Over the shoulder, through the heart. An image that I never get far from, I think and think about it some more. My PhD studies drew me to learning about learning, especially the way that belief becomes behavior, that behavior becomes belief; and in the years of my life I have wondered time and again about the conditions that make us “us.”

As complex as complex can be, the answer as rich as most university curricula, along the way I have also spent many years thinking about the pedagogy of Jesus, the rabbi of rabbis. From the beginning, his invitation was to “come and see.” To understand him, to see and hear the meaning of what he was saying, one would have to come and see the way he lived, to come and see what he cared about, to come and see what mattered to him and what didn’t.

Simply said, to learn over his shoulder, through his heart.

This past month I was in British Columbia (Burrard Bay pictured), about an hour-and-half hour east of Vancouver along the Frazer River, nestled in a Benedictine monastery, taking part in the annual global retreat of the Institute for Marketplace Transformation, the vision and work of Paul Stevens, a very good man and a very good professor. That I spent several years teaching “marketplace theology” at Regent College came about principally through him, as the very idea was his. Believing in “down to earth spirituality” and in “the seven days of faith” (titles of two of his many books), he has spent most of 50 years teaching that at Regent, and at 87 still does. Though he has “retired” three times, no one who watches carefully could imagine that he has—because he spends the hours of his life still fully engaged in the work of his work, still pursuing the vision that he has followed for the years his life, longing to make more sense of what work means and why it matters to God and the world.

A native Canadian, he has lived across its many miles, from the Maritime provinces in the far east to Vancouver in the far west, where he has lived for most of 60 years. Deeply rooted as he is, he loves the world, and the world loves him back, especially Asia (though I have talked with people in Africa and Europe as well, who like others in Indonesia and Singapore wanted me “to be sure” that I gave warm greetings to Paul, whom they knew to be my colleague and friend).

For our weekend, Friday to Sunday, people flew in from Hong Kong, Manila, Taipei, and Seoul, so that they could be with Paul again, learning from him as they have, loving him as they do. And this was not a “goodbye” gathering in any sense—though someday that too will happen—but only one more year of the great gift of being his student, which means being his friend. People with serious commitments to the work of their own lives chose to fly halfway around the world to be there, believing with him in the hope of “the transformation of the marketplace.” For more justice to be done, for more mercy to be shown, for more humility to be practiced.

A million miles from the compartmentalization of many, a compartmentalization always distorting work’s meaning—the worst of both capitalism and communism does that—Paul’s long work has been for the gospel of the kingdom of God to leaven the labor of life, in the words of two more of his good books, to show that “work matters” because “the other six days” matter. And because to be his student means that one is drawn into his loves, his deep belief in the goodness of good work is infectious—even in the very wounded world that is ours—and people cannot not do anything but take his hope home.

I would be remiss in not drawing in his long-loved love, Gail, who was his companion in every adventure for more than 60 years. During our years in Vancouver, she was like a big sister to Meg, drawing Meg into relationships and responsibilities that had been Gail’s, notably the University of British Columbia Faculty Women’s Club, which became the surprising center of most of Meg’s great loves there, the Bible study, the hiking and snowshoeing groups especially. A year after we left, Gail passed, leaving all who knew her with both mourning, and joy. Like Paul’s, her very face was as a human being fully alive.

When we left Vancouver, entering back into the deeper, longer vocation of our lives, Paul asked if I would be willing to join him in his work of the Institute, and without a blush I told him that I would “crawl back to Vancouver to do something with you,” and that has meant writing sometimes, speaking sometimes, and many conversations, all gladly given.

A year ago he asked if I would speak for the annual retreat for IMT. “Of course,” and I did. He wanted it be about the book, The Seamless Life, so that the Institute could make a course from the lectures, offering them to students around the world. For quite a while I gave my heart to thinking it all through again, and then offered eight lectures, all born of the themes of the book, “a tapestry of love and learning, worship and work.”

And now we will see. What is clear even a week later, is that everyone who was there—from Asia, from Africa, from San Diego and Seattle, from Washington DC, from Toronto and Calgary—were there because, like me, they have made the choice to learn from Paul Stevens, over his shoulder, through his heart, which for everyone everywhere is the way the deepest, truest learning always happens. We learn nothing that matters very much any other way.

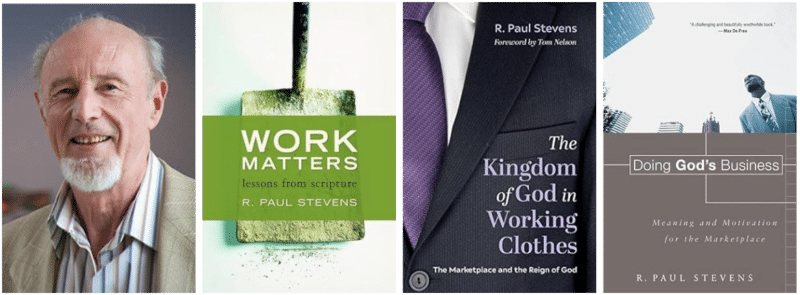

Paul Stevens and three of his many books.