“Most of us know what we should expect to find in a dragon’s lair, but, as I said before, Eustace had read only the wrong books. They had a lot to say about exports and imports and governments and drains, but they were weak on dragons.”

When we read “The Chronicles of Narnia” by C.S. Lewis we find ourselves in the stories; they are about us too. Young and old, British or not, they are windows into what it means to be human, into sons of Adam and daughters of Eve the world over. For that reason, I have read them, again and again and again, and the images and words run through my mind, perennially.

So… as I was flying across the West a couple of years ago, looking down on the vastness of Montana and Wyoming on our way from Vancouver, BC, to Washington, DC—after I put down the more weighty, concentration-required book I was reading—I stepped so very easily, one more time, into the fast-paced fiction of Louis L’Amour. A few times a year, mostly when I am traveling in the West, I pick one of his worn-cover paperbacks for a change of pace, knowing that he will capture my imagination from the first page on, telling one more rip-roaring adventure that will have a remarkably brave and good man, a wonderfully beautiful and smart woman, and a horribly mean and malicious man.

While I now know that L’Amour did not know how to finish his stories—it always feels that he just got tired and stopped—almost always he draws me into the world of the West with its 19th-century hopes and heartaches set amidst grand mesas and mountains, often with honorable cowboys and American Indians…and dishonorable cowboys and Indians too.

Deep into the story after only a few pages, Kilrone is set in the borderlands of Nevada, Oregon and Idaho, with an Army fort far from what was then “settled and civilized America,” populated by several first nations tribes, some peaceful and some not-so. A traitorous businessman is the bad guy of the story, making money by selling guns and whiskey to the Indians, all with the hope that when the good guys are gone—i.e. the U.S. calvary all killed at the hands of Medicine Dog and his renegade band empowered by their guns-and-whiskey—he will be able to find more fortune and fame, with political ambition at his heart, sure that history is waiting for him.

This is the way that L’Amour tells his tale:

“At that moment Dave Sproul would step in, meet with the Indians, end the outbreak, and become the man of the hour. From there he might become governor or go to the Senate… and Dave Sproul knew how politics could be used by a man with no scruples, no moral principles, and only a driving greed and ambition.”

Only a paragraph in a longer book, of course, but seeing those words stopped me. L’Amour had his own gift, and it is one that draws me in when I need a break from the rest of my life. When the last page is turned, and the final word is read, I am pretty sure he will not find his way into the literature of the ages—he is not Shakespeare or Dickens, Dostoevsky or Tolstoy, or even Percy or Berry. But reading him again, flying across America, I found myself sure that L’Amour understood us, knowing something simply true about our common life, of who we are and how we live, of what it takes for us to flourish, knowing what a good person is and isn’t, and able to see a bad guy for a bad guy.

Like Eustace from long ago, when we read the wrong books, we miss the dragons in our midst.

And then this from The High Graders – “Nothing in Hollister’s character nor in the breadth of his acres entitled him to the respect he wanted so desperately, and his envy and irritation became a bitter, gnawing thing within him.”

“He had gotten away with it, and with his success had come that sense of power that comes to such men, the feeling that they can go on killing and remain immune. In such men the ego grew and grew, until they rode roughshod over every obstacle.”

I read pretty widely. This past week I finished the most complex novel of John LeCarre that I have ever read, the long lover of his work that I am. Though I fundamentally choose against the cynicism that is his, I understand it, given the terrors of history and the corruption of the human heart. And in the last month I read Amor Towles’ A Gentleman in Moscow, the fascinating story of a man politically “quarantined” for the rest of his life, following the Russian Revolution of 1918, thoroughly enjoying the artful imagination that runs through the novel as it takes us into the heart of the pretense of the USSR. And over the summer I have read more of Tolstoy; almost always I am willing to read more of Tolstoy, opening myself, heart and mind, to his unusual insight into who we are and why we are. Yes, I will read him, and read him again.

But in our travels across the continent, I also stepped back into Louis L’Amour again this month, the story-teller extraordinaire of the American West. Those of you who have read my thoughts on him over the years know that I have my criticisms about this and that, and that sometimes I groan, but it is not those that I want to note here. I honestly think we would do better as a people if we remembered to remember the moral vision that runs through his stories.

With the numbing nature of 24/7 info-glut, making true responses to the world around us seem impossible, with the “whatever” character of choose-your-own-channel news about life and the world, it is too easy to forget that sometimes there is real good and real evil in the world that is beyond the partisan bitterness of this moment in time, so able we are to blame all that is wrong on “them,” and relieve ourselves of our own responsibility. In truth, when all the analysis is done, and when we are overwhelmed by what we know about what we don’t know, it is terribly true that there are people who wake up in the morning intending to hurt others—and it isn’t dependent on their political commitment. Rather it is always about the kind of people they are, about what they love and why they love what they love. Disordered loves are never lovely; instead they wound, always they wound.

And L’Amour understood that too. Not all desires are honorable, and tragically sometimes our desire is to wound others, “running roughshod” over everyone and everything in our way.

There are ways we live that nourish a common good, a commonweal, and there are ways we live that destroy our life together. Knowing the difference and the difference it makes matters if we are to have any future as a people in the world. Historically situated that he was, socially constructed that he was, L’Amour understood that reality in an honest way, and story after story he wrote about the hopes and dreams of ordinary people in ordinary places— and in the end the meaning our choices have for the flourishing of our communities.

Again, always weaving together a surprisingly good man who reluctantly enters into the conflicts of his time and place, an unusually intelligent woman who is called upon to step into history with commitment and courage, and finally someone—often a man but not always—whose self-centeredness ruins what might be and could be and should be for others, in the small universes of L’Amour’s fiction everyone is affected by the bullying selfishness. That poisonous combination of ego and envy eventually brings about a dramatic conclusion with an implosion of the self-absorption before the society as a whole is completely damaged. All is not lost, and we can sleep at night.

Reading the words from L’Amour makes me consider again the world we live in, about the stories that run their way through your consciousness and mine, about the news cycles of every day that weary us and worry us, wondering as we must what it will all mean. His stories are not about the year 2020, and he was not thinking about the persons and personalities that we know, often dominating as they do the landscape of our lives— but he was keenly aware that bullies bully, and that distorted ambitions wound the world.

We are often best known by the questions we ask, and answer. Echoing across the centuries, probing everyone everywhere, are these, simple as they are, profound as they are: do we have eyes to see, and ears to hear?

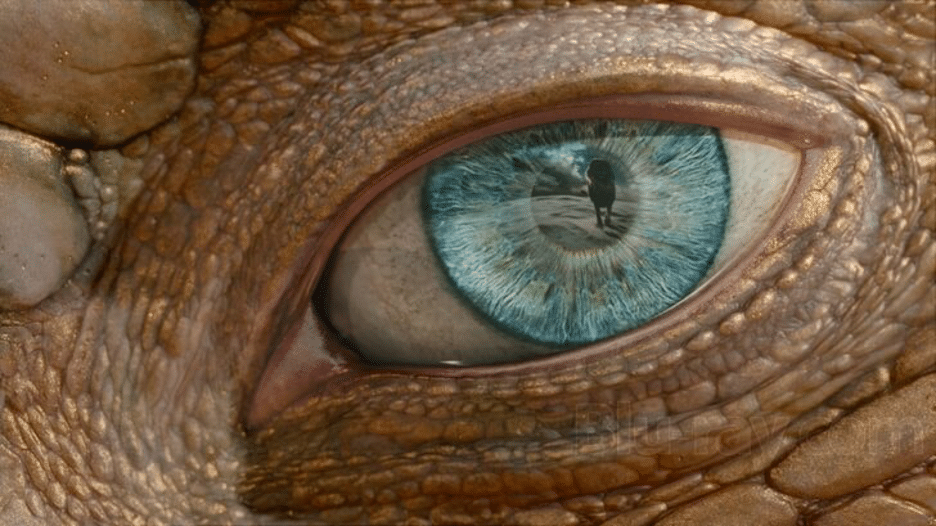

(Photo from the Colorado Rockies, the sagebrush and skies of L’Amour’s literary universe.)