“He bent over all that groaned… the universe appeared to him an immense malady; he felt fever everywhere; he heard the sound of suffering all around him; and without trying to solve the enigma, he sought to heal the wound.”

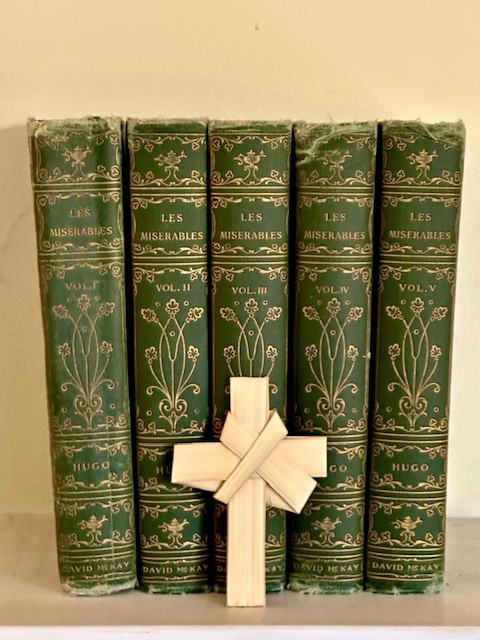

I read these words, again and again, year after year, wondering what they mean, wondering how one comes to see and hear the world like this? They are the deeper story of “Les Miserables,” which as I wrote a few days ago has been a Lenten reading for me again, particularly the first book, “The Just Man,” which is about Bishop Bienvenu. Anyone who has seen the play remembers this unusual man, marked by such unusual grace, and we wonder, “Why?” and “How?” Why are you the way you are? How did you become the way you are?

Even after Lent, the book still echoes within me, and this week I have been thinking about the words above. They come from the chapter that immediately precedes the entrance of Jean Valjean into the story, and so decades into the life of the bishop, which as Hugo tells the tale, is a wonderfully rich account of the pilgrimage of his life. Because it is true that at “crucial moments of choice, most of the business of choosing is already over,” it must be that the bishop had formed habits of heart that gave him eyes to see “the miserables,” those who groan and suffer in this life—and that he understands his own vocation as written into what he sees.

There is enough sorrow to go around; more often than not it is right next to the doors of our hearts, and if we are paying attention there is more from every corner of the earth. Every day of my life I hear one more story of disappointment and disease, of grief and sadness, of losses that bring deep ache, of longings that are not easily answered. Whether in a note, a letter, a phone call, a conversation, or the news of the day, I breathe as deeply as I can, knowing that in some way on some level I will have to respond; and not only that I have to, but that I want to—believing that there is a place of mystery deep inside where duty and desire touch, profoundly influencing each other, finally becoming the very same, even if proximately.

There is a weight to love, always, as Augustine has taught us, in seeing ourselves implicated for love’s sake. For that reason it is a grace to read that the bishop did not see himself able to “solve the enigma,” to make the problem go away—rather, “he sought to heal the wound.” What that means, how that happens, is finally beyond us. There are no books to read, there are no degrees to attain that prepare us for that; and while I do not disdain what can be learned from pages and programs, the kind of learning that transforms us is always over-the-shoulder and through-the-heart— and most deeply of all, of course, it is grace, surprising grace.

In a strange way the bishop has become my teacher, because for years I have been listening and learning to him. While sometimes I sigh in reading his story one more year, feeling far from the virtues that mark his life, he inspires me because he instructs me, with rare humility pointing a way forward, inviting me to come and see his own imitation of Christ.

For whatever mysterious reasons of providence that are played out in my own being, I know that I hear the groaning, that I see the malady, that I see the suffering, that I am stilled before the enigma of it all, and that I long to respond, hoping and hoping that wounds will be healed—even knowing that at best, in this now-but-not-yet time of history, the healing that is possible is not everything.

Wounds wound, and there are scars. But there is healing that is honest and true, and even if it is not everything, it is something.