The first verb recorded in Scripture, the first action word in the great God narrative, is create: “In the beginning, God created . . .” He created the heavens and the earth; the stars and the planets; the sun and the moon; birds, beasts and fish; light and dark. And of course, God created man and woman—in his own image.

As God’s image bearers, is it any wonder that the same verb motivates so much of the human experience? You might say creativity, in its many forms, is our superpower. It certainly sets us apart from the rest of creation. We create art and architecture, airplanes, printing presses, vaccines, and my personal favorite, chocolate chip ice cream. Inventions and discoveries across the centuries bear witness to the creative spirit hard-wired within us.

Our inherent desire to create is surpassed only by the intrinsic value ascribed to every individual created in the likeness of the God of the universe. That’s not to say that we are valued because we are creative, quite the opposite. Our self-worth and dignity are not predicated on any measure of creative proficiency, which is happy news for me considering my talent on the piano ends with Chopsticks and my artistic eye has an astigmatism.

We humans have a nasty habit of comparison that often tricks us into believing we are not only not creative, but also not worthy. Of course, the truth remains that we are the crown of God’s creation. As Bill Fullilove writes in a previous TWI article, “The Christian contention is that dignity comes because we are created in the image of God…we have an inherent dignity, one that can be marred and defaced, but never truly lost.”

So, when we’ve misplaced our self-worth or the harmful actions of others have all but destroyed our dignity, that first verb—our superpower—can help restore a right understanding of value according to God’s design. Again, creativity comes in many flavors, but for the sake of illustration, let’s consider art. More specifically, let’s explore how the pondering and practice of painting can help us rediscover and hang on to our own humanity. Hanna Rose Thomas will be our first guide.

Bringing Light to the Dark Spaces: Hannah is a young British artist and human rights activist who has organized art programs in hotspots around the globe, gently teaching and ministering to survivors of horrendous violence and loss. Her soft-spoken nature belies a bold and compassionate spirit and her mission to give voice to the voiceless through the healing properties of art.

While studying Arabic in Jordan in 2014, Hanna began working with Syrian refugees. In the decade since then, she has conducted art workshops in Jordan, Iraqi Kurdistan, Bangladesh, Nigeria and Romania, teaching women how to paint their self-portraits and share their stories one brushstroke at a time. The workshops are designed to help women process traumatic memories, begin to heal, and ultimately reclaim their voice and dignity.

“Art is a way to express that which we cannot find words to express,” says Hannah. In particular, she believes the painting process creates a way to attend to others, to actually listen and be present in another person’s grief or trauma. Only then can true healing begin.

Here are a few of the women she has met along the way:

Ladi lost her innocence the night Boko Haram militants invaded her home in Northern Nigeria. Kidnapped, threatened, and molested until she consented to be married to one of her assailants, Ladi soon gave birth to a son. She named him Emmanuel—God with us.

Ladi lost her innocence the night Boko Haram militants invaded her home in Northern Nigeria. Kidnapped, threatened, and molested until she consented to be married to one of her assailants, Ladi soon gave birth to a son. She named him Emmanuel—God with us.

Ladi managed to escape her captors with Emmanuel and find relative safety in a camp for internally displaced people (IDPs). She and her son are among Nigeria’s nearly 2.4 million IDPs, forced from their homes due to brutal violence and religious persecution. Those who find shelter in the camps are the lucky ones. In the past two decades, terrorists have ravaged villages in Northern Nigeria, murdering more than 50,000 Christians.

Though many camp residents have welcomed Ladi, many more have shunned her and the child born of unspeakable cruelty.

Fahima’s story is also grim. A Yezidi mother from Northern Iraq, Fahima’s life forever changed in August 2014 when ISIS terrorists overran her town of Sinjar. ISIS murdered thousands of Yezidis that summer, sold women and children into sexual slavery, and turned young boys into child soldiers. Fahima’s own four-year-old son was ripped from her arms during the turmoil, a little boy lost forever.

Fahima gave birth to her second child while imprisoned in Syria. During that time, the young mother surprisingly was never sold into slavery or forcibly taken by ISIS fighters. She believes this good fortune was because her captors did not consider her as beautiful as the other girls who shared her misery. A captive no longer, Fahima’s tears continue to fall, not for herself, but for the son who will not know her face.

Samkina is a Muslim Rohingya refugee from Myanmar, a victim of ethnic cleansing and a witness to genocide. In 2017, the teen was forced to flee her home as members of the Burmese military surrounded her village and set it ablaze. Even as residents scattered, the military opened fire on the villagers, killing many including Samkina’s father. Though Samkina managed to escape with her mother and siblings, the traumatized teen remains haunted with grief over the father left behind. “We had to leave my father’s body behind,” she recounts.[i] No burial. No closure. No dignity.

Since the early 1990s, more than one million Rohingya like Samkina have left their home to escape unspeakable violence and human rights abuses. Many now live in congested refugee camps in neighboring Bangladesh. Former Administrator of USAID Mark Green says there is nothing like the experience of going to an IDP camp in Burma. He describes one visit where he met a young father desperate for answers:

He told me that all of his children were born in that camp. He could not leave without written permission, which he had never gotten. He said there were health facilities but no doctors, classrooms but no teachers, and the only food he had was what the U.S. had provided. He looked at me and said, ‘My question is, what do I tell my son?’ That just shattered me,” says Green. “Food assistance is crucial. Medical assistance is crucial. But we also have to find ways to have settings for people in which they can be human, where they have space to express their humanity.[ii]

Hannah’s solution has been to create space with art. There in Bangladesh, she spent mornings painting with the children who called Kutupalong refugee camp home. Later in the day, she would sit with the women of the camp, listening to their stories and learning their faces. “The children all wanted to paint colorful flowers, trees, and memories of their homes in Myanmar,” says Hannah. “Looking around the camp I could understand why—there was scarcely a tree in sight!” Once a thickly forested habitat of the endangered Bangladeshi Asian elephant, the area had been stripped of vegetation to make space for tens of thousands of bamboo refugee shelters.

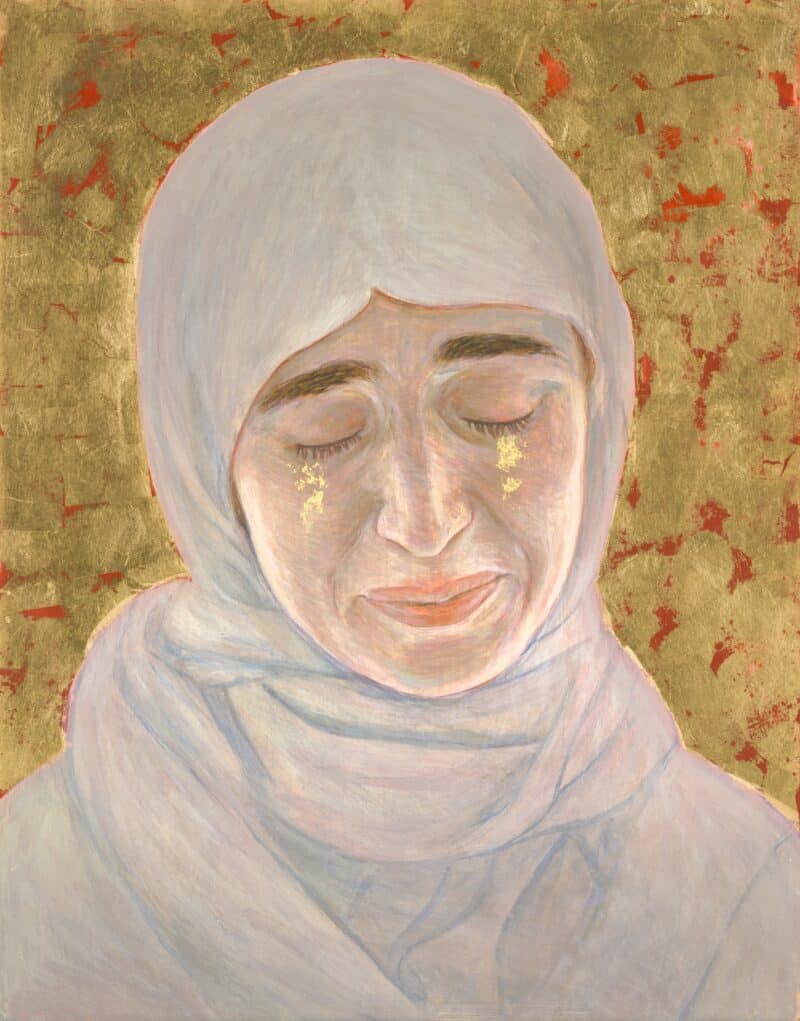

In Iraq, many of the Yezidi women Hannah worked with chose to paint themselves with tears of gold streaming from their eyes, tears that symbolized their grief for loved ones lost. “It’s like the words of the psalmist,” marvels Hannah, referring to Psalm 56:8, which says, “You keep track of all my sorrows. You have collected all my tears in your bottle. You have recorded each one in your book.”

The idea that no tear had been forgotten and her students valued every tear shed inspired Hannah to pick up her own paint brush and capture the resilience and dignity of the women survivors. Applying her training in early Renaissance painting and iconography, Hannah has painted a series of portraits collected in her newly released book, Tears of Gold. Ladi, Fahima and Samkina are among the subjects featured in this volume, which also includes portraits of survivors from other conflict areas, including Afghanistan, Ukraine, China’s Xinjiang region, and Palestine.

“I love the prayerful approach of iconography and the idea of seeing paintings themselves as a form of prayer,” says Hannah. “This technique is embedded in my approach to the paintings of the Yezidi women in particular because when I returned home, I was devastated by their stories. I couldn’t really return to modern life as I knew it. I needed to stop and engage prayerfully with each woman’s story.”

Hannah’s portraits—painted with egg tempera, precious pigments and oils, then gilded in gold leaf—are reminiscent of Byzantine icons or sacred paintings, such as Titian’s Mater Dolorosa or Our Lady of the Don by Theophanes the Greek. The technique requires building up thin layers of paint in a movement from darkness to light. In icon painting, this process is symbolic of the journey the soul makes as it moves from darkness to light. Hannah’s choice of methods is contemplative and painstakingly slow on purpose.

“Time is such a precious commodity in our modern world,” says Hannah. “These time-consuming methods, the process itself, are a form of prayer and lament, a way of attending to and honoring the stories I have heard. At the heart of my work is a desire to show that we are all made in the image of God and of equal value in his eyes, to convey the idea of sacred value in each and every individual.”

In the spring of 2018, Hannah introduced her Yezidi portraits in the UK Houses of Parliament. His Majesty King Charles III (at the time Prince Charles) chose three of the portraits for his 2018 exhibition “Prince & Patron” at Buckingham Palace. “Testimony is an important element of the recovery process from the experience of torture and sexual violence,” notes Hannah. She believes that knowing their voices were going out to the world—that they were not forgotten—gave these survivors great hope. “The advocacy aspect was key to their sense of feeling valued and heard.”

More than amplifying their voices externally, encounters with Hannah’s workshops have helped many of the women recalibrate their own internal voices. For Ladi, the Nigerian mother who escaped her tormentors only to endure scorn from members of her own community upon returning with a son born of rape, an inner awareness has brought newfound joy. “Before, I could not hold a pen or do anything. Now, through this art project, I have learned how to draw,” she shares. “I drew myself and when I looked at it this morning, I saw how beautiful I am!”

Obviously, a few art workshops with a handful of victims will not end the evil realities of conflict, hatred, and persecution. Such a conclusion would be overly simplistic in a world drenched in sin. But disregarding the value of art as a healing agent would also be a missed opportunity. “How different the world would be if we treated each person we met as a reflection of the divine,” says Hannah.

If art holds the power to heal, it also carries the power of influence. Here, we meet another painter, David Labkovski, whose body of work tells the story of life in Eastern Europe before, during, and after the Holocaust.

Remembering, Restoring and Enlightening: The restorative power of art, both practiced and observed, has been captured in a recent documentary from producer Daryl Pugh called, “Healing through Art.” The award-winning program explores the life and work of David Labkovski, whose self-portraiture is a visual diary of the physical and emotional consequences and the human degradation he endured while imprisoned in the Siberian Gulags of the early 1940s. David’s artwork was also his therapy. More important, it is his legacy; a collection that documents the horrors of the Holocaust but also reflects the hope of the human spirit.

“Resilience is not about overcoming or forgetting,” says Leora Raikin, David’s great grand-niece and the Executive Director of the David Labkovski Project. “Resilience is about becoming; becoming our fullest, deepest selves as a result of adversity. We can’t escape the past. It becomes a part of us.”

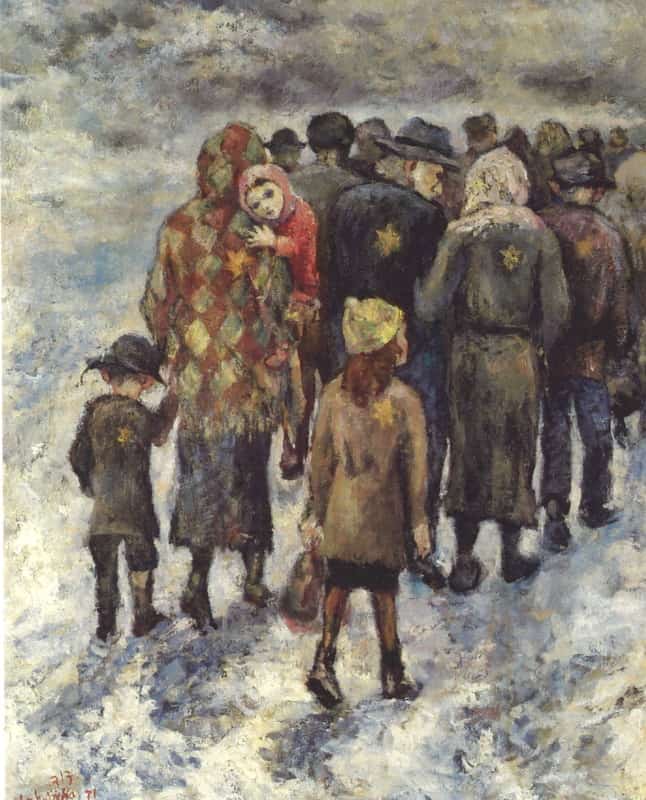

David came of age in the bustling Eastern European city of Vilna, current-day Vilnius and the modern capital of Lithuania. In the early 1920s and 1930s, Vilna was a vibrant Jewish community, often described as the Jerusalem of the North. David captures the energy of Vilna in his paintings—colorful marketplace scenes where ordinary people live ordinary but meaningful lives. He paints cobblestones and the centuries-old architecture, commerce in action, the abundance of fresh food, and the humming activity of the town’s residents.

In 1932, a bright-eyed David left Vilna to study at the Art Academy of Leningrad, a decision that would prove life-altering, though not in the ways he could have anticipated. When Germany invaded Russia in 1939, David was forced to leave the Academy and enlist in the Red Army. Shortly thereafter, he was accused of anti-Soviet activity and imprisoned in Moscow’s notorious Lubyanka Prison. From there, he was sent to the Gulag, where he endured torture and back-breaking labor for several years.

Meanwhile, back home, the German army occupied Vilna in 1941 and quickly segregated all Jews into two ghettos. In less than three years, nearly all of the Jewish inhabitants of Vilna and the surrounding area had been massacred, tens of thousands shot and left in mass graves in nearby Ponary forest. Though David escaped the horrific fate suffered by his family members and friends, he did not escape the torment of the Gulag or the ruined ashes of his home in Vilna. David and his art were forever changed.

Meanwhile, back home, the German army occupied Vilna in 1941 and quickly segregated all Jews into two ghettos. In less than three years, nearly all of the Jewish inhabitants of Vilna and the surrounding area had been massacred, tens of thousands shot and left in mass graves in nearby Ponary forest. Though David escaped the horrific fate suffered by his family members and friends, he did not escape the torment of the Gulag or the ruined ashes of his home in Vilna. David and his art were forever changed.

In 1946, David and his wife Rivka returned to then-Soviet controlled Vilna, where they lived for more than a dozen years. The city was decimated; 95 percent of the Jewish community had been exterminated. David began to piece together what had happened to his community and secretly document, through painting, all that had transpired.

Years later, David and Rivka emigrated to Israel where David was free to paint without restraint or fear of government reprisal. His first exhibit there in 1959 proved a deep disappointment. “Artistically, the work was brilliantly reviewed,” says niece Leora. “But emotionally, people could not bear to look at his art. They weren’t ready to talk about the Holocaust.”

Still, David continued to paint. As Leora notes, painting was like breathing for David. But instead of exhibiting or selling his art, David set it aside in the hopes that one day, a new generation would come to appreciate it and want to understand all that had happened in Vilna, in the ghettos, the concentration camps, the Gulags.

“I think my uncle felt a need to document what had happened. For him, it was about bearing witness to the evils and the loss,” says Leora. “If we look at ourselves today, we have this desire to post and curate on social media, to document our lives. We want to be remembered. We want people to see what we experienced and the toll it took on us. Bottomline: we want to be known. We want to be seen.”

Thanks to Leora, a new generation knows David Labkovski, sees what he saw, feels some of what he felt. The David Labkovski Project brings David’s artwork into the classroom to share lessons of life, survival, tolerance, and acceptance. As the number of Holocaust survivors rapidly diminishes, collections like David’s remain an important primary source in the study of the Holocaust. In the classroom, high school students are trained as docents who can then teach their fellow classmates about the paintings.

“It’s important to give this generation the tools to be able to educate others. By becoming docents, the students take ownership of the paintings,” explains Leora. “Peer to peer education is exceptionally powerful. It’s not just a history topic or an art project anymore. There’s a tangible aspect.”

In addition to high school curriculum, David’s paintings can be viewed digitally in online exhibits. Also available online, a Reflect and Respond Program allows viewers to respond to David’s paintings with original poems, prose or artwork. And the David Labkovski Project has developed therapeutic programming, based on David’s own self-portraiture, for rehabilitation and sobriety centers.

In his later years, David’s artwork returned to the more carefree style of his youth. A sense of gratitude is evident in his focus on nature and color. There is freedom in his brushstrokes, a renewed emphasis on light, and an embrace of life’s simple pleasures.

In his later years, David’s artwork returned to the more carefree style of his youth. A sense of gratitude is evident in his focus on nature and color. There is freedom in his brushstrokes, a renewed emphasis on light, and an embrace of life’s simple pleasures.

“I think that was his gratefulness for living in Israel. The gratitude of the sunsets and the sunrise…just being able to paint…not starving anymore…living as a free person,” observes Leora. “Sometimes people can go through terrible things, and they will never afterwards see the beauty. But David did. And he wants you to know that.”

Life to Art and Back Again: Where do we see beauty? Is it reserved for bright, happy encounters? Or is there space to recognize beauty even in the dark and difficult moments. Isn’t that what 20th century theologian and author, Francis Schaeffer meant when he wrote, “Christ is the Lord of our whole life and the Christian life should produce not only truth—flaming truth—but also beauty.”[iii]

If we learn anything from Ladi, Fahima, Samkina, and David it is this: God makes a masterpiece of all our lives. Creativity—however manifest—is a precious gift lavished on God’s image-bearers. Art in particular helps us to:

- Understand our own value in God’s kingdom

- Express more fully our humanity

- Recognize injustice and speak with a voice that transcends words

- Create space to develop empathy for others and ourselves

- Heal and restore our sense of self-worth and dignity

- Document and preserve our journeys

- Inform and teach others

Through art, we celebrate God’s breath in our lungs and the beauty of our lives—like the flower memories of the Rohingya children, or tears of gold gently falling down a mother’s face, or a sun-soaked canvas in Israel.

1 Hannah Rose Thomas, Tears of Gold: Portraits of Yazidi, Rohingya, and Nigerian Women (Walden, New York: Plough Publishing House, 2024), 42. The stories and portraits of Samkina, Ladi, Fahima and many other survivors are featured in this volume.

2 Erin Rodewald and Lou Ann Sabatier, A Retrospective: 25th Anniversary of the International Religious Freedom Act (Washington, D.C.: USCIRF, 2024), 62-63. (viewed online at https://www.uscirf.gov/sites/default/files/2024-01/25th%20IRFA%20Retrospective.pdf)

[iii] Francis A. Schaeffer, Art and the Bible (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1973), 48.