“I’m still angry, and I’m going to be.”

“I’m still angry, and I’m going to be.”

A few years ago I spent several days in Memphis, Tennessee, speaking on vocation as “common grace for the common good.” Believing in the ancient wisdom of “even your own poets have said,” I want to listen to where I am, to speak into where I am, and so thought a lot about the meaning of Memphis in American culture and history.

That meant drawing in the music of Elvis Presley and Johnny Cash, even the classic tune, “Memphis Blues,” but also the novelists Shelby Foote and John Gresham were remembered for their story-formed insights into the Delta region, the South, and what it means to be human.

But also a clip of the film “Mudbound,” which tells the tale of generational grief in the Delta— the geography in which Memphis is the center —the story of those who have and those who do not have, of class-born injustice, and yes, of the terrible wrong of racism in the post-World War II years.

Over the days I gave my heart away, coming to see and hear about a people and a place that was new to me. And while in each address I quoted Martin Luther King Jr, and the importance of his words in and for the city, I did not pretend to know very much about their life, so chose to reflect on my own, growing up in the very middle of “the grapes of wrath” of California’s San Joaquin Valley, with its own history of lament and longing, of class conflict and racial tension. We are perennial people the world over, and mostly we do not have eyes to see the ways that wrongs have to be righted if there is to be an honest sense of life together that makes for a healthy social ecology, for a commonwealth with meaning for all.

One morning I began with a breakfast with one of my longest friends, Tim Russell, at his favorite place, Brother Juniper’s, and then we spent hours driving through the story of the city, especially the story of racial conflict that has afflicted Memphis for most of its history. We drove here and there, getting out of the car to see this, walking to see that, all the while Tim giving me a window into what it means to be from Memphis, a unique city with its own glories and shames.

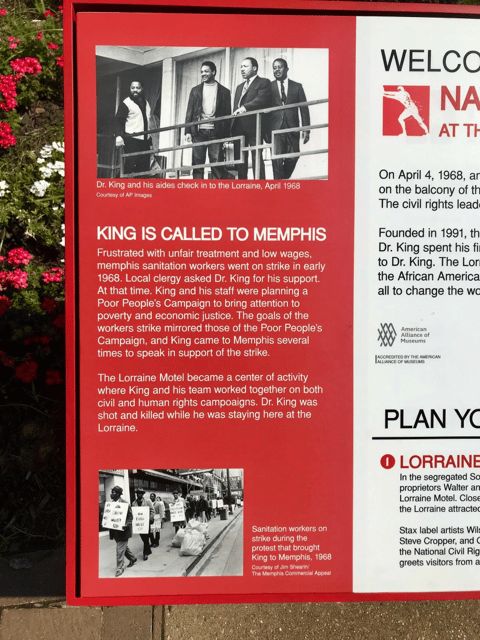

After we lingered at the Lorraine Motel where Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, we walked back to our car and I insisted that we stop at Makeda’s, a little shop on the corner which promised “the best butter cookies in the world!” I asked the woman at the counter about her work, about the business of baking cookies for the city, only blocks from where King was murdered. Before we left with our box of her best, she told me that every cookie was baked with “lots of love!”

I have not forgotten the words, weighty as they were. A central thesis of my time in the city was that vocation is always and everywhere about seeing ourselves implicated, for love’s sake, in the way things are and the way things should be. That she saw her work that way impressed me, specially so in light of where she worked, only a short walk from a place better known for hatred and heartache. As we drove back across town, I asked Tim to tell me more— and he did.

I have not forgotten the words, weighty as they were. A central thesis of my time in the city was that vocation is always and everywhere about seeing ourselves implicated, for love’s sake, in the way things are and the way things should be. That she saw her work that way impressed me, specially so in light of where she worked, only a short walk from a place better known for hatred and heartache. As we drove back across town, I asked Tim to tell me more— and he did.

An unusually good man, a remarkably able man, a very thoughtful man, a specially sensitive man, a deeply passionate man, he said, “I’m still angry, and I’m going to be.” You see, my dear friend Tim was an African-American man. Socially aware, historically conscious, politically astute, theologically trained, if there was anything true of Tim it was that he knew who he was and why he was, and therefore what his life was all about. To say it very simply, he saw into the heart, and into the heart of life.

Perhaps it was that we had driven through the city of Memphis, stopping at the iconic places which tell the tale of tragedy; perhaps it was remembering the long history of racism that has been Memphis, and in too many ways still is. But for whatever reason, Tim spoke plainly and passionately, wanting to make sure that I knew that the wounds of the city had wounded him.

A friend for most of my life, he and I had talked about a thousand things over the years, about love and learning, about work and worship, about the whole of life. And given that my reason for being in Memphis was to keep that long conversation alive, arguing that a recovery of the idea of vocation is integral to the renewal of the city— a thesis which is as true for Jakarta as it is for Bratislava, as true for Singapore as it is for Nairobi, as true for Rio de Janeiro as it is for Sydney, as it is true for Memphis — it is only if we see vocations as common grace for the common good will our cities and societies flourish.

Martin Luther King Jr., so visionary, so eloquent, in his own unique way understood that, believing that street sweepers, like painters and composers and playwrights, are called to work in a way that brings heaven to earth, because work itself has sacramental meaning, connecting the truest truths of the universe with the ordinary lives of ordinary people.

“If a man is called to be a street sweeper, he should sweep streets even as a Michaelangelo painted, or Beethoven composed music or Shakespeare wrote poetry. He should sweep streets so well that all the hosts of heaven and earth will pause to say, ‘Here lived a great street sweeper who did his job well.'”

After speaking on behalf of the sanitation worker’s strike in Memphis on April 3, 1968— poignantly speaking into history with the famous words, “I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land! And so I’m happy, tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord!” —by the power of his presence standing with those who swept the streets of the city, the next day he was killed for these very convictions about God and history, about work and the world, about what matters most and what doesn’t.

A generation later, my friend Tim lived his life for the same vision. A different man in a different time, and too soon, too soon, he lost his life to the plague of COVID-19 in its early days. His wife mourned his death, his friends mourned his death, the city mourned his death, even the angels of heaven mourned his death. For the years of his life Tim was known by all as someone who gave himself away, for love’s sake, understanding the way things are, longing for the way things should be— which is why he was angry at the wrongs of his city and society. But Tim being Tim, his anger was born of love, and in that he taught us all, his great heart holding both sorrow and joy together with remarkable integrity.

A generation later, my friend Tim lived his life for the same vision. A different man in a different time, and too soon, too soon, he lost his life to the plague of COVID-19 in its early days. His wife mourned his death, his friends mourned his death, the city mourned his death, even the angels of heaven mourned his death. For the years of his life Tim was known by all as someone who gave himself away, for love’s sake, understanding the way things are, longing for the way things should be— which is why he was angry at the wrongs of his city and society. But Tim being Tim, his anger was born of love, and in that he taught us all, his great heart holding both sorrow and joy together with remarkable integrity.

And those butter cookies? The ones made with “lots of love”? Of course Tim loved them, and I did too— sure we were that heaven and earth had paused that day, saying for all with ears to hear, “Here was a baker who did her work well.” Good work is like that, a signpost of what someday will be, peering into the Promised Land as we still are.

A signpost of what someday will be? In those few words we have one more window into the meaning of the proximate, of something that is there, but not yet. Not expecting that all will be made well, that all wounds will be healed, that all wrongs will be righted, a signpost is set within the tension of our finite, frail lives, narratively understood as they are; and our beliefs about all of history, the very meaning of life, metanarratively constructed as they are. At our best, this is who we are, all of us, sons of Adam and daughters of Eve, living between the story of our days and the Great Story that makes sense of every day— frail, finite as it so often feels. As the agrarian theologian Norman Wirzba argues, “The way we name and narrate the world determines how we are going to live within it.”

True for the whole of life for everyone everywhere, it was true for Tim. Contracting the coronavirus when he did was because of his love for a woman whom he had long honored, a distinguished art historian and librarian living in New York City, a woman more “mother” of faith and hope and love to him, a woman he wanted to see, for love’s sake, in the last days of her life. In his own body both anger and love were twined together, the meaning of the one written into the other, seamlessly. But without a word like signpost, his anger can only be seen as finally futile— but because it was so profoundly born of love, it was not that, never that.

(These are words I have offered before, notably after Tim died. But given the events of the last days in Memphis, they seem right for these winter days of 2023. For the last two years I have been writing a book, and I can see the light, day after day coming closer to its conclusion. In one chapter, “Love in the Ruins,” I have drawn in ten friends from all over the world— from Belfast in Northern Ireland and Bethlehem in Palestine, from Monterey in Mexico and Bratislava in Slovakia, from Bandung in Indonesia, Kisumu in Kenya and Vancouver, BC too, from Austin, TX, Wichita, KS, New York, NY, Durham, NC and yes, Tim from Memphis, TN —each someone who makes peace with the proximate in and through the vocation of their lives. And I am including a link to the life and work of Vivian Hewitt, Tim’s long friend and mentor whom he was visiting in NYC when he contracted COVID.)

(These are words I have offered before, notably after Tim died. But given the events of the last days in Memphis, they seem right for these winter days of 2023. For the last two years I have been writing a book, and I can see the light, day after day coming closer to its conclusion. In one chapter, “Love in the Ruins,” I have drawn in ten friends from all over the world— from Belfast in Northern Ireland and Bethlehem in Palestine, from Monterey in Mexico and Bratislava in Slovakia, from Bandung in Indonesia, Kisumu in Kenya and Vancouver, BC too, from Austin, TX, Wichita, KS, New York, NY, Durham, NC and yes, Tim from Memphis, TN —each someone who makes peace with the proximate in and through the vocation of their lives. And I am including a link to the life and work of Vivian Hewitt, Tim’s long friend and mentor whom he was visiting in NYC when he contracted COVID.)