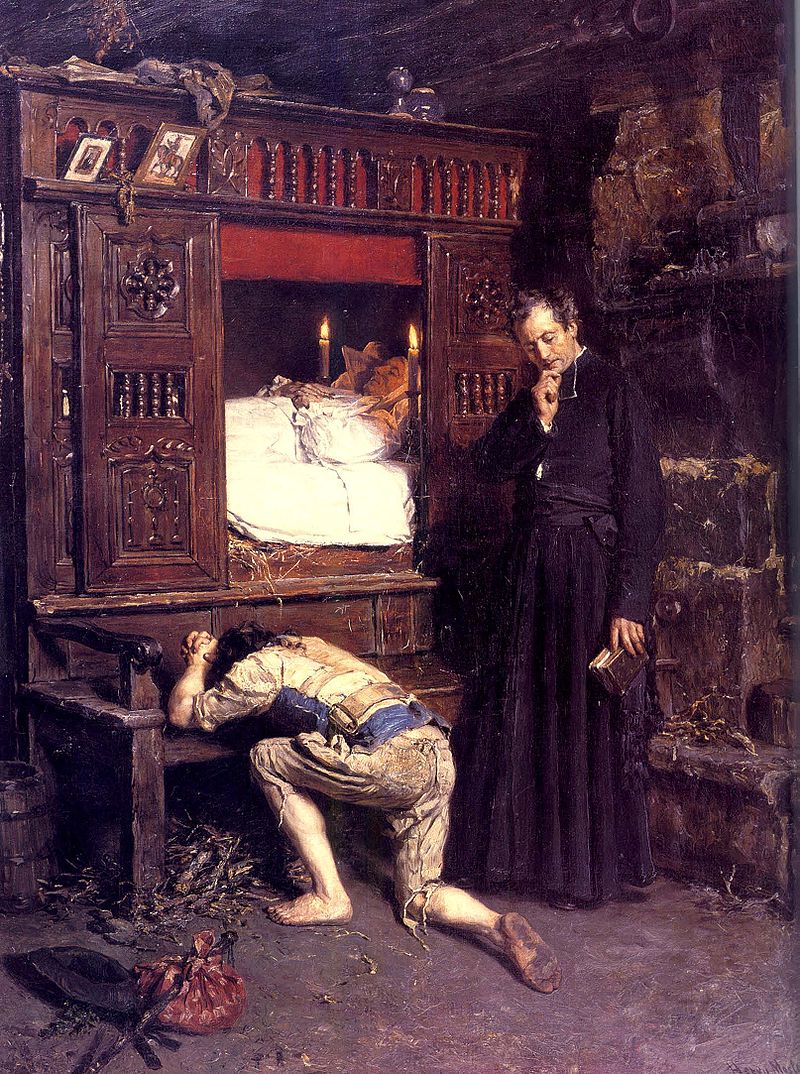

On a recent visit to The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, I was drawn to a painting I had not seen there or anywhere else before. My first guess was that it was by Rembrandt because the overall hue was that rich dark brown the great Dutch painter used so frequently. And like so many great works of art, the painter directed my eyes and guided me through the scene, a favorite device of Rembrandt’s. Two key points, linked by dramatic light, told an intriguing story. The first spotlight illumined the back of a young man, kneeling, with his head collapsed on a bench and his hands clasped before him, as if pleading in desperation. Then my eyes lifted to a spot just above where another man lay on a bed. But it was not an ordinary bed. This one had a low wooden canopy and sliding doors to shut the sleeper off from the outside.

Like other great works of art, this one posed questions that required careful viewing to answer. What was the relationship between these two men? Why was the younger one kneeling? What kind of odd bed was this that could isolate someone so completely? And who was the third character in this plot, off to the right, in less light but not in shadows, dressed in clerical garb, holding a book? I tried to unravel these riddles before reading the title or anything written in the info on the wall next to the picture.

In the bottom left corner of the painting, next to the kneeling man, lay a bag and a stick—the kind a traveler might have over his shoulder as he wandered away from home. The man in the cleric’s robe appeared downcast, looking neither at the kneeling man nor the reclining man on the bed. He gazed toward the ground, perhaps trying to remain as neutral as possible in a scene that grew increasingly disturbing to me the longer I looked at it.

Titles of paintings can tell us a lot. This one was called “Le Retour,” French for “The Return” by Henry Mosler, an American painter from the late 1800s. This work was part of an exhibition of American Painters in France. The curators of this exhibition wrote a bit more about Mosler and this work on the wall under the title and, as I had done, they linked Mosler’s “Return” with Rembrandt’s “The Return of the Prodigal.” They even posted a small reproduction of the more familiar painting with their comments. Dark brown shades dominated both canvases. Both had points of light and contrasting portions in shadows. Both captured that moment when the younger brother returned home after living a life of prodigious waste and “coming to his senses” (see Luke 15:17).

But Rembrandt and Mosler interpreted the story differently and allowed their divergent perspectives to shape their art. In Rembrandt’s, the father welcomed the son home, emphasized through the painting’s illumination on the father’s two hands caressing his son’s shoulders. The scene exudes grace, mercy, and love. Perhaps tears well up in the father’s eyes, with the same emotion he told his older son, “We had to celebrate because this brother of yours was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found” (Luke 15:32).

In Mosler’s rendition, the father is dead! It’s too late for the prodigal! He missed his chance to repent and ask for forgiveness. This painting exudes hopelessness, despair, and perhaps a touch of condemnation. The character off to the right appears to be a priest who has come to pronounce the last rites to a dying man whose life, by the time of this captured moment, has come to an end.

How did Mosler misread Jesus’ story so badly? How could he think the father died? As I stood before his painting, a friend with me said, “Is he saying God is dead? The father in Jesus’ story is God, right?” I agreed. Not only did Mosler miss the point of the story. He lost God and all his grace in the process.

Before we condemn Mosler too severely, it’s worth revisiting Jesus’ story in Scripture and examining how well we understand his reason for telling it, how startling it is, and our need to apply it to our lives today. The Pharisees were muttering about Jesus, saying he “welcomes sinners and eats with them.” (Read the entire chapter of Luke 15 slowly and try to feel the emotional force of each segment.) In response to their judgementalism, Jesus told stories of a lost sheep and a lost coin and how diligently a shepherd and a woman searched for them. These two short preludes set the stage for the much longer and detailed story of a lost son. The Pharisees probably nodded along with the first two stories. “Of course, you’d go after a lost sheep and a lost coin,” they might have said.

Note the very first line of the third story: “There was a man who had two sons.” Right from the start, we must sense that this narrative will up the ante far beyond the scope of the previous two. Most significantly, it’s about two central characters (sons!), not just one (a sheep or a coin – both of which held less value than human beings). The length and emotional details of the story, told by the greatest storyteller of all time, is crafted to shock and convict the Pharisees of their sin of self-righteousness and attitudes of superiority. “Wait a minute,” they would have objected. “The older brother deserved the party – not that disgusting younger brother who deserved nothing!”

I’ve heard Luke 15 preached several times. A few of the sermons stopped when the younger brother came home to the welcoming embrace of his father. “Look at how much the father loves his wayward son,” the preachers said. “Notice that the father was looking for the son, ran after him, hugged him, and threw a party for him. That’s how much God loves you – not as a hired man (the way the son was planning to offer himself) but as a son, given the best robe, a ring on his finger, sandals on his feet, and a celebratory feast, complete with fattened calf and all the trimmings.”

But telling the story of the return of the younger brother without including the part about the older brother is like telling a joke and leaving off the punch line. It totally ignores the first line of Jesus’ story, “There was a man who had two sons.” This is a story of two sons, not one. And if you allow the force of the story to hit you, it’s a story of two sons who were both lost! But only one repented, returned, and received the father’s undeserved forgiveness, grace, and restoration.

The older brother throws himself a different kind of party – a self-righteous pity party. He stayed outside the party his father was giving in honor of the younger brother. Note that the father had to go out to meet the older brother, just as he did the younger (verse 28). The father went after both sons. He ran to meet the younger one on the road. He went outside to “plead with” the older one outside the house. Try to read the older son’s whining soliloquy with all the petty anger you can imagine. “Look! All these years I’ve been slaving for you and never disobeyed your orders. Yet you never gave me even a young goat so I could celebrate with my friends. But when this son of yours who has squandered your property with prostitutes comes home, you kill the fattened calf for him.”

A few details in this rant deserve reflection:

“Never disobeyed”? Can any child make such a claim to any parent?

“You never gave me…? Even more doubtful.

“This son of yours.” Note: He didn’t call him “my brother” and when the father responds, he refers to him as “this brother of yours.”

“…with prostitutes.” How did he know that? Exaggeration for dramatic effect? Anger-induced distortion of reality?

The father’s gentle words to his older son may display even greater grace than what he showered on his younger son. It was gentle. It didn’t rebuke. It highlighted the father’s unyielding presence (“you are always with me”) and unrestricted provision (“everything I have is yours”). It climaxes with the final, powerful last line of the story, “…this brother of yours was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found.”

The curtain comes down on the drama and we never find out how the older brother responded. Did he come inside to the party, hug his brother, and welcome him home? That seems improbable. It’s more likely that he stayed outside, pouting, and clinging to his distorted view of himself (always slaving away, never disobeying), just like the Pharisees who heard Jesus’ story. We don’t know how they responded either (but we can guess).

Now, we must not allow ourselves to respond to this story with self-righteous condemnation of the self-righteous Pharisees. Wouldn’t that be ironic! We dare not think we are immune to self-reliance, self-exaltation, and attitudes of superiority over others. We need to remember the core components of our “desperately sick” hearts (see Jeremiah 17:9 ESV).

Some of us allow our sinful desires to lead us away from God toward sensual pleasures. We think they can thrill and satisfy. We end up in the spiritual equivalent of mud with pigs. Others of us stay home but do so with pride and arrogance. We end up in the spiritual jail of anger and bitterness. Both messes need the cleansing of the gospel. Neither can be cured without divine provision. All need to return to the Father, who alone can forgive, embrace, and celebrate.

The only alternatives to grace-based, cross-provided salvation are self-salvation systems of keeping rules and taking pride in successful obedience. Numerous varieties of these systems exist and not just in other religions. Many so-called Christians create works-based schemes of self-salvation. Take some time to search your heart and see if some Pharisee-ism lurks within. All these religious systems demand perfection. If anyone fails to attain that lofty level of righteousness, they’re out of luck (or atonement or forgiveness or acceptance or love). In other words, as Mosler painted it, there’s no hope. Religious people (like the priest in Mosler’s work) can only look on in grace-less condemnation.

Mosler was a great artist but a poor theologian. His paintings are stunningly beautiful depictions of ordinary daily life. He especially liked to highlight the culture of Bretons in France. (In Le Retour, the son is wearing typical Breton clothing.) Looking at just a handful of Mosler’s works, I wondered why he hasn’t achieved the same level of fame of some of his contemporaries. I hope to search out his other works and see as many on gallery walls as possible. I want to go beyond the only book I could find about his life and work, Henry Mosler Rediscovered: A Nineteenth-Century American-Jewish Artist.[i]

One biographer wrote, “Mosler’s identity can be understood as a mosaic of several broad categories of social attributes: he was German by birth and American by citizenship, Jewish by ethnicity and religion, petit bourgeois by class, artist by profession, a Freemason by voluntary association, and an expatriate who lived in France for almost twenty years.”[ii]

We might get a clue about his worldview through this observation: “A child of working-class background, he learned to fend for himself early in life.”[iii] Apparently, he succeeded. Tragically, self-success often inoculates against grace. If we can overcome poverty or any other difficulty by “fending for ourselves,” we might translate that victory into the spiritual realm, believing we deserve God’s favor. But we do so to our eternal detriment.

In 1879, Mosler’s “Le Retour” (which in some catalogues goes by the fuller title, “The return of the prodigal son) “was awarded an Honorable Mention by the Salon jury and received a unique honor when the French government purchased it for the Luxembourg Gallery, the first time an American would be represented in the official collection of contemporary artists.”[iv] Did such great success fuel an independence from God’s mercy?

Mosler wasn’t the first artist to miss the point of Jesus’ story. He based his painting on an earlier work by Jean-Baptiste Greuze, whose “The Father’s Curse: The Punished Son” seems even more despairing, with a crowd of wailing mourners joining the kneeling son at the bedside of his deceased father.

One writer described Mosler’s scene as “the ragged wayward son, kneeling beside the bier of his deceased mother [sic], whose life he has prematurely shortened, wringing his hands in histrionic anguish.” Without the finished work of the cross, guilt looms as a bottomless pit. Not only did this poor young man come home too late. He actually caused his parent’s death! (It’s hard to tell if the figure lying on the bier in Mosler’s painting is a man or a woman. I assume Mosler painted a man but this art critic didn’t recognize the Biblical basis for the scene).

The first time I went to The Kennedy Center for a National Symphony Orchestra concert, I missed the exit and got lost in downtown Washington. It’s an easy mistake to make. I’ve compared notes with other NSO fans who have shown up late to concerts because of the tricky maneuvering needed to arrive at that fine building. You can see it so clearly from the road but arriving there challenges even the very best GPS. I remember making a mental note for future concerts: “It’s easy to miss the Kennedy Center.” That hasn’t stopped me from going to concerts there. I just pay more careful attention so I don’t miss the exit.

I’m convinced that it’s also easy to miss the gospel. That’s why we’re given so many warnings in Scripture not to be deceived by false teachers (see Jer. 23:16; Matt. 7:15, 24:11; 2 Peter 2:1), not to slip back into works-based righteousness (see Gal. 3:3), and not take pride in our “acts of righteousness” (see Matt. 6:1ff). No wonder we have the entire book of Galatians, fully focused on a group of “foolish” Christians who got “bewitched” by the lure of self-merited salvation. It must be easy to substitute the gospel of grace with some other gospel “which is no gospel at all” (Gal. 1:7).

I’m convinced that it’s also easy to miss the gospel. That’s why we’re given so many warnings in Scripture not to be deceived by false teachers (see Jer. 23:16; Matt. 7:15, 24:11; 2 Peter 2:1), not to slip back into works-based righteousness (see Gal. 3:3), and not take pride in our “acts of righteousness” (see Matt. 6:1ff). No wonder we have the entire book of Galatians, fully focused on a group of “foolish” Christians who got “bewitched” by the lure of self-merited salvation. It must be easy to substitute the gospel of grace with some other gospel “which is no gospel at all” (Gal. 1:7).

For those of us with younger brother tendencies, we need to repent of disdaining or squandering God’s blessings. We need to come to our senses, turn from our pigsties of sin, and bask in our Heavenly Father’s caress that welcomes us home.

For those of us afflicted with older brother syndrome, we need to repent of thinking we deserve God’s blessings. We need to come inside and join the parties God throws for prodigals who have come home.

We all need to cling to Rembrandt’s depiction of the return of the prodigal son and reject Mosler’s. Fortunately for us and for the many lost people God has placed around us, Mosler was wrong. It’s not too late to come home.

[i] Henry Mosler Rediscovered: A Nineteenth-Century American-Jewish Artist; Barbara C. Gilbert, curator; Skirball Museum/Skirball Cultural Center, 1995.

[ii] Ibid, 91.

[iii] Ibid, 92.

[iv] Ibid, 107.