“Beyond the door, there’s peace, I’m sure

And I know there’ll be no more tears in heaven”

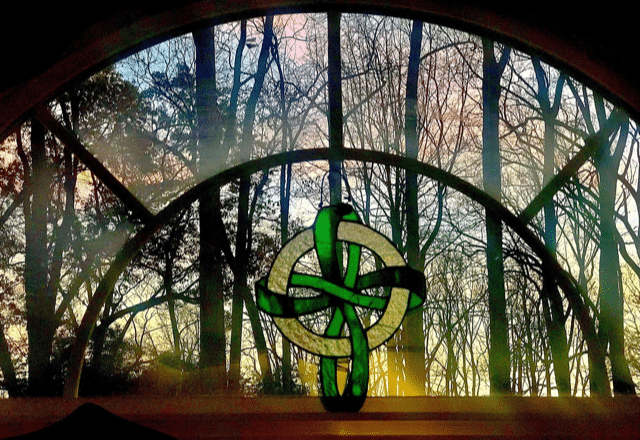

There are mysteries in this life, questions with answers that are hard to come by, difficult to make sense of, perplexing to live with. The meaning of heaven, and the meaning of earth, are like that. What are they? What do they mean? Can we ever know enough to know enough?

This week I have born the weight of death, and of dying. Two phone calls within a few minutes, two dear friends in different parts of the country, one dying unexpectedly in the hours of the night and one who is dying, a long, painful death. I groaned, and am still groaning.

Yes, I know that almost 70,000 people will die of COVID-19 this month in the U.S. alone — and that is only one face of the deaths that plague us day after day in every city and society — and while I care, numbers like that are more than I can bear, more than I can understand, as real as it all is. It is when death comes knocking on the door of one’s own heart that we are face-to-face with what we really believe about life and death.

In my young years I was shocked when death came close. Two neighbor boys died in motorcycle accidents, and in some sense life was never the same on our street. The father of my closest friend died of a hiking accident in the Sierra Nevadas, and that moment is still fresh in the memories of my mind— as it has been since the day it happened. My grandparents and parents have died, as has a brother of mine, and a sister of Meg’s. There are deaths, and more deaths, all over the world, in your life and mine.

“Memento mori,” the ancients have said, “Remember that you too shall die.”

But for me these days are also ones of serious reading, and writing, which involves thinking more carefully and deeply about long-held ideas of telos and praxis, words that most of us don’t use every day, but ones that are written into everyone’s experience all day long. What is the true end of a life? What is its purpose? Why do we get up in the morning? Why are we alive, anyway? Those are questions of telos. But the other word matters too, as it gets at the way we live, the practice of your life and mine. How do we live? What does life look like amidst the ordinary relationships and responsibilities of life? Those are questions of praxis.

My long interest has been the question of coherence, in the necessary, even integral, relationship of telos to praxis, of what we say matters most to us, and the way we actually live. And not surprisingly, given the finite and frail nature of every life, the word “proximate” threads its way through all that I am thinking.

And so I have read Tolkien again, wanting to understand what he understood, to know something of what he knew about these great questions. In his masterful stories there is glory and there is ruin, realities we all know, glorious ruins that we are. There is death too, but in the world of MiddleEarth death is not the final end. The hurts are terrible, the wounds are grievous, and there is no expectation that all will be made well in this life. But there is a promise of something more. In describing his literary universe, he offers the word, “eucatastrophe,” explaining that even in facing the most horrible moments, these “catastrophes” are not final.

The awful heartache of tragic accidents, the evil incarnate in malicious murders, the ravenous disintegration of body and mind through cancers that kill, the slow aging that over the years of life bring the end to life, a painful sorrow each one, and always a grief, sometimes traumatically so. For Tolkien though, in adding the Greek prefix, “eu” — two letters that we also know from “eucharist” — to the word “catastrophe,” he argues that even in the face of terrible terror, there is still more to the story.

Formed by the Christian tradition, and therefore rooted in the promise of the resurrection of all things — a new heaven and a new earth where all sad things finally become untrue — Tolkien looked death in the eye, and still hoped, believing that there would be more to history, and more for everyone who indwells this story through life into death, and beyond.

But I do cry out. I know that there are hours of most every day when I yearn for something other than death. That has been this week of my life, all day long having the deaths of friends burning in my heart. In the thousand of thoughts I have had, having to connect telos and praxis in the face of death’s destruction, the very plaintive words of the poet, Eric Clapton, keep running through the soundtrack of my life. Aching over the tragic death of his young son, he sings a song for me, a song for you, a song for all of us.

“Would you know my name

If I saw you in heaven?

Time can bring you down, time can bend your knees

Time can break your heart,

have you begging please, begging please

Beyond the door, there’s peace, I’m sure

And I know there’ll be no more tears in heaven”

And so I sigh, unable to think about the sorrows of the week without sighing again — even as I believe with all of my heart that there will be no more tears in heaven.

Please, we pray.