To keep on keeping on.

I first remember seeing those words in a “head shop” in Berkeley in the glory days of the counterculture, and they have run through my heart ever since. Mostly playful at the time, with perhaps a little hippie hope built into the graphic of a cartoonish character making his way through life, I took the words more seriously, wondering even then about the challenge of keeping at it, of staying the course… to keep on keeping on.

Years later this grew into the very heart of my own vocation, and I spent ten years in graduate study thinking about it and then years and years of writing about it, teaching the question to many people in many places. How is it possible to deepen our faith, hope and love — the very meaning of vocation — through the years of life? What is it to become more deeply rooted in who we are and why we are as we move from our early 20s into our 30s and 40s and 50s and 60s and beyond, rather than slowly by slowly discarding what once seemed to matter so much to us?

I thought about this again last night, watching the highlights of the Monday Night Football game of the New Orleans Saints vs. the Indianapolis Colts, when the almost 20-year veteran Drew Brees broke the all-time NFL touchdown record. Through his years in San Diego and New Orleans, he has thrown 541 touchdowns!

His story is surprising.

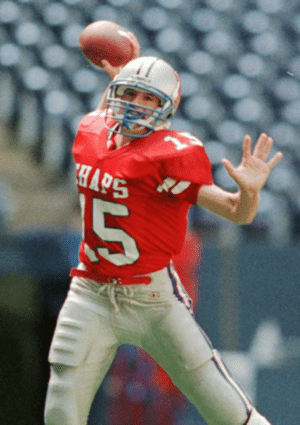

When he was playing his heart out at Westlake High School in Austin, TX in the 1990s, he “starred”— with a perfect record for his senior year and a state championship — but no Texas university even offered him a scholarship. He wasn’t “that” good, and he went off to Purdue, and yes, played very well. As they say, the rest is history, a surprising history.

Earlier this fall I was in Austin for a weekend, speaking at Christ Church Anglican on the meaning of vocation for the church in the world, and as I am wont, I wanted to contextualize as best as I could. So I thought a lot about Texas, and about Austin, before I went, wanting to make sure that the songs and stories which would thread their way through my lectures would be authentically Texan. As the apostle Paul has taught us, “Even your own poets have said…” and they do, and we should listen.

So I began with Willie Nelson, Austin’s native son and my favorite-ever traveling music — “Stardust Memories” — reflecting on the idea of pilgrimage, of the “travelin’” we do in the years of our lives. But then I drew in some of the best-known Texas quarterbacks in recent memory: Vince Young and Colt McCoy from the University of Texas, Johnny Manziel from Texas A&M, and Robert Griffin III from Baylor. And yes, I noted in passing that while each one was judged to be the best of the best college quarterbacks of their day, awarded this-and-that trophy, none made it in the NFL, at least not for long. While that is not a tragedy in and of itself, it is worth remembering, perplexing as it is perhaps. Why? What happened?

And then I offered the hometown hero, Drew Brees, who has surprised everyone but himself, I am sure, with his excellence and brilliance as a player, becoming the “best of the best.” And while often a good football player is not a good man, in Brees’ case they are the same person; from all we can see and hear, he is the real deal, as good in life as he is on the field. That is unusual, and that is worthy of honor.

Then I acknowledged that the question of sustaining our commitments and loves has been the great question of my life. What is the relationship of what we believe with the way that we live? How do we coherently connect our knowing and doing? What does vocation mean? And how do we keep at it, sustaining our vocations in and through the years of life?

That has kept me up at night, and that has kept me at my life. More recently, I have asked, and asked again, “How is it possible to know the world, and still love it?” realizing as I now do that that is the most difficult question of all, the one we are most prone to stumble over. For almost every good reason, we choose not to, knowing enough of ourselves and the world to know that it will cost us too much — that the world is too much and that we cannot bear its wounds, wounded as we are. We choose to suppress and repress instead, knowing but not doing, as we intuitively know that our knowledge means responsibility. And we do not want to be responsible.

Football is not life. Even Texas football is not life. Even Friday night lights are not life. But football is a window into life, maybe a metaphor for life, if we have eyes to see. While most don’t keep on keeping on, some do. Why they do has been the question of my life for the whole of my life.

(And if you want to know more about the way that character and competence meet in the man that Drew Brees is, see this. https://www.si.com/…/drew-brees-practice-alone-reggie-bush-… And here, the story of Brees’ relationship to Ubuntu and its founder, Zane Wilemon, who is the subject of an essay in my new book, The Seamless Life. https://www.ubuntu.life/blo…/news/founder-reflections-people.)