“You are mistaken; the beautiful is as useful as the useful… more so, perhaps.” These words have been running through my heart the last week.

Making sense of life for life, of what matters and what doesn’t, of what we believe to be the good, the true and the beautiful, and what is not, is as hard as anything I know— and is so for butchers, for bakers, for candlestick-makers, and for farmers, for nurses, for bankers for physicians, for artists too, in fact for all of us, ordinary people living in the ordinary places of the world. Not surprisingly, the question about making sense of life is necessarily about the meaning of life, and therefore about vocation, which is a big word, a complex word, a word that must make sense of the whole of life.

In the rhythms of my heart, this is why I read “Les Miserables” again, and again, lingering through its pages during Lent, wanting to be probed, longing to know more of God and grace, of myself and the world, of what I am and what I should be. It is a story about misery and the miserables, after all; and while never less than that, it is profoundly more than that. If we are drawn into the depths of despair, we are also invited into the greatest of graces. Though I am loath to have favorites of anything, this novel is as good as any that I have read; every time I open it I am amazed at the insight into the human condition. Whether we like or not, good books tell the truth about us as human beings—and Hugo knows us in ways that we probably wish he didn’t, glorious ruins that we are.

If we have seen “Les Mis” as we call it, then we know a bit about Bishop Bienvenu, but only a little bit. The first 125 pages of the book are about him, “the just man” as the author identifies him at the beginning; page by page we learn about him over the course of his life. Who he was. Why he was. And, therefore, the practices of his life. The life and times of early 19-century France which formed him, the social economy of his household, the political economy of his city and nation, the vocation he lived among the haves-and-the-have-nots, the believers and the not-so-at-all in his diocese, the range of relationships and responsibilities that made his life his— from the most personal to the most public, and back again. The whole of life.

And “the beautiful” and “the useful”? They are from a conversation between Bishop Bienvenu and his housekeeper, Madame Magloire, who wonders why he chooses to plant some of his garden in flowers, rather than growing vegetables everywhere, on every square inch. “It would be better to have lettuces than bouquets,” she argues.

Would it be? How would we decide? What does matter anyway? And what doesn’t matter? How do we rightly order the relationship of “the useful” to “the beautiful”? Can we disorder them, misreading their meaning?

If Lent is about anything, it is about the pondering of our loves, the reexamination of our affections. We are invited to ask again about the way we make sense of life, about the ordering of desires, about loving the right things in the right way, about learning to see and hear more truthfully, about caring about what is worth caring about. The task of seeing and hearing is at the heart of the truest vocation because it is born of our hearts, called to pay attention to what is real and true and right as we are— but getting what is real, what is true, and what is right, woven into the fabric of our lives is the challenge for all of us, and why these days and weeks are a season for more serious questions.

The conversation in the bishop’s garden is one that we all know. The ins-and-outs of everyone’s life are about issues like this, choosing between “goods,” the useful, and the beautiful. These are the little things of life that make a life. In our bones we know that all of life is not glorious and grand, and that it cannot all be beautiful. But then what does beauty mean? How important is it? To press the point, “What is beauty? Why is it? What do we believe about it? And what is its relationship to that which is ‘useful,’ the things of life that matter to us, that have utility to us and for us, but are not ‘beautiful’ as we understand beauty?”

These are not small questions, and they mattered for the bishop and his housekeeper. They still matter. While we may believe that the beautiful is important for those who can afford to care about beauty, for the arts and the artists, in reality they are for Everyman and Everywoman, for everyone everywhere. The brilliant Simone Weil, known for her life among the groaners and sufferers of France in the early 20th-century—knowing more of longing and sorrow than most of us will ever know—surprisingly argued, “Workers need poetry more than bread. They need that their life should be a poem. They need some light from eternity.”

The ancient wisdom is that if we are to know the world as it honestly is, we must know ourselves as we honestly are—which requires an honesty about ourselves, acknowledging our frailty. We see through a glass darkly, at our best. As sons of Adam and daughters of Eve we are always frail, disposed to disordered loves, to misreading the meaning of our loves and therefore our lives. But longing to be more fully human is hidden away in every heart; and that, simply, is why the Bishop’s life draws me in year after year. Hugo offers me a man whose humanness is profoundly born of his holiness, one that knows who he is and why he is, a self-knowledge marked by surprising grace.

Poetry more than bread? Lettuces more than bouquets? The questions are not cheap. How do we decide? How do we know? The way we answer comes from our hearts, from the loves of our hearts, from the way we order the loves of our hearts— and the days of Lent are ones for looking again at our loves, because they are ones for looking again at our hearts.

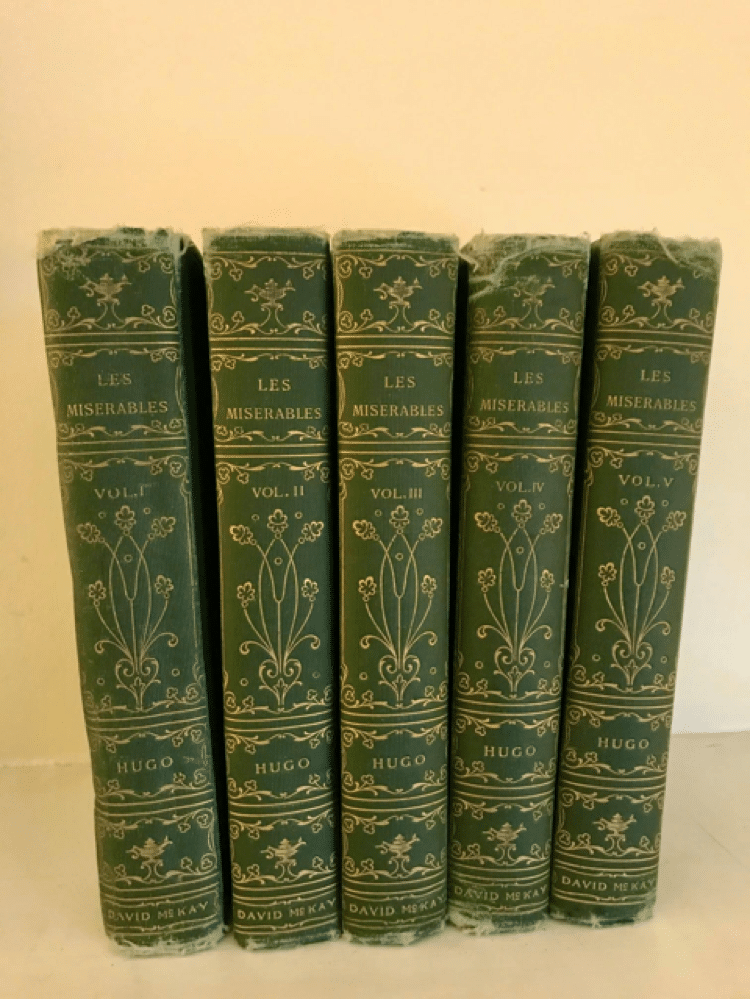

(The much-loved story of “Les Miserables” that graces our mantlepiece, all five volumes, one of the best novels ever written because it is one the truest novels ever written.)