd had just returned from more than two weeks in the Middle East on behalf of the Telos Group, which offers “uncommon experiences for the common good,” principally for Americans who want to understand what they do not understand.

Long a chief of staff on Capitol Hill and in the State Department, Todd’s own history in Israel has convinced him that most people in the United States simply do not realize the reality of life on-the-ground, and that has tragic consequences for everyone who calls the land of Israel “home.” He has spent so much time there over so many years, walking through the streets of Jerusalem and Bethlehem, and Ramallah and Hebron, that those who live there have become his dear friends, Jew and Arab alike.

Because of long-formed expertise developed in the realpolitik of Israel’s painful realities, Todd knows what most simply do not because they have not seen what he has seen and heard what he has heard. Instead, most have impressions and opinions shaped by social constructs that are rooted in political and theological paradigms that are unrelated to the harder work required for there ever to be “peace in Jerusalem.” That most of us assume a zero-sum game, that we must choose one side of this story over the other, is a short-term geo-political fiction. Both peoples have histories, both peoples have hopes, and both must be honored — if justice is to be done, if mercy is to be loved. And yes, if we are to walk humbly with God.

In the strange grace of “The Other Son,” this reality is played out. How can I possibly choose against my son? and what does it mean to choose for my son? Because, of course, the mothers were umbilically-connected to both sons, tearfully so. How could it not be? And if we have eyes that see, we will see that too, perhaps with our own tears.

And tears are right — especially these weeks, with the long simmering tension boiling over, with rockets flying again through the sky maliciously intended for “the other.” But it is the failure to see the other as my brother, as my “blood brother,” that makes this place and its people so full of pain and sorrow. As Todd and I have talked through the years, we have returned again and again to the reality that apart from grace — even a social and political grace — all we have is eye-for-an-eye and tooth-for-a-tooth, the law of the jungle in every century and culture.

Is there an another way? Yes, but it is born of a severe mercy. The last weeks I have been reading Apeirogon by Colum McCann, a very unusual novel about life-on-the-ground in Jerusalem and Bethlehem that is brought into tearful being through the Parents Circle, a group that has a very terrible qualification for membership, i.e. one must have lost a child to the conflict, and commit oneself to the hard work of reconciliation. One of the best writers of our day, in its 1001 chapters we are drawn into the anguish of two families whose daughters were killed by “the other,” but who have chosen the very difficult grace of forgiveness in the face of the most heart-aching grief. So many thoughts run through my heart as I read, but we are required to rethink the question which is at the center of the conflict, “Whose land is it anyway?”

Yes, two histories, two hopes, and both must be honored — anything less is a short-term geopolitical fiction.

Read reviews of Apeirogon at The Guardian, The New York Times, and The Arts Fuse.

(Pictured: Todd Deatherage at the annual Telos Group conference at the U.S. Institute for Peace, appropriately and importantly next to the State Department. This is something I wrote two years ago, and tragically nothing has changed. Horror upon more horror has happened in the last weeks, and all we can imagine is eye-for-eye, tooth-for-tooth, a short-term geopolitical fiction, and thousands of ordinary people suffer.)