“I don’t like either the word [hiking] or the thing. People ought to saunter in the mountains — not hike! Do you know the origin of that word ‘saunter?’ It’s a beautiful word. Away back in the Middle Ages people used to go on pilgrimages to the Holy Land, and when people in the villages through which they passed asked where they were going, they would reply, “A la sainte terre,’ ‘To the Holy Land.’ And so they became known as sainte-terre-ers or saunterers. Now these mountains are our Holy Land, and we ought to saunter through them reverently, not ‘hike’ through them.”

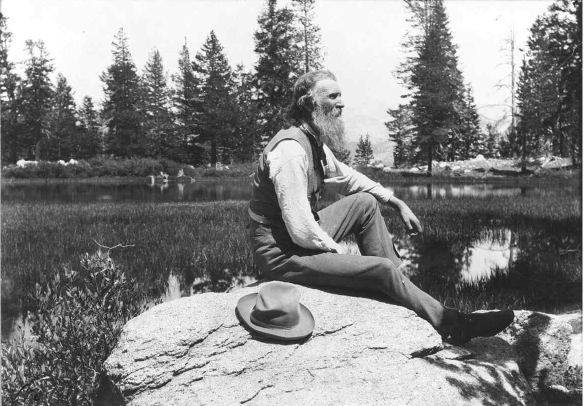

— John Muir, Scottish-American naturalist

Not so long ago I was speaking to a group of folk who work in the marketplaces of the world. Gathered together in San Francisco, my assignment was to think with them about the idea of coherence, especially about the necessary relationship of generosity to justice. With a rare seriousness they have taken up a year of learning together, asking questions about vocation and the common good, pressing into the complexities of cities and societies with unusual rigor, longing to understand their responsibilities amidst issues that often seem overwhelming. The longer I listened, the more impressed I was.

In our hours together we talked about a thousand things, eager as they were, honest as they were, knowing that their vocations implicated them in the hardest questions about the way we live together, about what a good life is and what a good city means, about who has and who has not, about the nature of a responsibility born of love for their places and their people. There was nothing cheap about the conversation.

But given that we were in the City by the Bay, with the Golden Gate Bridge in its morning glory, the fog and the sun playing upon each other with such seascaped drama, I chose to draw in John Muir and his remarkable redwoods not so far away, wanting them to know more than they perhaps had ever imagined knowing about this patron saint of California. Cross the bridge, then hill-and-dale for a few miles up the coast, and finally the giant trees emerge, towering over everyone and everything, named in honor of Muir, the 19th-century naturalist whose love of the creation still inspires us, especially Californians who remember his life by naming so much of their world in his honor.

Having grown up in the Golden State, with boyish innocence I loved that Muir loved the Sierra Nevadas, especially Yosemite, because I did. My father loved the wonders of the mountains, and taught me why, taking me on countless backpacking trips to Mineral King and more, wanting me to see what he saw, to learn to love what he loved (first of all as a human being, and then too, always, as a plant scientist for the University of California). That John Muir was enamored by this same geography, inviting the whole world to come-and-see what he had seen, has more than interested me for the whole of my life. Now known as “the father of our national parks,” over the years Muir has become a good guide, saunterer that he was, me looking over his shoulder and through his heart, and learning that to see sacramentally is the very center of the truest vision, and therefore of the truest vocation.

But to “see sacramentally”? Even to write of Muir’s “love of the creation” says more than I was ever taught, living and breathing the secularized story of Muir that has been handed down for a century. Plainly, I did not know what I did not know, having no idea what he thought about deeper questions, the ones we all ask and answer. What is the world? What is our place in it? How do we make sense of making sense? How does anyone do that? And yes, finally, how did Muir do that?

Given when I grew up, and where I grew up, the story of Muir was one with no room for transcendence, at least the cosmos of the Hebrew and Christian tradition, a universe called “good’ and “good” and “good” again in Genesis 1. As I got older, reading more about everything, there was perhaps a nod to the American transcendentalists like Thoreau, but they teetered more over into our own homegrown pantheism, unable to distinguish the Creator from the creation, their observations and interpretations eloquent, but sadly falling short of what I yearned to understand.

How to make sense of Muir? How could someone love the Yosemite Valley, speaking of it almost worshipfully, but having no one to worship beyond the grandeur of its rock faces and waterfalls? And then all of this within the prescribed presuppositions about the world that were written into the modern academy, a materialistic determinism that made no room for anything more than what we can see and hear, taste and touch?

At the beginning of the 21st-century, we have a story that has been told, “settled” so to speak, with Muir as our great environmentalist leading our care for the flora and fauna of the Sierras, but as someone who was religiously rootless, a man of the Enlightenment who rightfully rejected the rigors of the Scottish Presbyterianism of his youth, having been set free by Rousseau and others to live free in the world, finding his true humanity in an autonomy from all rules and rule-givers. The definitive biographers of Muir tell that tale again and again, in the worst possible ways choosing eisegesis rather than exegesis as the honored methodology to understand him, reading into his time and life what they believe rather than what he believed. Page after painstaking page there is no attempt to read Muir as the boy he was, becoming the man he became; instead there is a determination to situate him within a world and worldview that was not his.

Being a father and now a grandfather, I cannot imagine the catechetical context of a home like Muir’s, whose uncanny love for the created world was formed by his family, including the memorization of the whole of the New Testament and a third of the Old Testament by the time he was 11 years old, who for the rest of his life delighted in the wild of the wilderness understood through those biblically-grounded lenses. When we read him, and not his interpreters, he writes with compelling beauty of the California he was learning to love, the “golden state” as it is known, seeing out into the San Joaquin Valley, the uniquely fertile inland plain that is 300 miles long and fifty miles wide, with the Sierra Nevadas looming in the distance,

“Therefore, when one stands on a wide level area, the gold immediately about him seems all in all; but on gradually looking wider the gold dims, and purple predominates. Out of sight is another stratum of purple, the ground forests of mosses, with purple stems, and purple cups. The color- beauty of these mosses, at least in the mass, was not made for human eyes, nor for the wild horses that inhabit these plains, nor the antelopes, but perhaps the little creatures enjoy their own beauty, and perhaps the insects that dwell in these forests and climb their shining columns enjoy it, but we know that however faint, and however shaded, no part of it is lost, for all color is received into the eyes of God.”

— John Muir

This is not an isolated declaration or sentence. Muir saw “nature” as God’s world and understood his own work as “discovering the inventions of God,” explicitly giving his life to that end.

There is more that could be said, but not here (please see the resources at the end and begin by reading DeWitt’s essay). I want to come back to Muir’s vision of “sauntering,” of his seeing the Sierras as “holy land,” and yes, back to the gathering in San Francisco. While the literal Yosemite Valley was the centerpiece of Muir’s joy in the work of his life, inviting President Theodore Roosevelt and then all who would come to see what he had seen, it is the image of “holy land” that intrigues me, to see “holiness” everywhere in everything—in the language of 1 Peter, to “be holy in every part of life,” as it is the calling to see where heaven and earth touch in and through the days of our lives.

Which is why the great French philosopher, Simone Weil, came to see that “paying attention” is the vocation set before each one of us. Drawing on the parable we call “the Good Samaritan,” she argued that the expert in the law of Luke 10 had never learned to “pay attention” to what was really there, fixing himself on the letter of the law but missing the meaning of the law. And so, Jesus told a story of a road to Jericho, of two teachers of the law who also missed the meaning of the law, and then of a Samaritan who had eyes to see a human being in need, a true neighbor in need. With unusual insight Weil sets forth the human vocation as one of “paying attention” to the ways that heaven and earth touch, our sight becoming sacramental as we see what is really there in the world in which we live and move and have our being.

My hope for those in the room looking out over the Bay was that they would learn to see their cities as “holy land,” as places with people who were in fact “neighbors” with hopes and heartaches incarnate in the cities of their lives, and then of course their lives as “saunterers” whose callings implicate them, for love’s sake, in the world that is, and in the world that could be and should be— which is what vocation is, always and everywhere.

Do we have eyes that see? For a thousand good reasons John Muir is our teacher, still inviting us to come and see “the holy land” of Yosemite and the Sierras, and more, much more.

For more (the first three are worth indwelling, rich and true in the most important ways; the last two are the “definitive” biographies from above, with academic honor but eisegesis at its worst):

- John Muir, The Writings of John Muir (Volumes I-IV), (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1913).

- Peter and Donna Thomas, ed, Anywhere That is Wild: John Muir’s First Walk to Yosemite (Yosemite National Park: Yosemite Conservancy, 2006).

- Calvin DeWitt, “The Psalmic Soundtrack of John Muir’s Life,” Spring 2015, Plough Quarterly, Walden, NY.

- Stephen Fox, John Muir and His Legacy: The American Conservation Movement (Boston: Little, Brown, 1961).

- Donald Worster, A Passion for Nature: The Life of John Muir (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).