Understandably, there are not many songs about Judas Iscariot. But in 1991 the band U2 released a rock ballad called “Until the End of the World.” In an expression of equal parts confusion and bravado, the song attempts to articulate Judas’s inner thoughts on the night he betrayed Jesus. It is initially set at the last supper where Jesus is “talking about the end of the world.” But does Jesus talk about the end of the world at the last supper, in Mark 14? No. He talks about the end of the world in the famous “Apocalyptic Discourse” one chapter earlier, in Mark 13.[i] The song’s setting then moves to the Garden of Gethsemane, still later in Mark 14, where Judas reflects, “In the garden I was playing the tart, I kissed your lips and broke your heart. You, you were acting like it was the end of the world.” But again, this lyric misplaces Jesus’ “end of the world” discourse into another episode in the Gospel. Jesus spoke of the end of the world in Mark 13, not 14.

Is this simply poetic license, the freedom artists take to rearrange source materials for dramatic effect? Or have Bono and the boys alighted upon something deeply profound: that Jesus’ “end of the world” discourse in Mark 13 is actually about his betrayal and passion? I can’t say that I know the authorial intent behind the song, but it does raise a provocative suggestion: that in Mark 13, in his “end of the world” discourse, Jesus is actually talking about himself. The most popular interpretations of Mark 13 are that he is talking about the razing of the temple by the Romans in 70 A.D. and/or he is talking about his second coming. But if we first observe some surprising links between Mark 13 and the rest of the Gospel in Mark 14–16, then we discover a third interpretive option: that Jesus is principally talking about something a lot sooner—his agony in the garden, betrayal by Judas, trial, crucifixion, resurrection, and regathering of his disciples in Galilee. What appears at face value in Mark 13 to be about the destruction of Jerusalem’s temple and/or the end of the world is primarily about the destruction of Jesus’ body and his rising to rule the nations in a new historical aeon.[ii] In this reading, then, the destruction of the temple in 70 AD and Jesus’ return theologically align with the gospel, and the gospel gives an interpretive lens to these other events.

The “Apocalyptic Discourse” in Mark 13 begins with a focus on the Jerusalem temple, yet it is linked to the remainder of his Gospel. As Jesus is coming out of the temple, one of his disciples asks about how wonderful it is (13:1), to which Jesus replies that the entire edifice will be demolished (13:2). This may seem shocking to us, but Jesus had been engaging in symbolic actions and making judgmental comments against the temple for the last two chapters, even already predicting its destruction.[iii] Perhaps this is why the disciple comments on it being so “wonderful,” as though to say, “Are you sure Jesus? Will it really be destroyed?” Jesus’ answer in 13:2 is “Most certainly! Every bit of it.” Naturally, with such a cataclysmic event, the disciples want to know “when will these things be, and what will be the sign when all these things are about to be accomplished” (13:4)? That is the context for Mark 13. The rest of the chapter goes to answer that two-pronged question: when will the temple be destroyed, and what is the sign leading up to it?

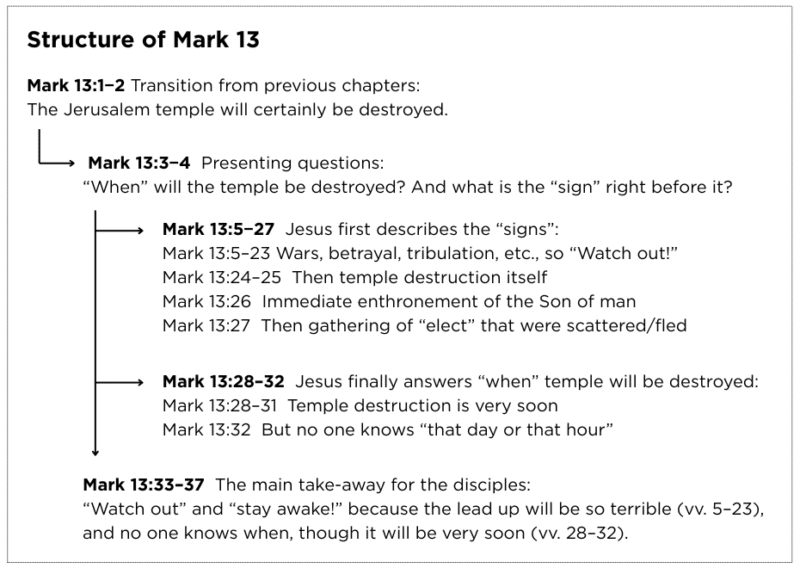

Jesus addresses that second half of the question first. Everything from verses 5 to 27 considers “what is the sign,” and it actually turns out to be many signs. We will come back to them. But for now, it is vital to notice Jesus does not answer the principal question of “when” until verse 32: “concerning that day or that hour, no one knows.” Thus, Mark 13 is a simple answer to the question “When will the temple be destroyed?,” though Jesus delays the answer until almost right at the end. For all the length and complexity of Mark 13, Jesus’ answer is profoundly simple: nobody knows. This lack of knowledge then leads Jesus to one point of application: therefore “watch out, stay awake!” (vv. 33, 35, 37). For while no one knows the day or hour, it will nonetheless come soon (vv. 28‒30). And thus you have the entire point of Mark 13 on the discourse level: the temple will certainly be destroyed, but no one knows when, so stay alert/take heed/watch out/stay awake because it is imminent.[iv]

We can visually depict this flow of thought as follows.

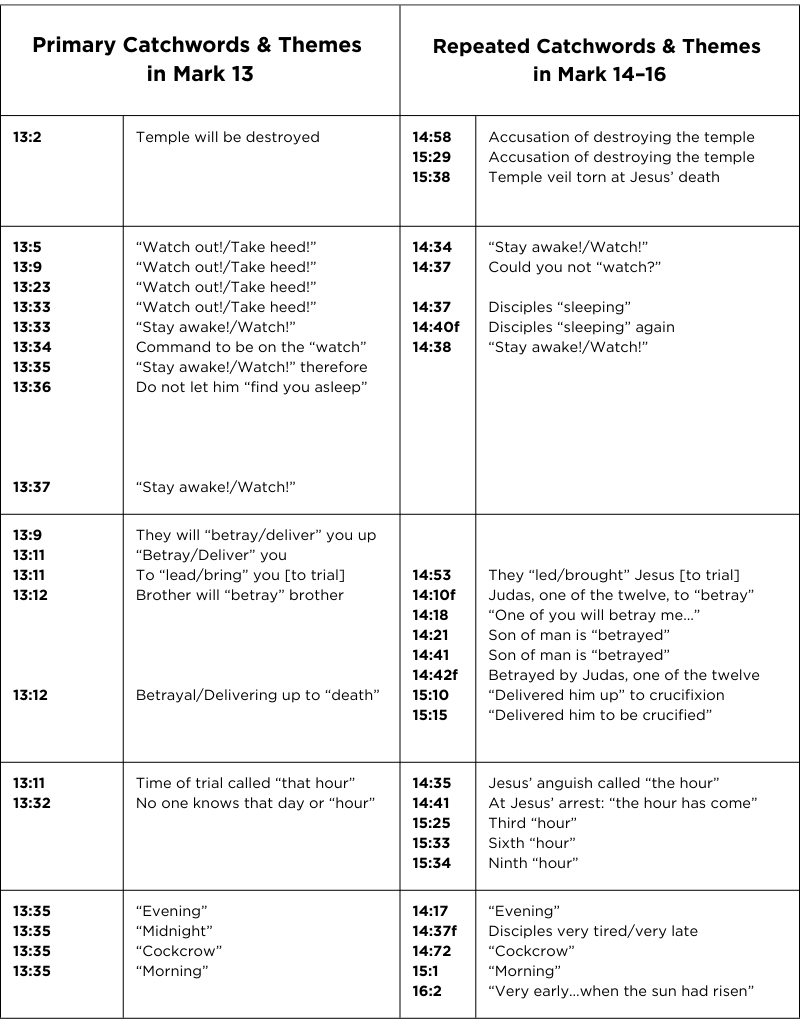

To say that Jesus delays his answer to the immediate question until verse 32 in no way diminishes the importance of verses 5‒31. In fact, the reader can see how Jesus is indeed developing to his concluding remarks by the way the catchword “watch out” is used throughout these verses. It is the first thing Jesus says in verse 5, is then repeated in verses 9 and 23, and again repeated in the concluding paragraph in verse 33. It is then set in parallel with “stay awake” in 13:33, which is equally repeated in verses 34, 35 and 37.[v] This refrain, to “watch out” and “stay awake,” therefore, dominates the entire chapter.[vi] Below we will observe how these terms are also used in Mark 14 to recall the discourse of Mark 13.

We can also observe additional catchwords and themes. The word “deliver up/betray” is repeated three times in 13:9–12.[vii] The word “hour” is also repeated in 13:11 and 13:32. The watches of the night are singled out, “evening, midnight, cockcrow, morning,” in 13:35. And the charge not to not to fall “asleep” in 13:36 concludes the “watch out/stay awake” motif.

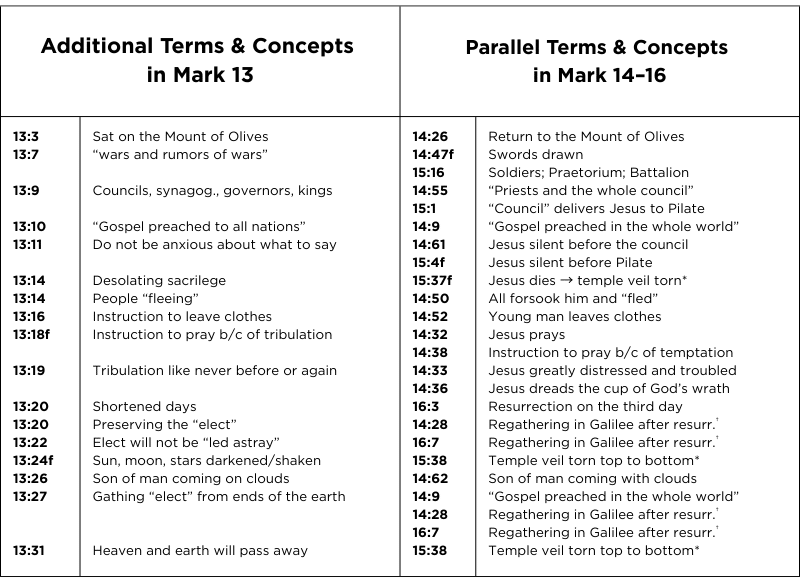

The effect of these repeated catchwords and themes is that they stay with the reader as the next chapters of Mark develop. Here is a list of catchwords and themes organized sequentially through Mark 13 that then reappear in the rest of the Gospel.[viii]

The effect of these connections is really quite profound and far-reaching: Jesus is speaking primarily of his death! In Mark 13 Jesus clearly projects something of the future using particular terms and themes. Then, the same terms and themes are used to narrate Jesus’ agony in the garden, betrayal, arrest, trial, and crucifixion.[ix]

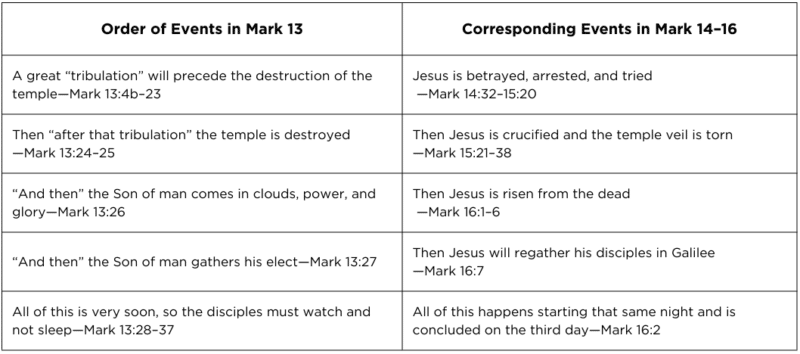

As mentioned, the principal point of Mark 13 is that the temple will be destroyed (v. 2). And his disciples must “watch out” and “stay awake” for many reasons (vv. 5, 9, 23, 33–36), because “concerning that day or that hour, no knows [when]” (v. 32). Then, as Jesus goes to pray in the garden (itself reminiscent of Jesus’ command to pray in 13:18–19) the disciples are again instructed to “stay awake/watch” (14:34, 38), and subsequently upbraided when they do not “stay awake/watch” (14:37) but instead are “sleeping” (14:37, 40, 41). Then, at that very moment Jesus says, “the hour has come”—the hour when “the Son of man is betrayed” in 14:41. With the emphasis on the unknown “hour” from Mark 13 (vv. 11, 32), as well as the repeated focus on betrayal throughout Mark 13 (vv. 9, 11–12), Mark 14:41 reads very naturally as the sudden coming of that hour—the hour of the temple’s destruction, only now applied to Jesus’ hour of betrayal!

Incidentally, all of this takes place in the “evening” (14:17) and late in the night (cf. 14:30, 38). And then Jesus’ trial takes place as the “cock crowed” (14:72) and into the “morning” (15:1). Those are the watches of the night when Jesus said “the hour” might suddenly come in 13:32, 35.[x] This is why Jesus is so disappointed in his disciples in 14:27—they are not watching, they are not ready for “the hour.”

In sum, therefore, when Jesus predicts the destruction of the temple in Mark 13, using all these catchwords and themes, the reemployment of such catchwords and themes reveals he is actually talking about his own destruction. The hour of tribulation is coming upon Jesus, as his brother betrays him into the hands of those who seek to destroy him (cf. 11:18).[xi] That is “the sign” (or collection of signs) for which they must “Watch out!” (vv. 5 and 23). It is all downhill from there to Jesus’ death.

To appreciate this reading, we need to understand why, when asked about the destruction of the temple, Jesus would then talk about himself. Why would Jesus’ death equate with the destruction of the temple?

Mark 13 is not the first place that Jesus theologically aligns himself with the temple. The most recent example is the Parable of the Vineyard in Mark 12:1–11.[xii] Scholars are largely in agreement that this parable is about how the temple leadership’s unfaithfulness (12:2–5) and murder of the son (12:6–8) will result in the destruction of the temple (12:9). The “son” is of course God’s son, Jesus (cf. 1:11) who they seek to arrest and destroy (11:18; 12:12). It is in that context that Jesus quotes Psalm 118 which is about a temple (re)construction: “The stone that the builders rejected has become the cornerstone.” Jesus is the stone that is rejected, that will now become the keystone of the new temple building.[xiii] He says this in the context of predicting his murder. The point is that killing Jesus will result in the destruction of the temple. But more than that, after they kill him, he himself will be the sine qua non of the new temple.[xiv] A resurrection prediction!

It is not hard to understand, therefore, that the destruction of one means the destruction of the other. Jesus can speak of his death, therefore, as the destruction of the true temple of God. The physical temple in Jerusalem, a very powerful religious symbol, creates the opportunity for Jesus to make such a theological case about himself, and what his death ultimately means. “Destroy me and you destroy to the true temple of God. But as I’ve already predicted three times (8:31; 9:31; 10:33–34), I will also rise on the third day—and that will mean a new and permanent temple.” Mark 13, therefore, “affords a framework within which to ponder the crucifixion of Jesus…[its] universal significance, ultimate power, cosmic sweep.”[xv]

On some level even Jesus’ false accusers are tapping into this in 14:58. They say, “We heard him say, ‘I will destroy this temple that is made with hands, and in three days I will build another, not made with hands.’” This false accusation is a muddled-up conflation of his resurrection predictions—three days—and his actions/words against the temple in chapters 11‒12. Jesus never says that he himself would destroy the temple. He simply says it will be destroyed. But it sure is interesting that these false accusers link that idea of the destruction of the temple with its rebuilding three days later. They have collapsed Jesus’ teachings on the destruction of the temple with his prediction of resurrection, albeit in a confused way with one bogus detail: that Jesus would be the one doing the destroying. Thus, on some level it was in the air that Jesus equated himself to the temple and that his resurrection somehow meant a new temple, in the air enough to form a credible false witness.

The same equation is ironically happening at the very moment of crucifixion too. In 15:29–30 Jesus’ mockers decry, “Aha! You who would destroy the temple and rebuild it in three days, save yourself, and come down from the cross!” The irony is that they are the ones destroying the temple at that very moment! And again, the three days are associated with temple-rebuilding. When Jesus is indeed saved in three days that will mean that very temple-rebuilding! Mark would have the readers draw all these conclusions, especially at the moment of the resurrection which casts an interpretively clarifying light on all this.

In sum, in Mark 13 Jesus is asked about the destruction of the temple and then goes on to describe the destruction of his own body. He can do this because the meaning of the temple—the presence of God, the place of atonement and reconciliation—is truly and ultimately applied to himself. So, to ask about the destruction of the temple in Jesus’ mind is to ask about his own crucifixion. But unlike the physical building in Jerusalem, Jesus’ temple-body will rise again, forever to remain therefore the sole locus of atonement, reconciliation and the enjoyment of God’s presence and pleasure.[xvi]

But what about the darkened sun and moon, falling stars, and shaking heavens in 13:24–25, and the coming of the Son of man in the clouds in 13:26? Are these not clear “end of the world” images? Why would Jesus use end of the age language to describe his resurrection? This is where Bono comes back into the story.

Mark 13:24‒25 states, “But in those days, after that tribulation, the sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light, and the stars will be falling from heaven, and the powers in the heavens will be shaken.” Since the presenting question of Mark 13 is about when the temple will be destroyed, this language of a disrupted cosmos reads like an apocalyptic description of just that, the destruction of the temple. This makes sense because the temple was decorated with heavenly lights, especially on the veil. The reason for this was to represent both creation itself, but also to underscore that behind the veil is the very throne room of God. Hence the veil was embroidered with the lights of the heavens (sun, moon, and stars) to represent that separation, just as the skies above separate us from heaven itself, the true throne room of God.[xvii] The tearing of that veil at the very moment of Jesus’ death in Mark 15:37‒38 is understood within this symbolism, and therefore becomes the fulfillment of 13:24‒25. As Greg Beale and Mitch Kim put it, “Since the temple veil was embroidered with the starry heavens, its tearing would be an apt symbol of the beginning of the destruction not only of the temple (which itself symbolized the cosmos) but of the very cosmos itself.”[xviii] Since the temple represents the heavens, and Jesus is the new temple, his death, therefore, can be apocalyptically described as the failing lights, falling stars, and fracturing of the heavens. Moreover, quite explicitly, it says in 15:33 that at the time of Jesus’ crucifixion “darkness was over the whole land” at midday.

Yet, in the same breath—right after his comments on the sun, moon, and stars—Jesus also states, “And then they will see the Son of man coming in clouds with great power and glory” (13:26). That is typically taken as a statement of Jesus’ return—his second coming—at the end of the age. Passages like 1 Thessalonians 4:16‒17 and Revelation 1:7; 14:14‒16 back this up. But we should note that 1 Thessalonians and Revelation were both written after Jesus’ resurrection and ascension, whereas Mark 13 records things Jesus said before his resurrection and ascension. The perspective is therefore different. While it is obvious that 1 Thessalonians and Revelation speak of Jesus’ return, it is not so clear in Mark 13. Why would Jesus’ disciples, the immediate audience in Mark 13, think Jesus meant a second coming when it is evident from the rest of the Gospel how they struggle to comprehend his first coming? He had never spoken of a second coming before. Why should the disciples think that is what he meant?

Rather, it is far more likely that the disciples would have thought of Daniel 7:13‒14.

13 “I saw in the night visions,

and behold, with the clouds of heaven

there came one like the Son of Man,

and he came to the Ancient of Days

and was presented before him.

14 And to him was given dominion

and glory and a kingdom,

that all peoples, nations, and languages

should serve him;

his dominion is an everlasting dominion,

which shall not pass away,

and his kingdom one

that shall not be destroyed.

It is vital to observe here that the movement of Daniel’s “Son of Man” is not from heaven to earth, but from earth to heaven! That is, the “Son of Man” goes up, not down. We can see this in that he comes “to” the Ancient of Days (God), not from him. What is going on in Daniel 7 is a priestly figure who comes into the presence of God and receives authority to both rule and cleanse the earth.[xix]

Back to Mark 13, the “Son of Man coming in clouds” therefore is the resurrection and ascension. That is how Jesus enters into the presence of the Ancient of Days to receive a kingdom and a people that shall never pass away. While this may sound avant-garde, Peter Bolt points out, “There is a long tradition of interpreters stretching from the church fathers down to today that recognizes Daniel 7:13–14 to be a prophecy of Christ’s ascension, or, more precisely, of his exaltation to heaven.”[xx] Thus, in Mark 13:26 Jesus is predicting that after his tribulation and death he will be resurrected and raised to heaven whence to rule the nations!

The disciples are charged to stay awake and watch for all that. Sadly, they do not. But, since the elect cannot be ultimately led astray (13:5, 6, 22), after the resurrection they are all (minus Judas) regathered (16:7)!

The order of events, therefore, in Mark 13 are reflected in the order of events in Mark 14–16 as follows.

This in no way detracts from the doctrine of Christ’s “second coming.” To the contrary, it brings helpful clarity to Act 1:8‒9. There, Jesus tells his disciples that their gospel-witness will go in the power of the Holy Spirit to “the ends of the earth.” Then immediately Jesus is taken up in a cloud. Thus, the means by which Jesus rules the nations qua Daniel 7:13‒14 is through the spread of the Spirit, the gospel, and his people. Then, as the disciples are looking on as Jesus ascends in a cloud, an angel tells them, “This Jesus, who was taken up from you into heaven, will come in the same way as you saw him go into heaven” (Acts 1:11). Thus, Jesus goes both to and from heaven in clouds. Mark 13 is focused on the prior, 1 Thessalonians and Revelation 1 and 14 are focused on the latter and Acts 1 is focused on both. This reading of Mark 13 therefore, in addition to its coherency within the text of Mark, brings Jesus’ ascension and return into theological alignment—both of which result in different kinds of Jesus’ sovereignty over all things.[xxi]

Apocalyptic language is fascinating. It supplies the speaker/writer with the opportunity to describe mundane things in deeply theological categories. To many Jesus was but a helpless martyr. Or a criminal. Or a madman. Little reason to pay attention to his execution. But in Mark 13 Jesus prepares his disciples to see his death in far more cosmological terms. His death is nothing short of the destruction of the very true temple of God. As such it can be described as a ripping apart of the very universe—so grand and consequential that only the language of rocking and shaking all of space-time will suffice. Thus, “the apocalyptic discourse has put us in a position to see the passion of Christ in cosmic terms: the cross at the end of the world.”[xxii]

Yet in the same breath Jesus also prepares his disciples for a new world in which Jesus rules the nations as the resurrected shepherd-king, destined to bring in his elect. All of this is preceded by his agony and betrayal, so his disciples must “watch out” because it will all commence very soon—indeed that very night!

But did not Jesus warn his disciples that they will go through such distress and that they should, therefore, pray? It seems incongruent, then, when those things happen to Jesus after he prays in chapters 14‒15. But no, it is not incongruent at all, but something deeply profound: Jesus goes through all the distress first! Thus, as the attack of the world continues against Jesus’ people (still more distress and tribulation to come; still more reason to watch out and to pray), Jesus’ people can know that he doesn’t call them into anything he doesn’t go through first. Thus, his people have great confidence in him as a merciful and faithful high priest (cf. Heb 2:14‒17). And his people can know that their persecutions are no accident, but mysteriously part-and-parcel of their divine calling, for the life of Messiah becomes the pattern for the life of the Church (cf. Col 1:24‒26). And equally they can know that their efforts in preaching the gospel to all the nations (Mark 13:10) can certainly never be in vain! And insofar as Jesus is with his people always (cf. Matt 28:18‒20), he is with them specifically in their sufferings (cf. Acts 9:4).[xxiii]

Appendix: Additional Terms & Concepts in Mark 13‒16

[i] Sometimes Mark 13 is also called “the Olivett Discourse” because Jesus delivers it while sitting on the Mount of Olives, which is just across the Kidron Valley from Jerusalem. Parallel passages can be found in Matthew 24 and Luke 21. Because of the necessary brevity of this essay, we will focus on only Mark 13.

[ii] Peter G. Bolt calls Mark 13 the “apocalyptic preparation for the passion.” See his The Cross from a Distance: Atonement in Mark’s Gospel (NSBT 18; Nottingham: Apollos, 2004), 85–115; specific quote from p. 91.

[iii] Nicholas G. Piotrowski, “‘Whatever You Ask’ for the Missionary Purposes of the Eschatological Temple: Quotation and Typology in Mark 11‒12,” SBJT 21.1 (2017): 101‒10.

[iv] Similarly, R. T. France, The Gospel of Mark (NIGTC; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002), 504‒506.

[v] Micah D. Keil says these terms are “almost synonymous” (“The Open Horizon of Mark 13,” JBL 136.1 [2017]: 157). So close in meaning are these terms, “watch out” and “stay awake,” that the latter is often translated as simply “watch.”

[vi] Joel Marcus, Mark 8‒16: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (AB 27a; New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2009), 879, 903.

[vii] Depending on the translation, the same word is rendered “betray” or “deliver up/deliver over.”

[viii] All English translations of key words are kept consistent with the Greek behind them so that English readers can here see where the same words are being used and reused.

[ix] R. H. Lightfoot, The Gospel Message of St Mark (Oxford: Clarendon, 1950), 50–54.

[x] See esp. R. W. L. Moberly, “The Coming at Cockcrow: A Reading of Mark 13:32–37,” JTI 14.2 (2020): 213–25.

[xi] Bolt summarizes well: “The hour when the world will destroy the Messiah has now arrived—the destructive sacrilege, beyond all acts of sacrilege; the great distress, beyond all human distress” (Cross from a Distance, 111).

[xii] See as well Timothy C. Gray, The Temple in the Gospel of Mark: A Study in Its Narrative Role (Grand Rapids: Baker Academics, 2008), 100–102, 158‒62.

[xiii] Or Jesus could mean the capstone (Marcus, Mark 8‒16, 808‒809). Either way, it is the determinative stone.

[xiv] See esp. G. K. Beale and Mitchell Kim, God Dwells Among Us: Expanding Eden to the Ends of the Earth (Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 2014), 86‒89.

[xv] R. H. Smith, “Darkness at Noon: Mark’s Passion Narrative,” CTM 44.5 (1975): 333.

[xvi] We can even go a step further and say that derivatively the same is true of the church. Jesus is the cornerstone/keystone around which the rest of the new temple is constructed: his “elect.” See John Paul Heil, “The Narrative Strategy and Pragmatics of the Temple Theme in Mark,” CBQ 59.1 (1997): 76‒100.

[xvii] Beale and Kim, God Dwells, 54‒55, 60‒63, 174.

[xviii] Beale and Kim, God Dwells, 93.

[xix] Nicholas Perrin, The Kingdom of God: A Biblical Theology (Biblical Theology for Life; Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2019), 68‒69.

[xx] Bolt, Cross from a Distance, 94. He then cites Hippolytus, Cyprian, Cyril of Alexandria, Hugh of St Victor, John Calvin, A. T. Robinson, and R. T. France, among others. See particularly France, Mark, 500–501, 530–40.

[xxi] It also solves the early Christian problem of with what scholars have called “the non-event of the Parousia.” Because Jesus didn’t come back in the lifespan of the first believers, as the thesis goes, the next generation of Christians had to scramble to create a “delay of the Parousia” theology. As such, that would mean texts like Mark 13 and 1 Thessalonians and Revelation show discrepancy and dispute with the pale of “orthodoxy.” Not so if Mark 13 is not about the Parousia in the first place.

[xxii] Bolt, Cross from a Distance, 112.

[xxiii] Special thanks to Brandon Buller and Brian Carter for their research and editing help on this.