“I know Mr. Rogers, but does Mr. Rogers know me?”

A long time ago one of our little ones asked us this question, perplexed by the technology of television. We smiled as we did our best to wade through the epistemological challenges of being human in the modern world— not laboring very long over them, I confess, as we mostly wanted to honor the very good question it was. How can I “know” someone, if they don’t “know” me?

Knowing about is not the same thing as knowing. I can know about the city of Vancouver, without ever knowing what it means to live in the city of Vancouver. I can know about oceans, without knowing what it feels like to swim an ocean. I can know about horses, without ever having ridden a horse. I can know about the idea of marriage, without ever knowing the meaning of marriage.

And as J.I. Packer has written for the ages, one can know about God without knowing God.

In the years when I was sorting through what I was going to believe about the world and why, I read Packer’s “Knowing God,” in its first pages struck by the distinction that he made. The more I thought about it, the more convinced I was that I had spent a lifetime so far knowing about God but had not really given much attention to knowing God. Now years later I have come to see the difference and the difference it makes.

One of God’s very good gifts to me along the way has been a friendship with Dr. Packer, many times in many places having conversations with him about many things. We have had him in our home, watching him come down to our children on his haunches, speaking personally to each one by name, saying very simply, “The most important thing in your whole life is that you come to know God.” I have driven miles with him, taking him here and there, the car full of my questions, him patiently and wisely answering. I have invited him to speak in different settings, trusting that he would do very well, wonderfully well, addressing the audiences of my world. I have met him in airports, surprised to see him making his way through the terminal, stopping to catch up. And I have even had the great gift of speaking alongside him, sharing the lectures of a conference with a man who has been my great teacher.

When I was writing the “Visions of Vocation,” aware that the question, “Can we know the world, and still love it?” would be threaded through from beginning to end, I had a place for more from Packer, long remembering his insight in the chapter, “Knowing and Being Known,” when he wrote that “God knew the worst about us when he chose to love us” and therefore that we could never surprise him with our waywardness, with the shames that shame us. “No discovery now can disillusion him about us” were the clear words from Packer, and they are written on my heart.

The book is of course about vocation, about who we are and why we are, about what we do in the world with the hopes that are ours, with the longings that are ours, with the gifts that are ours, with the responsibilities that are ours. Yes, all of that embedded in the deeper reality that vocation is always our response to the question, “What will we do with what we know?”

But frail, finite human beings that we are, what we know often feels as if it is too much. In the Information Age when we have 24/7 access to knowing about everyone everywhere, we are overwhelmed, sometimes even numbed— and that is a problem. But lest we imagine that our age is so different, even the Stoics and Cynics of thousands of years ago thought it was “too much,” their distinctive responses being different ways of suppressing what they knew about the world, protecting their hearts from the implications of the primordial and perennial question, “What will we do with what we know?” Given the weight of the world, I understand why we suppress, and why we protect. Most of the time the world is too wounded, and we are too.

But my question remains. “Can we know the world, and still love the world?” I have come to believe that is the hardest of all the questions. Nothing is as costly as grace, and that is what it is to live into that question, taking its meaning into our hearts. Very personally and very publicly, to know and to still love is the heart of the truest vocation, in imitation of Christ as it must be— at work and at play, in our homes and in our cities, from the very nearest neighbor to the very furthest friend, across the whole of life in every area of life.

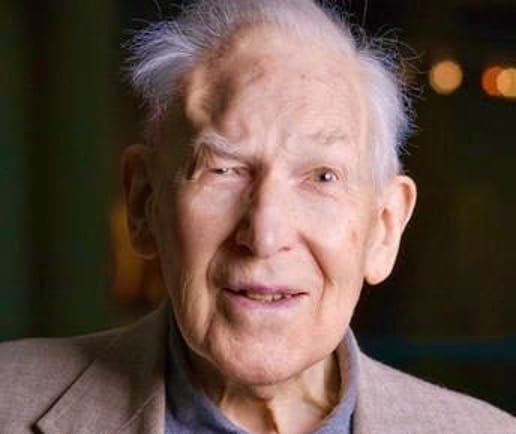

Photo of J.I. Packer on 27 October 2018 in the Rare Books Reading Room at Regent College, reflecting on his long love of John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, with a very early edition of the book beside him. His kind smile is a window into his heart, the great scholar and good man that he was— who has now crossed the River of Death and entered the Celestial City.

“Athos uttered a cry of terrified tenderness.”

Sometimes we read a story and think, “That’s exactly right.” We are sure the author sees the same world we do, lives in the same world we do. Long persuaded as I am that Walker Percy’s insight is perennially and universally true—“Bad books always lie; they lie most of all about the human condition” –I always read with this question in mind: is this true to who we are as human beings?

The few words above are from “The Man in the Iron Mask” by Alexandre Dumas, who also authored “The Count of Monte Cristo” and “The Three Musketeers.” In long drives across the miles of America the last few summers, Meg and I have listened to these stories, this year taking up “the iron mask.” Historical fiction as it is, Dumas imagined a tale where there were twin brothers born to the king and queen of France. Because of royal intrigue, only one birth was announced, and Louis XIV eventually became the Sun King of Versailles. His identical twin, the story offers, was kept away from any public life, and in early adulthood was imprisoned. Much more could be said.

Dumas’ “three musketeers” are written into the story, and in fact it is their relationships and responsibilities that are the heart of the novel. They are d’Artagnan, whose life is the centerpiece, and his friends, Aramis, Porthos, and Athos. Of course it is swashbuckling—how could it not be? But the novels also explore the great questions of life for Everyman and Everywoman: friendship, ambition, grief, pride, selflessness, and more. They are classics for good reasons.

But “a cry of terrified tenderness”? It is the lament of Athos at the death of his son, crying out as only a father can against heaven and history at his grievous loss.

Not being him, I understand him. We live in the same world and have the same feelings about the world. His heart is my heart, his hopes are my hopes, his sorrows are my sorrows. In Dumas’ distinctive way—a million miles from Shakespeare and Dickens, from Percy and Berry–his story tells the truth about the human condition. Living the life I live, I too cry out with terrified tenderness, especially being a father like Athos.

For years now I have answered the innocent question, “So how are you—and how are your kids?” with the simple, and yet deep-as-my-heart allows, “I wake in the morning with my children in my throat.” I suppose I could just say, “Fine—and you?” But that isn’t true for me, or anyone else. It is not true for and about the human condition. We are not fine, after all, because the shame and sorrow of self-knowledge runs through everyone’s life, day after day, with complexity and heartache.

Having spent a few days with J.I. Packer several weeks ago, speaking alongside him at the Laity Lodge in Texas—which, given his formative influence on me for most of my life, was a great gift —I was impressed again with his honesty about the things that matter most. One of the reasons that people the world over read him and read him again is his profound commitment to the truth about who God is and who we are, about what a true knowledge of God and of ourselves requires of us. Yes, it is true that when we read Packer, we are sure that he sees the same world we do, that he lives in the same world we do.

In his latest book (one that actually grew out of lectures he gave at the Laity Lodge), “Weakness is the Way,” he writes,

When the world tells us, as it does, that everyone has a right to a life that is easy, comfortable, and relatively pain-free, a life that enables us to discover, display, and deploy all the strengths that are latent within us, the world twists the truth right out of shape. That was not the quality of life to which Christ’s call led him, nor was it Paul’s calling, nor is it what we are called to in the twenty-first century. For all Christians, the likelihood is rather that as our discipleship continues, God will make us increasingly weakness-conscious and pain-aware, so that we may learn with Paul that when we are conscious of being weak, then—and only then—may we become truly strong in the Lord. And should we want it any other way?

Good man that he is with deep insight that he has, it is a hard book to read because almost everything in me protests, “I don’t want to be weak!”

And yet, I am.

Because I am, the simple words of Dumas, “Athos uttered a cry of terrified tenderness,” are mine too. And the painful reality is that they are true, in different ways because we are different people, for all of us, wounded people living in a wounded world as we all are. We know what that cry sounds like—it is ours too.

Kyrie Eleison.

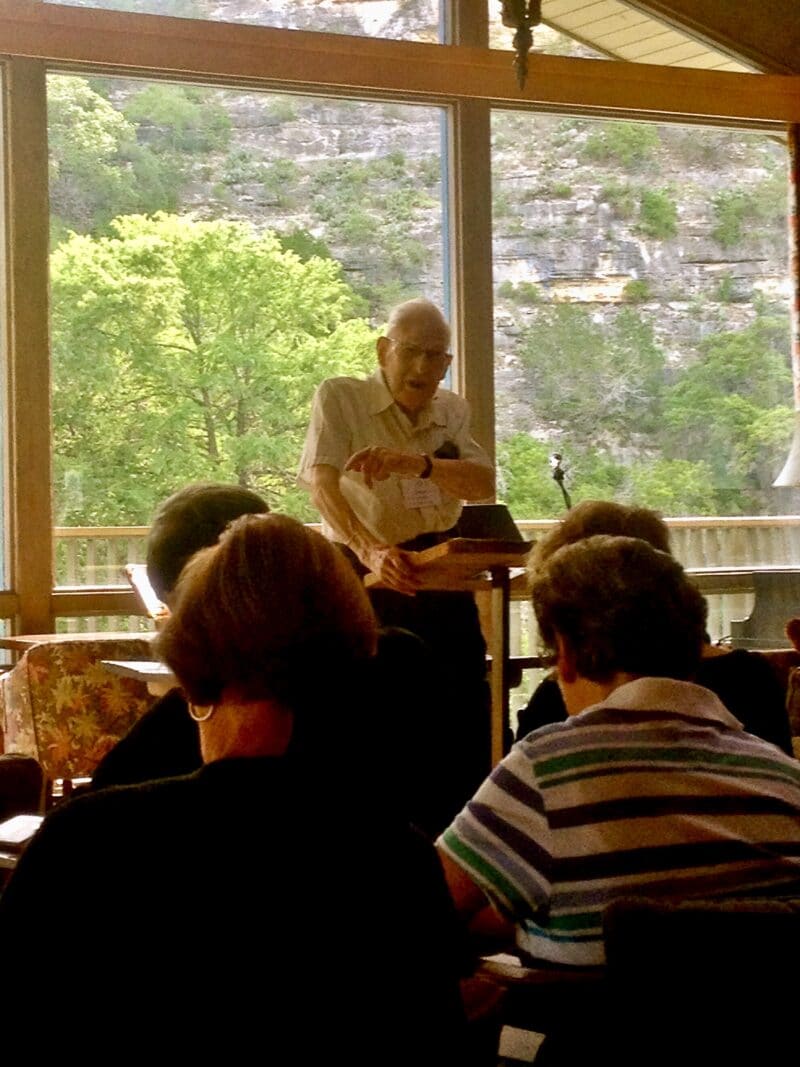

Photos from the Laity Lodge in the summer of 2014. Over its 60 years of history, Dr. Packer was the longest-serving speaker, coming back year after year and for half-century the steadfast friend to Howard E. Butt, its founder. At the heart of their life together the two men longed for liturgy and labor and life to be seamless—and yes, knowing for that to be true they had to become “increasingly weakness-conscious and pain-aware,” that there was no other way for what they believed and how they lived to be coherent.

Over the shoulder, and through the heart.

The image is born of my years pondering pedagogy, of what we teach, the way we teach, and why it matters. Though a thousand things could be said about what good teaching is and isn’t—which in reality is a perennial challenge in every century and every culture—the contrast between “I teach history” and “I teach students” begins to get at the problem. The same is true of philosophy, of engineering, of business, of biology, of literature, and yes, of theology, maybe especially of theology. What is the task of teaching? And when does teaching move from information to transformation?

What changes a mind and a heart? A pedagogy that understands that the truest learning is always and everywhere “over the shoulder, and through the heart.” Simply said, it is why Jesus, the rabbi of the rabbis, begins his teaching by saying, “Come and see.” If you want to know, you will have to enter into what you want to learn; in Michael Polanyi’s great insight, you will have to “indwell” what you want to know. If we fail to show that words can become flesh, our best efforts stumble, which is why the vision of “incarnation” is the heart of the truest theology and also the heart of the truest teaching.

In these days of remembering J.I. Packer, now two weeks after his death, ordinary folk in ordinary places the world over have in an almost-cosmic chorus said, “Packer changed me—everything that matters most to me I see differently because of him.” To think about that for a moment is truly amazing. What was it in him? What was it about him? There was something profoundly transforming of his theological vision and the way he communicated it. Yes, he was brilliant, but it was something more, because he was more. A Puritan scholar of the highest order, yes, but it was his ability to draw ordinary people in—over his shoulder, through his heart—that transformed people throughout the English-speaking world and far beyond. A theology for life in the very best way.

Several years ago I was invited to speak alongside him at the aforementioned Laity Lodge in Texas— Sally Lloyd-Jones was there too as the artist in residence —and I still remember the first presentation I made. Dr. Packer was sitting off to my right in the Great Hall, and I had chosen to begin my lecture by thanking him for his good gifts to me over the years. For a half hour I went on, and on, moment by moment remembering these words, that idea, this time, over the course of years, when he allowed me to come and see.

I walked through indelibly-formed words from “Knowing God,” sentences and even paragraphs that I have read and read again— even memorizing over time because I have read them so often —that I have lived by and with. His deep insights into the nature of wisdom, into the heartaches of life in the world, into the ways that we stumble over knowing how we should live, into the sorrows of everyone’s heart, and into the great grace of being truly known, all have been written into my very being.

But I also remembered when as a young man I traveled far to hear him speak at a gathering of true Catholics, true Orthodox, and true Protestants, each one committed to “mere Christianity” from within the richness of their theological traditions. It was an unusual, even extraordinary time. One morning it was announced that the plenary address for the afternoon’s major session on the challenge of the authority of Scripture within the Catholic Church could not be delivered by the planned-for speaker, a distinguished Catholic scholar, because of illness, but that they were glad to announce that “our good friend, J.I. Packer will speak.” And he did, with great knowledge of a world that was not his as a Protestant and Puritan, but one that he knew as from the inside. That he was trusted by the Catholics to speak for them was very impressive to me; I was astounded, and everyone was graced.

A year later I was driving him somewhere, after having been together for the morning in a session with social and cultural leaders from throughout the city—each having come at my invitation for the privilege of spending a Saturday morning with J.I. Packer—I asked him about his participation in the conference a year earlier. Why were you there? Why did being there matter to you? Of all the words I have heard in the years since then, I remember as if it was this morning him telling me that the older he got the more committed he was to entering into places with people where “a true knowledge of God in Christ was the center.” The words struck me, but it was that he gave flesh to the words that transformed me; I saw them incarnate in his life—and I have lived my life differently because of that.

I reminded him of my invitation to him years earlier to speak in a major gathering for students and their professors on the relationship of “knowing to doing” within the academic world—“Philosophers have interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it”—and the profound insight he had into that challenge, eloquently setting forth a rich vision of vocation for those whose labors were within the academy. That he was such a gifted translator, knowing what he knew and able to communicate it far and wide, has deeply affected my own sense of calling.

And I smiled in telling him that I remembered having him in our home a long time ago, having invited some folks who would proverbially “die” for the gift of spending a lingering lunch with J.I Packer. To my surprise he knew each person’s name within a few minutes, speaking personally to everyone, making sure that each one knew he or she was known. In his own life he lived the conviction that “knowing” was not the same as “knowing about,” and I have not forgotten.

The stories went on because I wanted him to know that his gift to me of “over the shoulder, and through the heart” learning was woven into the very reason I was there that day, entering into days alongside him, speaking about things that mattered to all of us. I was not him and was never going to be. But me being me was somehow blessed because he had gracefully been my teacher, allowing me to “come and see” what it meant to know God, and to know the world made by God. That is the truest teaching for everyone everywhere.

As I said to him that day, “thank you seems small”—but it was from my heart, and today it still is.

Sola Deo Gloria