Every Christian loves the Psalms. Even those who do not particularly like poetry, or have the patience to grapple with it, still find moments in the Psalms that resonate within their soul. Who can deny the emboldening tenure of Psalm 23? “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil.” Who is not uplifted by the meditation of Psalm 73? “Whom have I in heaven but you? And there is nothing on earth that I desire besides you. My flesh and my heart may fail, but God is the strength of my heart and my portion forever.” Or who can resist the alluring invitation of Psalm 103? “Bless the Lord, O my soul, and forget not all his benefits, who forgives all your iniquity, who heals all your diseases, who redeems your life from the pit, who crowns you with steadfast love and mercy…” It is this kind of rhetoric that has swarmed our imaginations and made the Psalms fixtures in our prayer lives.

Yet the Psalms are not merely a collection of pithy one-liners for the spiritually desperate. As early as the Church Fathers, interpreters have sensed that the entire Book of Psalms has some sort of grand message, a metanarrative (if you will) that draws all the individual psalms into a cumulative pattern. That is, the Church has perennially wondered about the structure of the Psalter (the name given to the collection of 150 psalms), and how the parts fill out the whole.[i] This is motivated in no small part by the simple observation that the Psalter is divided into five “Books.” Just glance in your Bible at Psalms 1, 42, 73, 90 and 107, and there you will see the headings, “Book I,” “Book II,” “Book III,” “Book IV” and “Book V.” Such organization begs interpreters to ask, What rationale groups particular psalms into one “Book” or another? And what is the relationship between those “Books?”[ii]

A recent approach has been to focus on “the seam psalms,” the psalms that begin and end each Book.[iii] Just as the seams on the shirt you’re wearing are holding together various panels of clothing and giving your shirt its distinct shape, so too these “seam psalms” are like the stitching holding together the five Books, bringing the Psalter into a discernable form. To be sure, each psalm stands alone for its meaning and theology. And yet we are invited to think one level up, about the interplay between the individual psalms; then another level up to think about how the Books interplay.

When we consider those “seam psalms,” we see the Books of the Psalter line up into both a familiar and yet breathtakingly fresh design, a narrative from beginning to end. It goes like this. History has a goal: a new creation brought about through suffering, especially the suffering of the Great Son of David. Again, each psalm has its own meaning and theology, and sometimes that may have nothing to do with history, suffering or the House of David. But the composite message is just that, seen through the “seam psalms.”

Book I: From Death to Ruling the Nations

To start, we’ll consider both Psalms 1 and 2. Together they form the initial, and ultimately enduring, trajectory. These will be the only two I print in their entirety. Read them back to back:

1:1 Blessed is the man

who walks not in the counsel of the wicked,

nor stands in the way of sinners,

nor sits in the seat of scoffers;

2 but his delight is in the law of the Lord,

and on his law he meditates day and night.

3 He is like a tree

planted by streams of water

that yields its fruit in its season,

and its leaf does not wither.

In all that he does, he prospers.

4 The wicked are not so,

but are like chaff that the wind drives away.

5 Therefore the wicked will not stand in the judgment,

nor sinners in the congregation of the righteous;

6 for the Lord knows the way of the righteous,

but the way of the wicked will perish.

2:1 Why do the nations rage and the peoples plot in vain?

2 The kings of the earth set themselves,

and the rulers take counsel together,

against the Lord and against his Anointed, saying,

3 “Let us burst their bonds apart

and cast away their cords from us.”

4 He who sits in the heavens laughs;

the Lord holds them in derision.

5 Then he will speak to them in his wrath,

and terrify them in his fury, saying,

6 “As for me, I have set my King on Zion, my holy hill.”

7 I will tell of the decree:

The Lord said to me,

“You are my Son;

today I have begotten you.

8 Ask of me, and I will make the nations your heritage,

and the ends of the earth your possession.

9 You shall break them with a rod of iron

and dash them in pieces like a potter’s vessel.”

10 Now therefore, O kings, be wise;

be warned, O rulers of the earth.

11 Serve the Lord with fear,

and rejoice with trembling.

12 Kiss the Son, lest he be angry,

and you perish in the way,

for his wrath is quickly kindled.

Blessed are all who take refuge in him.[iv]

Notice how the Psalter begins, literally in the first words, with a blessed man. Our first question, then, is Who is this man in Psalm 1:1? In one sense we could say this is any man, woman or child. Anyone can meditate on the law of the Lord day and night, be “blessed,” be fruitful and prosper. Amen! With such a reading the entire Psalter takes on that perspective. Every psalm can be read for its individual piety and applicable wisdom. But looking carefully, we see Edenic imagery pervading Psalm 1: trees, fruit, streams of water, the blessed man with a law, in the context of day and night, even a blowing wind. All those terms should call to mind a name – Adam! Adam was the first man, and the Lord blessed him (Gen 1:22), and gave him a law. This is, therefore, a picture of perfect humanity. Humanity as it was supposed to be. Humanity as it would be if only the first man led the way in such law-obedience day and night, shunning the counsel of the wicked. But there is the dark hint of Genesis 2:17 in this psalm as well: “In the day that you eat of it [disobey my law] you shall surely die.” For verses 4–6 threaten the judgment of the wicked, those disobedient to the Creator’s law. This first psalm is like that prologue in Peter Jackson’s The Fellowship of the Ring. Which way will Isildur go? Destroy the ring (which is clearly the right thing to do) or selfishly keep it? So too, in the Garden of Eden Adam is given the law of the Lord and no sooner presented with the “the counsel of the wicked.” He is offered life and death. Which way will humanity go?

Well, the journey of a thousand consequences begins with one sin. We do not have to wait long to see the direction humanity takes. In Psalm 2:1–3 “the nations rage” and counsel together to revolt “against the Lord and against his Anointed.” If Psalm 1 is a picture of what humanity was supposed to be, Psalm 2 is how humanity truly is: conspiring in mutiny against their Creator. But the Lord does not fret. In verses 6–8 he has an answer: he will bring the rebellious nations to heal through a new man—who he calls “my King” and “my Son.”

Calling this king the Lord’s “Son” in verse 7 is a clear reference to 2 Samuel 7, so we need to take a brief detour. In 2 Samuel 7 David is promised that he will have an eternal dynasty. Let us remember that: David’s house will endure forever (2 Sam 7:13, 16). And the special moniker for all his ruling descendants is “Son of God” (2 Sam 7:14a). If, however, David’s sons are disobedient the Lord will “discipline him with the rod of men” (2 Sam 7:14b). Thus, Psalm 2 is about the Lord’s response to the mutinous nations: he will install the House of David to rule over them (v. 6), to bring judgement on them (v. 9), and yet also bring salvation to them if they will repent (vv. 10–12). In this way, all the nations will belong to the Son of David; they are his “heritage,” his “possession” and he will rule them with the expected righteousness that Adam lacked.[v]

In bringing these two opening psalms together the general blueprint is laid out: Humanity as it once was and supposed to be, humanity as it is, and humanity as it will be again when the new man, the king, the Son of David and the “Son of God,” is enthroned over paradise remade.

Perhaps you think this is a bit much? Perhaps you think I’ve squeezed too much out of the simple observation that Psalm 2 follows Psalm 1. Well, stick with me and let’s see.

Notice that the superscript to Psalm 3 ascribes that psalm to David. In fact, every psalm to the end of Book I is ascribed to David (except for 10 and 33 which have no superscript). So we see that after two opening anonymous psalms, Book I continues with exclusively Davidic psalms.[vi] Psalms 1 and 2 present the original goal of creation, the current fallen context of creation, and the Lord’s plans through David to achieve his original goals for creation. Psalms 3 and following then trace out the long drama to that end, piggybacking on David’s story.

Additionally, there are two other perennial characteristics shared among the psalms of Book I: David is constantly on the verge of death and yet inexorably praising God for giving him the nations to rule! What a juxtaposition: he suffers and reigns! It is in Book I where we read the famous “yea through I walk through the valley of the shadow of death” (Ps 23:4). Is that just a metaphor? I think not. David believed he would really die. A cursory reading of his story in 1 & 2 Samuel reveals he was constantly on the run. Goliath wanted to kill him; Saul wanted to kill him; even his own son Absalom wanted to kill him (the superscript to Psalm 3 even emphasizes this). But then he has “a table…in the presence of [his] enemies” (Ps 23:5). This Book also has the suspenseful Psalm 18 where David moans that “the cords of death encompassed me; the torrents of destruction assailed me” (v. 4), and then describes the Lord tearing from heaven to rescue him (vv. 6–19), to finally end with “you made me the head of the nations” (v. 43). Psalm 22 is equally striking. It begins with “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me” (v. 1) and goes on to describe his death: “you lay me in the dust of the death” (v. 15). His enemies even gloat over his corpse and take his clothes (vv. 17–18). But in verse 19 everything changes! Suddenly, he is saved and “all the ends of the earth” turn to worship the Lord (v. 27) because David is saved. It is as though he has been resurrected! Book I also has Psalm 16 which Peter understands as a resurrection text (Acts 2:22–32): “you will not abandon my soul to Sheol, or let your holy one see corruption” (v. 10). Psalm 8 is also in Book I, which Hebrews reads as the resurrection and kingly coronation of the new Adam (Heb 2:5–18).[vii]

But, at the risk of getting too far ahead of ourselves, let’s keep our focus on the “seam psalms.” Book I ends with Psalm 41:9’s “even my close friend in whom I trusted, who ate my bread, has lifted up his heel against me.” He is totally abandoned and betrayed: Goliath, Saul, Absalom and now his friends are all against him. All have turned on David, the anointed man, but God will raise him up (v. 10) and “set [him in the Lord’s] presence forever” (v. 10). Forever. Yes, that word from 2 Samuel 7:13 and 16! The word that describes David’s House and the duration of the rule of the “Son of God” over creation.

In all, Book I teaches that the Lord’s Anointed is given a cosmic recovery mission, though it will not follow a straight line. Rather, the climb to Mt. Zion follows a path of suffering. Indeed, it is a path that, for David, draws perilously close to the edge of the grave. Thus, David’s near-death experiences are somehow typological of his quintessential son—the “Son of God”—who through suffering will finally reboot creation and bring the nations to judgement or salvation. We can summarize Book I, therefore, as follows: The Lord has a new man, a king in the line of David, who will pass through intense suffering and come out the other side as the cosmic potentate over the nations and creation, thereby restoring humanity and nature to their primordial divine purposes.

Book II: The House of David “Forever”

Book II, then, reveals something of the nature of David’s eternal kingdom. It opens with a taunt from those aforementioned enemies: “Where is your God” (42:3, 10)? For David never took rulership over the nations. And David never restored creation. To the contrary, it is in this Book where we read Psalm 51, David’s chastisement and subsequent plea with the Lord not to take his Spirit away from him (51:1–4, 10–11). So a new challenges arises (as with any dynasty): How can David hand off his kingdom to his son and keep the dream alive? The climax of the Book, Psalm 72, resolves these tensions. The evidence that God is for the House of David and present with his people is in the justice and righteousness that marks the rule of the Son of David. If David’s reign replants creation and brings humanity back to an Edenic experience, then the nations are saying, “Well, let’s see it!” Let’s see what a new humanity ruled by God’s anointed looks like?

Psalm 72, therefore, becomes the highwater mark of the entire Psalter. Here we have the first Son of David, Solomon (or perhaps David praying for Solomon), describing what happens when a people are led by a king that is both just and righteous (v. 1). There is much to observe here, but we can summarize the psalm like this: When the Son of David rules with justice and righteousness (v. 1) the poor are cared for (vv. 2, 4, 12–14), the population is prosperous (vv. 3, 16), creation is fertile (vv. 5, 16), and the nations submit to this great king (vv. 8–11, 15, 17) as they are equally enfolded into the worship of the true and living God (vv. 18–19). And, as we saw at the end of Book I, this will be forever (v. 19). In short, the answer to the question, “Where is your God?” (42:3, 10) is profoundly this: When you see the exemplary righteousness of the Great Son of David, and the blessing that creates for his people, even God’s enemies will submit to his purposes in creation and redemption, and come in eager obeisance to the glorious Creator!

It is a perfect ending to David’s story (in fact v. 20 means something like “This is the goal of all of David’s prayers”): “Blessed be [the Lord’s] glorious name forever; may the whole earth be filled with his glory” (v. 19) through the righteousness of David’s son. The Great Son of David is the new man who will restore creation, reconcile the belligerent nations to their Creator, and lead a society of righteous- and justice-loving people. Sadly, however, for all of Solomon’s wisdom he also had his folly. Book III, therefore, will lead the reader through another fall: Israel’s exile.

Book III: “The Rod of Men”

If only Solomon had lived up to this vision, Psalm 72 could be end of the Psalter. (In fact, it could be the end to the entire Bible!) In Psalm 72 all the goals of Psalms 1 and 2 are on display to motivate the nations to come and “kiss the son” (Ps 2:12). But Psalm 73 confesses that “my steps had nearly slipped.” Again, this psalm has a unique meaning and theology in its own right. But its placement at the beginning of Book III makes that confession of nearly slipping a kind of corporate confession for all of Israel, through the actions of Israel’s king.

This becomes clear as Book III ends with Psalm 89, crushingly the most depressing of all psalms. For in it the psalmist spends 37 verses rehearsing and celebrating the eternal promises made to David, only to suddenly wheel in verse 38 with these words: “But now you have cast off and rejected; you are full of wrath against your anointed. You have renounced the covenant with your servant; you have defiled his crown in the dust” (vv. 38–39). What!? The Lordhas “cast off” the House of David!? Verse 42 even says, “You have exalted the right hand of his foes; you have made all his enemies rejoice.” His “throne is cast to the ground” and he is “covered with shame” (vv. 44–45). This is, of course, the exile. This is “the rod of men” as 2 Samuel 7:14 puts it. This is the time when God’s fury befell David’s sons—subsequent kings over the generations—because they disobeyed the law of the Lord, shunned righteousness, perverted justice and led the people of God to do the same. In other words, from Solomon on the sons of David, that line of kings that typologically forecast the new man, have behaved just like the old man, Adam. Like Adam they did not “meditate on the law day and night” (Psalm 1:2), but followed in the “counsel of the wicked” (Psalm 1:1 and 2:2). They are, therefore, again like Adam, cast out of the presence of God. “Where is your God” (Psalm 43:3, 10)? Well, he’s not with the House of David!

This is why the psalmist emits in despair “How long, O Lord?” in Psalm 89:46. And he asks, “Will you hide yourself forever? (v. 46)…Where is your steadfast love of old, which by your faithfulness you swore to David” (v. 49)? That is the question of the hour. If God has promised an eternal throne to David, then the exile of his people and dethroning of his sons makes absolutely no sense. Is the Creator giving up on his cosmic redemptive purposes? Is the world lost to sin forever? Will the nations never be brought to obedience? Will humanity never be saved from their wickedness? At the end of Psalm 89 it seems so! Without the line of David, what other hope is there? None.

In turn, the psalmist prays the only words that comes to mind: “Remember, O Lord” (v. 50). And that is it. There is nothing left to say or to ask. That the Lord will remember his promises to the House of David, despite their corruption, is the only hope for Judah and the only hope for humankind. Just as “God remembered his covenant with Abraham, with Isaac, and with Jacob” (Exod. 2:24) which launched the Exodus—God’s greatest act of redemption—so too the people of God need a new exodus to save them from their exile.

Book IV: The Lord God Still Reigns

And a new exodus they shall have. In fact, Book IV begins with the only psalm ascribed to Moses. What better way to start the Book that reflects on life in exile than to hear the words of Israel’s first deliver? The message is clear. As God once acted to rescue his people and plant them in the land, hope now turns that he will do it again. Thus, Book III ended with this prayer, “Remember, O Lord,” and so in a way the Lord is saying, “No, you remember!” Remember Moses. Remember Pharaoh, and how he enslaved you and tried to kill your infants. Remember that with a mighty outstretched arm how I brought you out of the fiery furnace of oppression and idolatry. Remember the exodus! The opening verses of Psalm 90 are, therefore, the ground of all of Book IV: “Lord, you have been our dwelling place in all generations. Before the mountains were brought forth, or ever you had formed the earth and the world, from everlasting to everlasting you are God” (vv. 1–2). The rest of the psalm reminds us that our lives are short, and they are lived in a fallen world (vv. 3–17). But the Lord is “from everlasting to everlasting.” He is a refuge and fortress (91:2) who protects his people (91:9–13), who does great works (92:5), who reigns robed in majesty (93:1), the judge of the earth (94:2), a great King above all gods (95:3), our Maker (95:6), greatly to be praised and feared above all gods (96:4), the one before whom the earth trembles and the mountains melt like wax (97:5), who makes known his salvation and reveals his righteousness to the nations (98:2), forgiving and avenging (99:8), whose steadfast love endures forever (100:5), who inclines his ear and answers speedily when we call (102:2), enthroned forever (102:12), who will not always chide nor keep is anger forever (103:9) “for he knows our frame; he remembers that we are dust” (103:14), clothed with splendor and majesty (104:1), who remembers his holy promises (105:42), and so “rebuked the Red Sea, and it became dry, and he led them through the deep as through a desert; so he saved them from the hand of the foe and redeemed them from the power of the enemy” (106:9–10) because he remembered his covenant (106:45). That is what they themselves—a people in exile, pilgrims in an unholy land—need to remember about their God. Interesting, isn’t it, how full of praise Book IV is, and not complaining!?

To summarize our Psalter tour so far, we can say the following.

Book I: Humanity has fallen from its felicitous primordial state through disobedience to the word of the Lord. And yet the Lord has raised up the House of David, through suffering, to become the new head of humanity.

Book II: When the great son of David takes his throne, he will lead through righteousness and justice, bringing the nations to serve him and the Lord with gladness.

Book III: Only the sons of David have fallen from grace just like the first man, and so now the people of God are cast into exile.

Book IV: Yet the Lord will surely remember his covenantal promises and lead them on a new exodus, and so they wait with thanksgiving and praise for his eternal goodness.

And that is where we are at the end of Book IV, with the prayer “Save us, O Lord our God, and gather us from among the nations, that we may give thanks to your holy name and glory in your praise (106:47).” The last psalm of Book IV recalls the exodus and turns such memory into future hope that the Lord would “save us” and “gather us” to the end “that we may give thanks.”

Book V: Resurrection & New Creation

Book V, then, takes off like a rocket. The opening words are “Oh give thanks to the Lord” (107:1) for “he has redeemed” us (107:2) and “gathered” us from all the lands of exile (107:3). The opening words of Book V are an immediate response the prayer at the end of Book IV! And not only that, but the Davidic psalms are back! They had been few in Books III and IV. But now they’re back like kudzu in Book V, a burst of life after weeks of darkness and downpour. The effect is to swing eschatological. That is, Book V looks to the future with a confidence that the Lordwill put his plan for cosmic redemption back on track with a renewed commitment to the House of David.[viii]

And yet, there is a particularly new emphasis in Book V that weaves itself into this line. It comes in Psalm 110: the king (vv. 1–2) will also be a priest (v. 4)! This makes sense! If sin is what took Israel (and in the larger analysis, all humanity) into exile, then a priest is necessary to end the exile and restore the people to God. Would that we could say more on this point,[ix] but suffice it for now to add to our summary above:

Book V: When the Lord completes his redemption through the House of David, he will do so with a priest-king, because atonement is needed both for the people and the creation.

This Book ends, therefore, where we suspected: with a new creation. The last five psalms, 146–150, heap up “hallelujahs” over and over (your translation might say “Praise the Lord!,” which is what “hallelujah” means). And it is especially pregnant how much creation language pervades this last quintuplet of triumph (just look especially at Psalm 148). The point is clear: the House of David, risen from the sepulcher of exile, has brought about the new creation through his priestly suffering! And now all creation reverberates with praise! Indeed, the very last verse, 150:6, says “Let everything that has breath praise the Lord! Praise the Lord!” Yes, breath! That is the word used in Genesis to describe all animate life that God has created (Gen 2:7; 7:22), once intended for the glory of God, now fallen in sin, will someday praise the Lord forever. In the end, the Creator will have the creation, and the image bearers, he originally designed—when the House of David atones and rises from the grave. The Psalter that began with the man in Eden, ends with a new humanity in a new Eden.

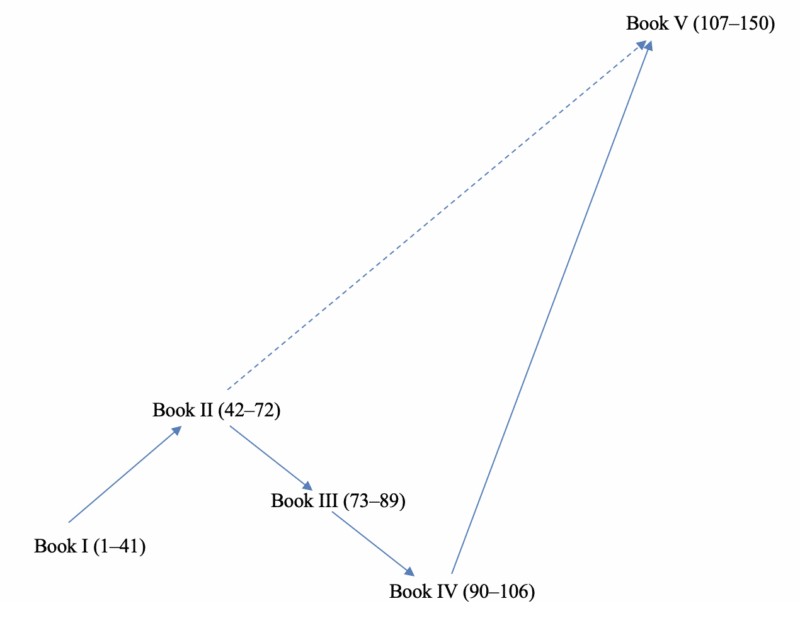

A visual depiction might look like this:

Conclusion

I should repeat: every psalm should be read in its own right, and when they are they do not everywhere fall into harmonious accord with this larger thrust of the Psalter. Yet, this is the scaffolding of the Psalter inside of which the individual psalms live and move and have their being. In turn, while each psalm is its own integrous poem, observing this larger pattern gives each one a slight hue that otherwise goes unseen. Again, in simplest terms, the upshot of observing the structure of the Psalter through attention to the “seam psalms” is the convictions that history has a goal: a new creation brought about through suffering, especially the suffering of the Great Son of David.[x]

In the end Book V caps off the Psalter with a final act that makes its ultimate shape very much like Book I. There, David went through suffering to come out and rule the nations. By the end of Book V we see how all Israel also suffered through the metaphorical grave of exile, only to be led out by the new redeemer, the new priest-king in the line of David, to accomplish God’s purposes of a renewed creation. Thus, the life of David is mapped onto the life of Israel. Book I is the template in David’s life, and Book II is the eschatological hope that that template creates. Then Books III–V is the larger canvass on the history of Israel. Together, David and Israel—both (nearly) dead in the Psalter and now alive in cosmic renewal—adumbrate Christ and his church. For Jesus is the Great Son of David. He is the one who died and rose to subdue the nations. He is the one who models righteousness and teaches justice to his people. He is the one renewing creation, one convert at a time, and ready to draw down a New Heavens and a New Earth forever. He is the priest-king. He is the eschatological new Moses leading his people on a new exodus.

Thus, the new creation has been inaugurated insofar as a multitude of Jesus-followers from across the nations submit to their risen king. But the full and undiluted experience of a return to Edenic life is still ahead of us. We live in between the times, and so the driving questions of the Psalter are still before the eyes of the faithful. Whether we live under Babylonian rule or live in the rapidly secularizing hyper/postmodern age, the Psalter continues to draw our minds to the future with a hope that produces praise in the here and now.

In turn, this opens a beautiful panorama of application for the people of God. The Psalter is first understood as a typological map of the life of the Messiah. And then the life of the Messiah becomes the paradigm of the experience of the church—also a suffering people who reign with their risen king (see my essay on Revelation)! And each individual Christian, then, can see in their own lives the marks of Christ and his people. Thus, the psalms are read through Jesus and the church on their way to individual application. For it is in the church where Christians sojourn, not as spiritual automatons who cut the Christological nerve from individual psalms. Rather, we live in the context of the people of God, the individual discipleship of each of us one significant stone in the larger temple of the church. The temple that is built by the suffering and risen Great Son of David. In the end, those beautiful lines quoted in the first paragraph above, from Psalms 23, 73 and 103 (as just a few examples), are no longer acontextual spiritual placebos, but take on a Christological and ecclesiological ethos, shaping our lives into the image of Christ in the communion of his people.

[i] Steffen Jenkins, “The Antiquity of Psalter Shape Efforts,” TynBul 71 (2020): 161–80.

[ii] We can only wonder who compiled and organized the 150 psalms and when. The best hypothesis in my mind is that it was Ezra after the historic exile.

[iii] Scholars are particularly indebted to Gerald H. Wilson for this approach. His most accessible works are “The Use of Royal Psalms at the ‘Seams’ of the Hebrew Psalter” (JSOT 35 [1986]: 85–94) and “The Shape of the Book of Psalms” (Interpretation 46 [1992]: 129–42). I was first put on to this line of thought by Dieudonné Tamfu, “The Songs of the Messiah: Seeing and Savoring Jesus in the Psalms” (Indianapolis Theological Seminary Symposium on the Psalms, Indianapolis, IN, September 8, 2017).

[iv] All translations in this piece are from the ESV.

[v] For more on the controlling nature of a Davidic theology in the psalms, see O. Palmer Robertson, The Flow of the Psalms: Discovering Their Structure and Theology (Phillipsburg: P&R, 2015), esp. 1–7.

[vi] On the particular question of the authorship of these individual psalms, curious readers can start with the comments by Tremper Longman III in Psalms (TOTC 15–16; Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2014), 25–28.

[vii] Stephen J. Wellum, God the Son Incarnate: The Doctrine of Christ (Foundations of Evangelical Theology; Wheaton: Crossway, 2016), 218–20.

[viii] Here I disagree with Wilson who contends that the point of Books IV and V is to give up hope on all human monarchies (“Shape,” 140–42; “Psalms and Psalter,” 106). Yes, psalms like 146 explicitly state that there is no hope in princes (a lesson politically enthusiastic Americans seem to have to re-learn every four years). But the larger shape of the Psalter is not to turn people’s trust away from all monarchies. Rather, it turns our hope away from monarchies that do not rule with righteousness nor are set up by the Lord on redemptive-historical axes. The eternal house of David, however, is quite different. When it is unrighteous, yes it is just like any nation raging against the Lord (Ps 2:1–3). But when it rules in righteousness (Ps 72:1–7) it is the Lord’s means by which the nations are blessed, and the knowledge of the glory of God covers the earth as the waters cover the sea. In the overall analysis, however, I like Wilson’s concluding statement: “The final form of the Psalter would ultimately affect the way the royal psalms and earlier references to Davidic kingship were interpreted. In light of the distancing that takes place in the later books [the point I think is his under-interpretation of Books IV and V], these references would have been increasingly understood eschatologically as hopeful anticipation of the Davidic descendant who would—as YHWH’s anointed servant—establish God’s direct rule over all humanity in the kingdom of God” (“Psalms and Psalter,” 108–109). “This may even offer a partial solution for the apparent confusion between king and YHWH in such passages as Psalm 45:2–7, where the king appears in Psalm 45:5 to be called ‘God’” (ibid., 109 n. 15).

[ix] The best I can do is point to David S. Schrock’s The Royal Priesthood and the Glory of God (SSBT ; Wheaton: Crossway, 2022), coming out early next year.

[x] For the really keen reader, I would point further to Michael Barber, Singing in the Reign: The Psalms and the Liturgy of God’s Kingdom (Steubenville, OH: Emmaus Road, 2001); C. Hassell Bullock, Encountering the Book of Psalms (Encountering Biblical Studies; Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2001, 2018).