A disposition to dualism.

The image caught me, thinking through my work last week. From teaching here in Washington, to speaking in Birmingham and Chicago, those words captured what I saw and heard. But what is dualism? and why does it matter?

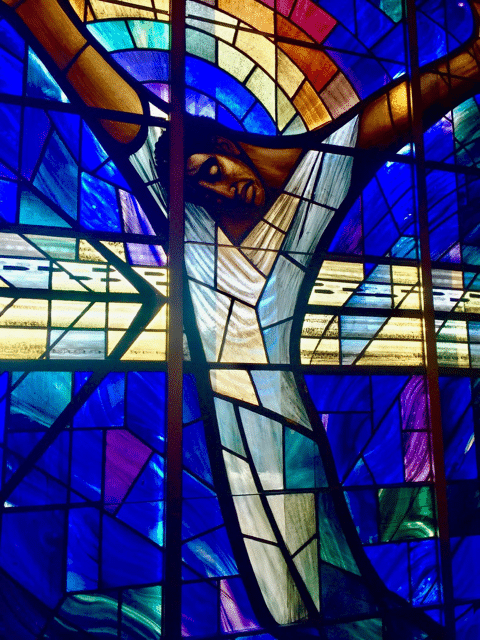

On Thursday morning this jumped into my face, standing in a large circle of folk in Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church gathered for what was called “a holy and historic moment” for the city, a prayer breakfast drawing black and white together for the sake of the city, hoping for the flourishing of their city. Hand-in-hand we sang, “Amazing Grace”— “I once was blind but now I see….” —with honest longing in our hearts, painfully aware of what the city has been, yearning for what the city can be and should be, gathered in a church building tragically known for the worst in the human heart, the malicious bombing that killed little girls in the midst of the civil rights tension of the 1960s. The former chief of police for Birmingham, an African-American woman, led us in the song, which itself seemed a remarkable window into what has changed in the city— no longer Bull Connor bullying his way through town, but the great-great granddaughter of slaves given the responsibility for the city’s safety. A hint of hope in every important way.

On Thursday morning this jumped into my face, standing in a large circle of folk in Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church gathered for what was called “a holy and historic moment” for the city, a prayer breakfast drawing black and white together for the sake of the city, hoping for the flourishing of their city. Hand-in-hand we sang, “Amazing Grace”— “I once was blind but now I see….” —with honest longing in our hearts, painfully aware of what the city has been, yearning for what the city can be and should be, gathered in a church building tragically known for the worst in the human heart, the malicious bombing that killed little girls in the midst of the civil rights tension of the 1960s. The former chief of police for Birmingham, an African-American woman, led us in the song, which itself seemed a remarkable window into what has changed in the city— no longer Bull Connor bullying his way through town, but the great-great granddaughter of slaves given the responsibility for the city’s safety. A hint of hope in every important way.

But from beginning to end, I was struck by the irony of history too, the ironies of providence written into the very song being sung in that place by those people. In the very room we were meeting was a glass case with a model of a slave ship, asking us to remember to remember what once was, the reality that every black person there was a descendent of someone who had been stolen away from an African home, chained to hundreds of others in the hold of a ship that made its way across the “Middle Passage” as the trip was called from Africa to America. Those who made it across the Atlantic were sold as slaves in the Savannah’s of these United States, those who didn’t were thrown overboard along the way, chattel as they are, disposable property as they were.

And as most everyone knows, John Newton, composer of “Amazing Grace,” was a slave ship captain. In our fantasies we imagine that he did the unimaginable and horrible before his conversion, “I once was blind but now I see,” and soon after he came to faith understood the wrong written into his work; and then urged his young friend William Wilberforce to stay in politics and work for the abolition of slavery. That would be a happier story. But from what we know from history, he kept at his slave-trading for years, continuing to captain ships full of slaves while on the top deck leading other officers in the study of Scripture— seemingly unable to connect his worship and his work, his beliefs with his behavior.

For a thousand complex reasons of the heart, like Newton, we are disposed to dualism. We choose incoherence rather than coherence, a fragmented worldview over a seamless way of life. For example, painfully so in this political season, we are first of all liberals or conservatives, Republicans or Democrats, our social and political ideologies shaping our identities; then we are good Baptists too, good Catholics too, good Methodists too, and on and on and on. When former presidential candidate Ben Carson famously said last week, defending another presidential hopeful’s reprehensible behavior, “Sometimes we have to put our Christian principles on pause to get the work done,” he reflected this disposition to dualism. I believe one thing, but the way I live requires something else altogether— and the spirit of realpolitik wins again, sons of Adam and daughters of Eve that we are.

What particularly struck me about the irony of singing Newton’s song while in the room with the slave ship was that it is a sober reminder that the work of thinking christianly is hard work. We do not come to it naturally, as ducks to water. Again, we are disposed to dualism, to carving up our consciences to allow us to believe one thing and behave as if another thing is true. “Did God really say?…. of course not!” is the temptation coursing its way through the human heart.

It was a long pilgrimage for Newton, perhaps 25 years, maybe longer. We do not have access to him now, of course, so we can only read what he wrote. While he stopped slave-trading some five years after his initial repentance, it was not until 30 years later that he made his first public statement, acknowledging his sorrow. “It will always be a subject of humiliating reflection to me, that I was once an active instrument in a business at which my heart now shudders.”

I don’t despise him for that. How could I possibly, so very clay-footed as I am? so very frail a man that I am? To learn to see clearly is a long work, and always a difficult work— disposed to dualism that we are. We are idolatrous people, twisting our hearts and world to make our choices for autonomy more comfortable in our conflicted consciences. We will do what we want to do when we want to do it, almost always.

That it took 30 years for Newton to begin to “see” is a strange grace to us. Blind as we are, hoping for sight as we do, most of the time the work of grace is more “slowly, slowly” as the Africans describe their experience of life in this wounded world. Grace, always amazing, “slowly, slowly” makes its way in and through us, giving us eyes to see that a good life is one marked by the holy coherence between what we believe and how we live, personally and publicly… in our worship as well as our work… where our vision of vocation threads its way through all that we think and say and do.

The Hebrews called this “avodah,” a wonderfully rich word that at one and same time means liturgy, labor, learning and life, a tapestry woven of everything in every way. That is the world we were meant to live in, and that is the world that someday will be. But now, in this very now-but-not yet moment of history, we stumble along, longing for a grace that connects our beliefs about the world with the way we live in the world. Over time that grace found Newton, transforming him heart and mind… “now I see.” May it be so for every one of us, blind as we are to our own disposition to dualism, hungry as we are for something more.