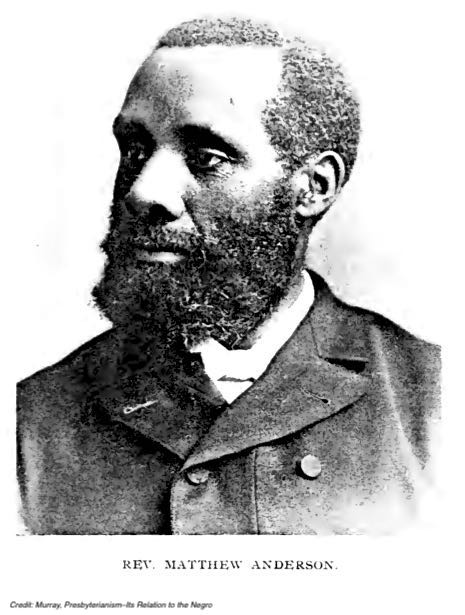

After taking the podium as the Presbyterian Church in America’s (PCA) first African-American Moderator on June 13, 2018, Rev. Dr. Irwyn Ince, Jr. gave a brief speech wherein he shared both his excitement to lead as well as his grief that there were so few models to inspire himself and other Black Presbyterians. “For most of my years in this church,” Ince said, “I have struggled to greet any court of our church with the phrase, ‘Fathers and brothers.’ Brothers? Yes. But fathers? No.” Things began to change, however, when Ince began learning about some of the courageous Black Presbyterians in American Presbyterianism’s history. His search led him to one such minister, Rev. Matthew Anderson, D.D., of the Berean Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia, whom he singled out in his address to his fellow commissioners at the Assembly.[1] What was it about the life of Matthew Anderson that proved to be so inspirational to Rev. Dr. Ince, and what can this African American minister continue to teach the Presbyterian church today? Matthew Anderson gave an indefatigable hope for the Presbyterian Church, demonstrated by both his passion for the spiritual and social uplift of African Americans and also his concern for raising the consciousness, empathy, and awareness of his fellow white brothers and sisters. My hope is that in telling Anderson’s story, Presbyterians today can find both encouragement and challenge from his life, and that his unwavering optimism would reenergize the efforts of the church today in its commitment to unity, diversity, and reconciliation.

Matthew Anderson’s Formative Years (1845-1878): Matthew Anderson was born to Mary (“Polly Croog”) and Timothy Anderson, Sr. on January 25, 1845, the eighth of fourteen sons and daughters. The Andersons resided on a family farm in Antrim, Pennsylvania (also known as Greencastle) in Franklin County. The Anderson family were free people,[2] with their status as free citizens tracing back to Matthew’s grandfather, Robert Anderson, a white Scots-Irish Presbyterian from Northern Ireland. According to the research of Bonnie A. Shockey, Robert worked on a slave ship that made continual trips between West Africa and America. After serving as a factor for an indefinite period, Robert decided to leave the slave trade behind him. On his final voyage, Robert became infatuated with a Black woman on board and proposed to her, promising her freedom in return for marriage. She agreed and the two found their way to Pennsylvania.[3]

The stories and experiences that Robert and his wife shared with his children may have served as inspiration for Timothy Anderson, Sr. to become an “engineer” on the Underground Railroad. Located about three miles north of the Mason-Dixon line, the Anderson farm became a haven for fugitive slaves looking to flee the South. In the autobiographical section of his book, Presbyterianism–Its Relation to the Negro, Matthew recalled that

Among the earliest impressions made upon our childish mind were the tales of horror about the South told by the fleeing fugitive as he lay in the secret enclosure of my father’s house where he was concealed.…We had heard much about the South, the country the people, the state of morals, the cotton fields, the rice swamps, the whipping posts, the slave pens, the cabins, the swarms of colored [sic] people and their wrongs.[4]

It would be through the formative impact of these interactions that Anderson and his siblings[5] would be inspired to become active themselves in the family business of the improvement of African American men and women.

Perhaps an even stronger formative component of Matthew’s upbringing was his religious faith. A fifth-generation Presbyterian,[6] Matthew grew up in a vibrant Christian home, with his father as an example of prayer and faithfulness. Anderson also recalled being catechized as a child and being regularly involved in the church as he grew up.[7] It would not be an understatement to suggest that it was the Anderson family’s robust practice of their faith that led Anderson to believe that Christianity in general, and Presbyterianism in particular, would be instrumental in the spiritual and social renewal of Black people.

This combination of Christian devotion and social activism would lead Matthew to pursue further education. At 18, Anderson left home to attend the Iberia School in Ohio, an institution with abolitionist sentiments. Matthew was determined to excel at Iberia, and he graduated three years later as the second of his class.[8] Shortly thereafter in 1869, four years after the end of the Civil War and the enactment of the Fourteenth Amendment, Anderson had a desire to put his education and missionary zeal into action, a desire that led him to become a teacher at a newly opened Presbyterian Freedman’s school in Salisbury, North Carolina.[9] Fully aware of his rights and privileges as a free citizen, Anderson stood his ground in the newly liberated South, refusing to cave into the pressures of the second-class structures that were beginning to take shape.[10]

The discrimination and the estate of African Americans which Anderson both experienced and observed in the South compelled him to acquire more training. In 1871 he returned to Oberlin College, where he completed his course of study in 1874. Immediately upon graduation, Matthew applied to Princeton Seminary, where he was accepted to begin his theological studies as a residential student that fall. His arrival to the seminary, however, was met with surprise and confusion. Dr. John McGill, who approved Anderson’s application, was shocked to discover that Matthew was a Black man. Upon learning this, Dr. McGill tried to walk back his promise to Anderson regarding on-campus housing, trying instead to direct him to an off-campus option. Anderson politely refused, insisting that Dr. McGill honor his word toward him that he would stay on the grounds of Princeton. Dr. McGill acquiesced and had the lumber room converted to a dormitory for Matthew. After a complaint from a white student about his deplorable living conditions, he was given an actual dorm room at the seminary. Matthew Anderson’s courage resulted in him becoming the first African American to board on-campus at Princeton Seminary.[11]

Aside from this episode, and similar ones,[12] Anderson was grateful for his education at Princeton. Studying under theologians Charles Hodge, James McCosh and other faculty, Matthew’s theology began to solidify and take a distinctly Presbyterian shape. Put through the same rigor and curriculum as his white peers, Anderson began to see the value of what Presbyterianism had to offer. He saw four benefits that Presbyterianism contained: the appeal to both one’s understanding and feelings, the doctrine of the perseverance of the saints, the governing structure of the church to curb vice and promote virtue, and the sound and life-giving teaching of the Word of God.[13] Anderson would go on to graduate Princeton in 1877, and after a three month engagement in New York working for the American Missionary Association,[14] he moved to New Haven to both pastor a church and take additional classes at Yale until 1879.

The first thirty-four years of Anderson’s life served to draw out two pillars that served as the foundation of his life’s work in Philadelphia. The first pillar was Anderson’s commitment to the improvement of his race. Growing up in the waning years of slavery and the Civil War and coming into his own at the dawn of Reconstruction, Anderson was familiar with the plight of African Americans and cultivated an understanding through his experience of what they would need to raise their status in a changing America and to thrive in a quickly urbanizing and industrializing society. The second pillar was the spiritual need of his brothers and sisters and his desire to share the gospel with them. Anderson firmly believed that any social uplift on the part of the African American community must be accompanied by spiritual renewal for it to be maintained. It seemed that Matthew Anderson’s background and education–as a free, biracial, Princeton-educated, Presbyterian–uniquely suited him to be used by God in Philadelphia.

Matthew Anderson as Presbyterian Clergyman (1879-1928): After two years of ministering to a “fossilized” church in New Haven, Matthew Anderson began to sense that God was leading him elsewhere, but he was uncertain of what that next step looked like.[15] He contemplated engaging in missionary work in the Cumberland Valley among the Freedmen, and as he weighed these things in his mind, he decided to travel home to Greencastle, stopping in Philadelphia on the way.[16] Little did Anderson know that this pit stop in Philadelphia would become the epicenter of his ministry.

In 1789 in Philadelphia, Anderson met Rev. Dr. John B. Reeve, pastor of the Lombard Street Central Presbyterian Church (LSCPC), who presented him with an interesting opportunity. A year previously, LSCPC began a new work in the northwestern section of Philadelphia called the Gloucester Presbyterian Mission. The Mission struggled to gain traction in the area due to turnover of its ministers–going through three in the first year alone. Dr. Reeve, upon learning that Anderson was looking to enter the mission field, challenged him to take on the Gloucester Mission, claiming there was no better mission field than that. After thoroughly examining the field, Anderson agreed. He took over the Gloucester Mission on October 4, 1879, and on June 11, 1880, the Berean Presbyterian Church was organized.[17]

As he assessed the situation in Philadelphia, Anderson noticed three obstacles to fruitfulness in this work. The first was finances–there were no funds given by the Presbytery, and the people whom the Gloucester Mission served were poor and could not sustain the work themselves. This obstacle was surmounted through Matthew’s tireless fundraising efforts.[18] Second was the apathy of the Presbytery. Anderson recorded that “mission work had been so long neglected among the colored [sic] people that the Presbyteries had almost lost sight of them, and they were very ignorant as to their real wants and condition.”[19] This barrier was a continual struggle for Anderson, and he sought to constantly raise the consciousness of his fellow ministers through committed involvement in the Presbytery. The third obstacle was the apathy of the African American community. While there was a demand for new churches in northwest Philadelphia (there was only one Methodist mission for the 6,000 residents),[20] Anderson saw that the people:

…were for the most part indifferent, if anything prejudiced, not so much towards the establishment of this particular church, but towards the Presbyterian Church generally, and this prejudice was inherited, being associated in their minds with the church that encouraged slavery, also, as being cold, aristocratic, pharisaical, and which had no use for the Negro [sic] more than to use him as a servant. This spirit would have to be overcome before there would be any marked success, as well as their spirit of general indifference towards all church work, resulting largely from the spirit of neglect and indifference, which would have to be grappled with before the banner of success could be unfurled.[21]

In other words, the apathy of the Presbyterian church created a callousness among Black people, and Anderson would have to work even harder to overcome their skepticism and win their trust.

This is precisely what Matthew Anderson set out to do. For the next forty-eight years until his death in 1928, Matthew faithfully served as the senior pastor of Berean Presbyterian Church. The church’s doors were open every Sunday and held multiple services each week, with Anderson being the primary preacher and teacher. The church also offered a Sabbath School, offering biblical education to 150 people. Anderson also used the church building as a hub for other initiatives that he referred to as “the Berean enterprise.” Despite having such a long ministry in Philadelphia, very few of Anderson’s sermons are extant today. However, snippets of his sermons have been preserved by local periodicals. What the newspapers record of Anderson’s preaching revealed that he was a preacher of God’s grace in Christ. In one sermon, preached on Exodus 14:15, Anderson connected the work of God in the Old Testament to the work of Christ in the New, saying, “Just as God interceded in behalf of His people of old, so will He do now, and will guide them not with a pillar of cloud or of fire, but by a personal Christ, the risen Saviour of mankind, to the mercy seat around which every one that will may bow.”[22]

In addition to his efforts as the senior pastor of Berean, Anderson also strived to be an agent of change at the denominational level. This can be seen in two instances–the union with the Cumberland Presbyterian Church in 1906 and the Freedman’s Board in 1916.[23] The Cumberland Church, which had split from the Presbyterian Church in 1810, sought to be reunited with the mother church. The process of union began in 1903 with a committee tasked to study the boundaries of the presbyteries, and at the behest of the Cumberland Church, they pushed for the creation of overlapping, segregated judicatories. In other words, the Cumberland Church wanted race-based presbyteries as a condition of their reunion.

This demand of the Cumberland Church created a tension within the Presbyterian Church. The choice that now stood before the presbyteries was to either receive the Cumberland Church at the expense of racial equality or to reject reunion (and miss the opportunity for a “united” church) based on the principles of racial equality and dignity. On the side of rejection stood Matthew Anderson, Francis Grimké and others who spoke up and advocated for the northern church to stand for its principles. Grimké pointed out that Presbyterians in the north had been attractive to the African American community precisely because it was not a segregated church.[24] Anderson spoke up as well. In an article in The Philadelphia Inquirer, he asked, “Is it not time to consider seriously whether the Presbyterian Church is not surrendering principle for worldly power, pandering to a wicked color prejudice in order to bring about church union at the sacrifice of Christian union?”[25] Anderson, moreover, in a tone that was less polarizing than Grimké’s, also appealed to white ministers saying that what his people desired in this matter was not social equality per se, but ecclesial equality. Anderson’s diplomatic distinction in this instance was not to belittle or relegate his own race but rather to help white minsters differentiate the rights of African American people in general to their rights in this particular issue. In other words, Anderson hoped to show them that their vote on this matter was not for equality in every arena that white people had (though Anderson believed in that equality), but equality within the courts of the church.

Anderson’s diplomacy, however, would not prevail. As Murray notes, the ingrained sentiments of white people toward Black people–compounded by the “separate but equal” precedent set by the Supreme Court in 1896–led the Presbyterian church “to sacrifice the principle of racial equality on the altar of church union.”[26] The Cumberland Church was received into the Presbyterian Church at the General Assembly in Des Moines, Iowa, in 1906.[27] While Anderson would fail in this endeavor, his effort stands out as a prophetic critique of the church in his day.

The second way Anderson sought to elevate the status of Black people in the denomination was his push to merge the Freedmen’s Board with the Home Mission Board.[28] The occasion for this action was a desire by the Freedman’s Board to extend its works in the northern states and to assume the works among the African American community which were overseen by the Home Mission Board. Anderson spoke out against this initiative on the grounds that there should not be any distinction between Black mission works and white ones, and that if northern works were turned over to the Freedmen’s Board, they would inevitably be underfunded. Anderson countered the proposal with an overture of his own, which the Philadelphia Presbytery submitted to the General Assembly in 1916. This overture called for the merging of the two boards. In a pamphlet that Anderson distributed, he wrote:

I express the unanimous sentiment of the ministry and the intelligent laity of the colored [sic] Presbyterians in the north when I say that we do not want any special ecclesiastical legislation for our churches, nor special Boards for their supervision and direction; we must stand, having the same rights and privileges, absolutely the same status, if we would be Presbyterians. For this reason, therefore, we are not willing to be placed arbitrarily under the Freedmen’s Board or any other Board gotten up specially to manage colored [sic] work.[29]

In his correspondence with Francis Grimké, Anderson also notes how he labored to ensure his overture made it to the floor of the Assembly. He also described how the Freedmen’s Board fought the overture seeking to defeat it, and to Anderson’s dismay, Overture 33 did not make it out of the Committee. The overture was defeated by a slight majority.[30] As in the merger with the Cumberland Church, Anderson was not victorious in changing the denominational sentiments toward the African American community, but his persistence in fighting for equality and dignity would endure for future generations.

The Berean Enterprise: Matthew Anderson as Social Reformer: Not only did Matthew Anderson labor tirelessly in the spiritual renewal of his people, he also expended great effort in their social uplift as well. Anderson recognized that for African Americans to flourish in America, they needed to attain the means to become profitable citizens as well as securing their rights as equals under the law. As with his ministry in the church, Anderson’s work as a social reformer had both local and national emphases, locally with the Berean enterprise and nationally with his advocacy for equality.

At the local level, Anderson helped manufacture an ecosystem that was oriented toward the holistic development of Black people. In addition to laying the cornerstone that was the Berean Presbyterian Church, Anderson built many other institutions. The first to emerge was the Berean Kindergarten in 1884, the first school of its kind for Black children in Philadelphia. The school was self-sustaining from the start and was so effective that the city of Philadelphia took oversight of it and supplied it with teachers. The Berean Building and Loan Association, also organized in 1884, had as its goal to help African American families buy and own their own homes. Anderson saw home ownership as integral to the flourishing of Black people, and the Building and Loan Association helped over 300 families buy and secure their homes. The Association had an integrated board–another innovation–and it continued to be financially stable, even successfully weathering the Great Depression in 1929.[31] A medical dispensary, run by Anderson’s first wife, Dr. Caroline Anderson, opened in the church basement in 1890.[32] In 1899, Anderson organized and opened the Berean Manual Training and Industrial School, a trade school that sought to educate and equip people with the skills to earn a living in the industrializing northern cities.[33] And in 1894, the Andersons purchased a cottage in Point Pleasant, New Jersey, for Black families to use as a safe vacation destination.[34] On top of all these institutions were the numerous community societies organized by Berean and its members, such as the Boys Cadets and a chapter of the Y.W.C.A. If the Berean Presbyterian Church was the warp of Anderson’s tapestry for the African American community’s flourishing and development, the institutions of the Berean enterprise were its woof. So thorough and comprehensive was Anderson’s work in Philadelphia that W.E.B. DuBois concluded that there was “probably no other church in the city…[that] is doing so much for the social betterment of the Negro [sic].”[35]

Beyond Anderson’s actions at the local level, he was also quite active on the national–and international[36]–stage with his advocacy for Black people. Anderson gave regular talks on sociological trends in America and the Black community, and he would champion their dignity at educational conferences and in thinktank environments. Not only would Anderson draw attention to opportunities for advancement, he would also call out injustice and plead for change. Anderson gave talks on topics ranging from lynching,[37] brutality,[38] financial inequality[39] and restitution,[40]race riots,[41] and denouncing the activity of white supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan.[42] He would share the stage with other advocates like DuBois and Grimké in order to help shift the attitudes of white America toward African Americans.[43] While his voice would change little in his lifetime, Anderson’s efforts undoubtedly planted seeds for future participants in the Civil Rights Movement.

In the life of Matthew Anderson, we see a man whose love for God and his neighbor compelled him to kingdom building and institution building, to gospel proclamation and advocacy for the least of these. In his formative years and in his dual ministry as a pastor and social reformer, Anderson endeavored to not only teach people that Jesus loved them, but to demonstrate that love tangibly in their lives.

Why is Anderson’s story worth retelling today? After all, it story is easy not to tell, since many of his writings are buried in elite university library shelves or lost to obscurity. But it is worth doing the work to listen. If we fail to listen to these powerful but quiet voices, we are doomed to repeat history and will persist in our errors. We have much to gain from taking the time to learn from those Black Presbyterians who have gone before us, men who through their character, words, and actions have beckoned the church to biblical faithfulness and away from cultural captivity. Anderson himself must have the final words. In Presbyterianism–Its Relation to the Negro, he presents two challenges to the Presbyterian Church that are still relevant now as they were then. Anderson lamented, “There is a great deal of pity, but very little love and respect for the Negro [sic].…They know all about their faults…but they cannot tell you anything about their virtues, their struggles against almost insurmountable obstacles and their triumphs.”[44] The first challenge for the church today–especially the white-majority church–is to move from pity to genuine love for our black and brown image bearers. Can we adopt a sincere curiosity to learn about the cares and concerns of Black people and commit to share not just the gospel but our resources, even our very lives for their good and flourishing?

The second challenge that remains for the church today, according to Anderson, is not just love, but fellowship:

Let the Presbyterian Church make the Negro [sic] feel that he is wanted, and not merely tolerated, let it throw away its patriotism and receive him as a friend and brother and it will have in him a friend and brother and it will have in him a staunch friend and defender, one who will unbare his bronzed bosom to the foes of right and truth.[45]

Will the church do what it takes to move beyond toleration to friendship, from giving them a voice at the table to a seat at the table? What are some practical ways that denominational leadership can create more room for those voices that have for so long been excluded from our ecclesiology? Anderson promises that when we create space, we will all be the better for it.

Matthew Anderson viewed the whole of ministry as a mosaic–a combination of unflattering, seemingly useless shards that had been polished and arranged by the Holy Spirit into a beautiful work of art for the glory of God and the good of his people.[46] He saw no worthless people. He refused to dehumanize friend and foe. He believed no one was beyond redemption. This same hope is what Anderson still holds out to the Church today. Will we take Anderson’s challenge and seek to recognize the image of God in all people and seek their spiritual and social welfare–to love God with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength, and our neighbor as ourselves? I hope so.

[1] “Wednesday PM General Assembly Business,” Presbyterian Church in America (PCA), accessed December 12, 2020, https://livestream.com/accounts/8521918/events/8226818/videos/176322911.

[2] With regard to terminology, I preserve the archaic terms “Negro” and “colored” when quoting original sources. Everywhere else, I will use the term “Black” or “African American.”

[3] “Anderson Family of Antrim Township,” Bonnie A. Shockey, accessed December 12, 2020, https://greencastlemuseum.org/anderson-history.

[4] Matthew Anderson, Presbyterianism–Its Relation to the Negro (Philadelphia, PA: J.M. White, 1897), 155-156. The abbreviation PRNwill be used to refer to this volume going forward.

[5] Shockey, “Anderson Family.” Shockey notes that at least one of Matthew’s siblings, Moses Anderson, also became involved as an activist for the Black community’s improvement and civil rights; see Valley of the Shadow, “Address of Penna. State Equal Rights League,” Franklin Repository, June 5, 1867.

[6] “The Whole Gospel for the Whole Community,” Presbyterian Historical Society, accessed December 12, 2020, https://www.history.pcusa.org/blog/2016/02/whole-gospel-whole-community-legacy-matthew-anderson.

[7] Matthew Anderson, “Fifty Years Ago,” Greencastle Echo-Pilot, March 25, 1905. Quoted in Shockey, “Anderson Family.”

[8] Anderson, PRN, 141-143.

[9] Joseph R. Washington Jr., Race and Religion in Mid-nineteenth Century America, vol 1 (Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen Press, 1988), 616.

[10] Anderson, PRN, 156-161.

[11] Ibid., 165-168.

[12] Ibid., 173-176.

[13] Ibid., 122-123.

[14] Ibid., 177.

[15] Ibid., 189.

[16] Ibid., 19.

[17] Ibid., 38. C. James Trotman also notes that the name “Berean” for Anderson reflects his two life goals for spiritual and social renewal of black people. One the one hand, Berean is a spiritual reference (Ac. 17:11); on the other, Anderson labored as an evangelist in Berea, Ohio in 1872. See “Anderson, Matthew (1845-1928),” American National Biography, accessed December 12, 2020.

[18] Anderson, PRN, 101-108.

[19] Ibid., 13.

[20] Ibid., 28.

[21] Ibid., 29.

[22] The Times, “Christians, Go Forward,” March 12, 1894.

[23] Andrew E. Murray, Presbyterians and the Negro (Philadelphia, PA: Presbyterian Historical Society, 1966), 196-202; 208-210. In addition to these two, another notable contribution by Anderson in this area was the co-founding of the African American Presbyterian Council in 1984.

[24] Ibid., 200.

[25] Matthew Anderson, “Jim Crow Presbyteries,” The Philadelphia Inquirer February 24, 1905, accessed December 12, 2020.

[26] Murray, Presbyterians and the Negro, 200-201.

[27] There is a jarring juxtaposition of Anderson and the Cumberland reunion on the front page of The Des Moines Register, May 25, 1906. Two headlines stand out. The first and most prominent one is “Presbyterian Union Is Now Accomplished,” and it describes the union of the two denominations. The second headline on the front page is “Negro Is Excluded by Princeton Men,” which is about Anderson being barred from attending a dinner for Princeton Seminary alumni. Taken together, the front page reveals the hypocrisy of the Presbyterian Church and their attitudes toward Black people. See graphic of the front page in appendix.

[28] See C. James Trotman, “Matthew Anderson: Black Pastor, Churchman, and Social Reformer,” American Presbyterians 66, no. 1 (1988): 18-19; Murray, Presbyterians and the Negro, 208-210; and Carter G. Woodson, ed., The Works of Francis J. Grimké, vol. 4 (Washington, D.C.: The Associated Publishers, Inc., 1942), 165-169.

[29] Matthew Anderson, “The Presbyterian Church Must Stand by its Doctrinal Standards as to Race,” p. 2. Quoted in Trotman, “Matthew Anderson,” 19.

[30] Murray notes that the matter was later referred to the General Assembly the following year, in 1917. However, with the onset of World War I, the action was postponed. See Presbyterians and the Negro, 210.

[31] Trotman, “Anderson, Matthew.”

[32] Caroline is a giant in her own right. The daughter of the prominent abolitionist William Still and one of the first African American graduates from a Pennsylvania medical school, she married Matthew Anderson on August 17, 1880.

[33] Matthew Anderson, “The Berean School of Philadelphia and the Industrial Efficiency of the Negro,” Industrial Education 33, no. 1 (1909): 111-118. See also Matthew Anderson, The German Gymnasia Versus Negro Education (Princeton, NJ: publisher unknown), 1916.

[34] The purchase of this cottage caused national scandal, appearing in multiple newspapers across the country. For one example, see “Negro Neighbor Casts a Shadow,” Fort Scott Daily Tribune June 19, 1908.

[35] W.E.B. DuBois, The Philadelphia Negro (Princeton, NJ: publisher unknown, 1916), 217.

[36] “Philadelphians Go to Rouen,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, September 20, 1903.

[37] The Times, May 14, 1899, page 7.

[38] “Blames Rev. Mr. Elwood,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, June 25, 1903.

[39] “Negro Financiers,” The Colored American, January 24, 1903.

[40] “$275,000,000 Taxes Paid by Negroes,” The Topics, June 29, 1895.

[41] “Race Riot Caused by a Press Agent,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, October 23, 1906.

[42] “A Call to Action,” The Broad Ax, November 10, 1906.

[43] “Social Problem Topic Scheduled for Debate,” Evening Star, December 26, 1909.

[44] Anderson, PRN, 217.

[45] Ibid., 67.

[46] Ibid., 260.

SOURCES

Anderson, Matthew. “The Berean School of Philadelphia and the Industrial Efficiency of the

Negro.” Industrial Education 33, no. 1 (1909): 111-118.

_____. The German Gymnasia Versus Negro Education. Princeton, NJ: publisher unknown,

1916.

_____. Presbyterianism: Its Relation to the Negro. Philadelphia, PA: J.M. White, 1897.

DuBois, W.E.B. The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study. New York, NY: Schoken Books,

1967.

Murray, Andrew E. Presbyterians and the Negro–A History. Philadelphia, PA: Presbyterian

Historical Society, 1966.

Presbyterian Church in America (PCA). “Wednesday PM General Assembly Business.” Accessed December 12, 2020. https://livestream.com/accounts/8521918/events/8226818/videos/176322911.

Presbyterian Historical Society. “The Whole Gospel for the Whole Community: The Legacy of Matthew Anderson.” Accessed December 12, 2020. https://www.history.pcusa.org/blog/2016/02/whole-gospel-whole-community-legacy-matthew-anderson.

Shockey, Bonnie A. “Anderson Family of Antrim Township.” Accessed December 12, 2020. https://greencastlemuseum.org/anderson-history.

Trotman, C. James. “Anderson, Matthew (1845-1928), Presbyterian pastor, educator, and social

reformer.” American National Biography. 1 Feb. 2000; Accessed 12 Dec. 2020.

https://www.anb.org/view/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.001.0001/anb-9780198606697-e-1501110.

_____. “Matthew Anderson: Black Pastor, Churchman, and Social Reformer.” American

Presbyterians 66, no. 1 (1988): 11-21. Accessed December 12, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23330763.

Washington, Jr., Joseph R. Race and Religion in Mid-nineteenth Century America, 1850-1877:

Protestant Parochial Philanthropists. Volume 1. Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen

Press, 1988.

Woodson, Carter G., ed. The Works of Francis J. Grimké. Volume 4. Washington, D.C.: The

Associated Publishers, Inc., 1942.

PERIODICALS CITED

The following periodicals were accessed on Newspapers.com on December 12, 2020:

The Broad Ax. Salt Lake City, UT.

The Colored American. Washington, D.C.

The Des Moines Register. Des Moines, IA.

Evening Star. Washington, D.C.

Fort Scott Daily Tribune. Fort Scott, KS.

The Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, PA.

The Times. Philadelphia, PA.

The Topics. Kansas City, KS.

Other:

Valley of the Shadow. “Address of the Penna. State Equal Rights League.” Franklin Repository,

June 5, 1867. Accessed December 12, 2020.

https://valley.lib.virginia.edu/news/fr1867/pa.fr.fr.1867.06.05.xml#02.