Hark! the herald angels sing,

“Glory to the newborn King!”

This past weekend I was in Houston, the vastness of Texas constrained in one metropolis that goes on and on… together with good people from all over America and the world. For several days we had deep conversations about things that matter to all of us—whether from Santa Monica or Seattle, Dallas or Durham, from Africa or Asia, each one eager to think more carefully and completely about the meaning of vocation in and for the world.

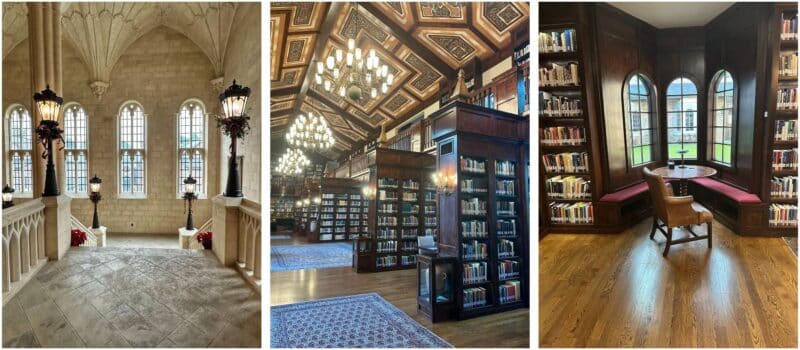

We met at the Lanier Theological Library and Learning Center, born of the vision of Mark Lanier, a Houston attorney who believes that the church in the world needs access to more theological resources, and has built an Oxford University-inspired campus that intends to make that possible. With its beautifully-imagined buildings it is a great surprise to all who make their way through its gates, with Houston all-around and yet, Oxfordshire and the Cotswalds, too.

Photos from the Lanier Theological Library, Houston, Texas

An annual retreat sponsored by a Foundation for Theological Education, for PhD students with their professors and deans from throughout the U.S. and the U.K., its purpose is to offer theological grist for more faithful work in and for the world. Asked to reflect aloud for all, I gave plenary addresses on ideas that course their way through my own calling, the meaning of vocation and the idea of the proximate.

What is vocation? And the vocation that grows out of theological study? How do we understand it? To whom and what do we belong? To the “guild” or to the church and the world, which is a harder question than it might seem? And what does common grace for the common good mean here? How do we avoid the disposition to dualism that plagues the academy and the church all over the world? And then, what is the proximate? What does it mean to honestly live in the now-but-not-yet of history? Between “all things have been made new” and “even the creation groans”? Can we find any true coherence between metanarrative and narrative, between what we believe about all of life, and the way we live our own lives? Between what we think about all of reality, and the reality of our finite and frail experience? Is something that is more beautiful, more honest, more just, more merciful, more true, worthy of our lives? Can it be a signpost that something matters, even if it is not everything? We spent several hours over the days on this, thinking together, asking and answering questions.

Because I am always interested in where I am and who I am with—“even your own poets have said”—I lingered over the city of Houston and Texas-born songs and stories… from the opening scene in the Houston-filmed, Reality Bites of a generation ago, to Texas’ troubadour extraordinaire, Willie Nelson, whose songs are for the ages, onto its most gifted filmmakers, Horton Foote and Terrence Malick, reflecting on their best work, wanting to situate us among the people and place that the Lone Star State is (perhaps too) proud to be.

If my thinking was situated in the Texas of here-and-now, it was also remembering that wherever we are, whoever we are, every one of us knows what it is to long for something that seems beyond us, and yet sometimes seems almost everything to us. If honest, even painfully honest, all of us know the ache of misdirected longings, of loves that become disordered, disordering our lives. As the iconic song of Houston once put it, “I was looking for love in all the wrong places”—we do and we will, sons of Adam and daughters of Eve, again and again. And Augustinian that I am, my deepest beliefs about history and human nature formed by this African saint, I never get far from his understanding of who we are, and why we are, of what the world is, and what it isn’t. Threaded through all, for him and therefore for me, is the insight that it is our longings that tell the truest story about us—what do we long for, and why?

But given that it is Christmastide, it was also important to begin and end with two of the best stories all of us know, both born of vocations lost and found A Christmas Carol and It’s a Wonderful Life, in the days of December we were, paying attention to the questions of Christmas, and the hope of Advent.

Are we lost in the cosmos? Is this a silent planet? Is our despair the last word, or is there a word from God in heaven about what it means to live on the earth? Or has God remembered us, even in our forlornness? Has God in fact come to earth?

Bah, humbug! Bah, humbug! Bah, humbug! Everyone everywhere knows that this is the story of Ebenezer Scrooge, and a story of vocation it is, the story of a life from its first years to its last years, of boyhood loves and longings, of youthful ambitions and hopes, followed by the settling-in years where we all become who we will be, for blessing and for curse. And then, for him and for us, year after long year, we live into the reality that both body and soul keep score, very painfully so for Mr. Scrooge.

Bah, humbug! Bah, humbug! Bah, humbug! Everyone everywhere knows that this is the story of Ebenezer Scrooge, and a story of vocation it is, the story of a life from its first years to its last years, of boyhood loves and longings, of youthful ambitions and hopes, followed by the settling-in years where we all become who we will be, for blessing and for curse. And then, for him and for us, year after long year, we live into the reality that both body and soul keep score, very painfully so for Mr. Scrooge.

But the questions at the heart of his life are the questions that run through every life. Who am I? Why am I? What will I do with my life? Then in the dark, long night of Ebenezer’s soul, on the very precipice of eternity, he is given the grace of looking into the way he has answered those questions—and you know the rest of the story as well as you know your own life.

The questions which form this story of a life, form the story of every life. Theologically-rooted as they are, they are also the most human questions of all. Sons of Adam and daughters of Eve the world over wake up in the morning living into their answers, sometimes very attentively and thoughtfully, and perhaps more often than not simply trying to keep alive one more day, not paying much attention at all. But they are our questions.

The other story is known to us as It’s a Wonderful Life, which of course does not feel that way to George Bailey, who in his anguish cries out to heaven, hoping that there is a God who will hear. And it too is a story of vocation, lost and found, and wonderfully—very good word that it is—found again.

But it is also a story of making peace with the proximate. Young George was full of dreams about his life, about what he would do, and where he would go. Simply said, he expected everything to come true! Slowly by slowly, he came to see that that was not going to happen. His travel, his education, even his honeymoon, then his house, and finally his work—nothing turned out to be what he imagined. But this is the story of someone who got something, if not everything. And that he came to see his life as “wonderful” is only because he finally had eyes to see the Story of Stories for what it was, and his story for what it was…crying out to heaven, and by surprising grace, heaven hearing him.

At the film’s end there is a mysterious, merciful reordering of his life and his loves, seeing that the most important things had to become the most important things. In the grand moment when George comes home, overwhelmed by his family’s love and his community’s affection, we know that he knows that he has not been forgotten, by God or the world—which for this story’s sake, makes his life “a wonderful life.”

Through the long weekend, from morning to night, I was with women and men who are giving away their lives for what matters most, hoping for something more, for deeper graces and deeper truths, willing to wrestle with heart and mind over the question of vocation and the work of God in the world, the very wounded world it is. As plainly as can be said, we thought and thought again over these words, a credo for all those who long for their lives to be woven into the meaning of history, not unlike the heroes of our stories here: vocation is integral, not incidental, to the missio Dei. Yes, and yes, in your life and mine.

And yes too, I even played Willie Nelson’s version of “Hark, the Herald Angels Sing,” sensing that it made more sense for those of us gathered in Houston, Texas to listen to the poet-laureate of the Lone Star State as we pondered anew the meaning of our lives and learning, remembering to remember that the meaning of Christmas makes its way in and through our lives over the years of our lives—and poignantly but profoundly, that Ebenezer Scrooge and George Bailey have gone before us.