Intrinsic, not extrinsic.

Somewhere in the American Southwest, I began to understand an idea that has run through my life for most of my life. A year earlier I had dropped out of college, and had spent the first year in a commune in the Bay Area of California, working on a magazine committed to analyzing contemporary culture. Week by week I hitchhiked between Palo Alto and Berkeley, listening into worlds and worldview, paying attention to gurus of all kinds who gave their best shot at making sense of making sense.

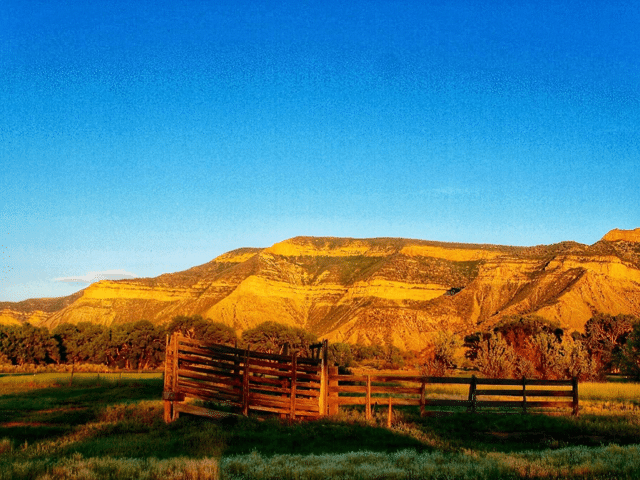

But all along I was planning to journey across America, hitchhiking from West to East, wanting to dig deeper into the questions that had taken me out of school and into the world. With my plane ticket for Icelandic Airlines and a backpack, I was on my way to Europe to learn what I could learn. On an August day, I had found a ride through the Four Corners— where Arizona meets Utah meets New Mexico meets Colorado —sweating from the summer sun on a long highway, reading a book that I had tried to read before. Written by a philosopher named Evan Runner, he argued that we can see the relationship of what we believe about the world to the way we live in the world in one of two ways, either extrinsically or intrinsically, i.e. that our commitments about all of reality, about God and history, about human nature, about justice and injustice, about right and wrong, are either as “add-on” to the stuff of life, or they are written into the very meaning of life. Extrinsic or intrinsic.

Though the day was too hot and the sun was too bright, a “light” was turned on that has only brightened over time. I still remember thinking, “That’s it, isn’t it?”

A week ago I took part in three conversations that were born along the road through the great mesas of Arizona, driving into the great mountains of Colorado. But these were all by Zoom, one in Bratislava, Slovakia, one in Oslo, Norway, and one in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Each one came into being because that difference between extrinsic and intrinsic has made a line-in-the-sand difference in the way I live and move and have my being— and years later the distinction runs through my thinking about everything, about every square inch of the whole of reality, to quote Abraham Kuyper, the prime minister in early 20th-century Holland.

Good people in these three places had asked me to talk with them about what I have written, bringing together groups via the wonder of Zoom to ask their questions about the possibility of a more seamless life, one with honest coherence between love and learning, worship and work. And listening to them, I loved them, wishing that I could sit and talk, or take a walk, hearing more of who they are, and why their questions mattered to them.

The third conversation was more than one group, as it was part of a global symposium that was brought into being by a philosophical tradition that calls itself, “Reformational,” which has its origins in the thinking of Kuyper (all imagined into being by Romel Regalado Bagares of the Philippines, and others). There is a lot of water under the bridges of history since 1900 when he was prime minister, someone who with remarkable integrity brought his personal life and public life together in an unusual vocation, but the online gathering brought 500 people from all over the world into three days of conversation about the most important things. Europeans, yes, but more Latin Americans in all, and Africans and Asians as well, with Americans and Canadians too, each in our own time zone, up early or late, willing to think together about the intrinsic meaning of beliefs about the world with the way we live in the world— from the arts to education, from economics to politics, from complex philosophical ideas to the nature of vocation and work.

And not surprisingly, it was the latter that drew me in, together with Alexei Gorbachev and Matthew Kaemingk to a group of people from literally over the world, many with their honest questions wanting their own honest answers— because of course all of us long to make more sense of who we are, of why we are, and of what we do with our lives, which are the questions of vocation and work for everyone everywhere.

Those questions made me leave college years ago, and were the reason I was reading an important if difficult book in the summer sun on a highway in the American Southwest, trying and trying again to understand the way the world is and isn’t, the way the world ought to be and someday will be.

(Photo of Mesa Verde National Park, with a cattle chute in its shadow, outside of Cortez, Colorado, near the Four Corners. My first memories of summer are from this geography on my grandparents ranch on the other side of the mesa, closer to Durango.)