As theologically mature as we are professionally competent.

These words and the vision that brings them into being have been threading their way through my life for years. Do we want to be? Could we be? How is it possible to be? I first heard them from James Houston, founder of Regent College who left the status and security of his 30 years as an Oxford don to take up the challenge of another way of learning. At the heart of his pedagogical vision was his desire to see men and women become whole people, heart and mind, soul and strength, “as theologically mature as we are professionally competent.”

I was in my 30s when I first began listening to him, intrigued by his deeper, truer understanding of spirituality, a way of intimacy with God that had honest meaning for life in the world. While I was teaching politics amidst the push-and-shove of Capitol Hill with the world of Washington, D.C. all around, slowly by slowly I began to think through the telos of my teaching, the deeper, longer hope of my pedagogy. What was its point? What, in the end, was it about? What would good learning look like? What in fact would a good life be? And all of this written into the question of a good society, the individual and the institutional twined together, as they are. While there are many good answers to those questions, and I honor them, I chose Dr. Houston’s image—and ever since then that hope has shaped the work of my life.

Three Stories

“I’m the guy who finishes the day with sawdust in my beard.”

Years ago, I spent several days speaking to a seminary community on the question of vocation, especially looking at the ways the Church does and does not address its meaning—and so the chapel, various classes, faculty seminars, and then finally a lunch for all comers where a large room was packed.

At the end a man walked up with an eager, serious face, but with his bushy beard and flannel shirt he looked like more of an outlier to the more buttoned-down theological fraternity. I can still remember his honest eyes, telling me that he’d driven an hour to get there, had taken a longer lunch, but that he’d read my book, Visions of Vocation and wanted to hear me talk about it.

“I’m the guy who finishes the day with sawdust in my beard, so what happens here (the theological seminary) seems a long ways from what I do— but you need to know that this idea of vocation has changed the way I think about my life.”

In every way his words made my day, and I have never forgotten them. In my days there I was wrestling institutional indifference, of histories and systems that have largely excluded ordinary people in ordinary places, forgetting that most of life for most people is spent with saws and sawdust. For a thousand bad reasons the Church almost everywhere—East and West, North and South—misses at this very point, teaching that vocation is incidental not integral to the mission of God, that the work of our lives day by day has almost nothing to do with the work of God in the world.

“So, you’ve come to Vancouver to teach about vocation. Well, that’s the question of my life.”

In the years we lived in Vancouver, BC, when I was the professor of marketplace theology at Regent College, one evening I had dinner with a man whose family owned a lot of the city, and beyond. Second-generation immigrants, they had worked and worked harder, invested and invested more, buying hopes and ideas everywhere they could. That night we were at one of his venues, looking down below at the glory of his work. As we began, he said, “So, you’ve come to Vancouver to teach about vocation. Well, that’s the question of my life.”

And we spent the next hours thinking aloud and together about his life, and his labor. Accomplished in every way, and yet he too, son of Adam that he is, longed for more than prestige and property—he wanted it all to mean something, to be about something that mattered.

It was obvious that I was not the first conversation of his life about this. In and through the years he had sought out other Regent professors, J.I. Packer in particular, hungering to understand what his theological beliefs and commitments should mean for the way he lived his life. A husband and a father, a son and a brother, like all of us there was complexity to his life, and I could hear the ache of his heart, longing as he did for more coherence, a life where the personal and the public had integrity, where there was a holy and honest seamlessness that made sense of all that he loved.

“That’s the problem in Kenya, and all through Africa. We’ve disconnected faith from vocation, and vocation from culture, and though our churches are full we have been teaching a Jesus that has nothing to say about vocation, and we have corrupt cultures. Can you help us?”

One day I was asked to have lunch with Eliud Wabukala, then the Archbishop of the Anglican Province of Kenya. He wanted a “real American meal” before he returned home, and a classic diner was chosen, the menu full of Americana. He told me of his early years as a student, being chosen as one of the first Langham Trust scholars, and of his gratefulness for the generous vision of John Stott, whose own great love for the majority world brought into being a scholarship for emerging leaders of the Church from places like Kenya. Uncle John’s hope was for them to study in the West so that they could return to their homelands with PhDs and ThDs in order to grow the people of their parishes and provinces in a kind of theological maturity that the Church everywhere needs.

Years later, after serving as a pastor and then a bishop, he was appointed Archbishop for all of Kenya, pastor to some seven million Anglicans. And as we talked about his life and mine, I put onto a paper napkin the words, “faith, vocation and culture,” explaining to him the raison d’être of the Washington Institute for Faith, Vocation and Culture. As he listened, I could see that he understood, immediately and insightfully, which was when he said, “That’s the problem in Kenya, and all through Africa. We’ve disconnected faith from vocation, and vocation from culture, though our churches are full we have been teaching a Jesus that has nothing to say about vocation, and we have corrupt cultures. Can you help us?”

Sometimes we hear words that we feel deeply, insisting that they be heard, requiring a response from us. Eliud’s were like that, and in this life I will not forget them.

Each of these conversations have weight, rippling through my life, in their own ways each one a window into the longing we have for good work, and good lives, to understand what vocation means, and what our lives mean—and over many years I have had hundreds of conversations like these, with someone somewhere who yearns for something more.

The Days of Summer

Over the last few months, I have been drawn into several settings which have at their heart the hope of a pedagogy that brings into being people who become as theologically mature as they are professionally competent. In every way these invitations have been a gift to me, their programming taking me to San Diego, to San Francisco, to Calgary, and to Colorado Springs. Differently done, the grounding reasons for each have been wonderfully unique, and yet they are joined together by the desire to see men and women deepen faith, hope and love in ways that bring more clarity to the vocations of their lives, helping them understand more fully who they are, why they are, and what responsible love means as they care for their cities and societies.

Because they were where they were, and because I am who I am, my thinking about them, and for them, was distinct, San Diego for San Diego, and San Francisco for San Francisco, and on and on, and though differently done, a common vision that vocation be understood as for the common good.

I began in early May in San Diego, an event sponsored by Access Ventures who describe their vision as “catalytic capital for a flourishing society.” Always with the apostle Paul over our shoulders, listening in to the centuries, reminding us that “even your own poets have said,” we entered in by remembering Zorro, the “Robin Hood”-character whose story captured imaginations in the early 20th-century, first with a novel and then on screen after screen, film after film. With a life in and around the southern California coast, he saw himself implicated for love’s sake, a vocation with a true sense of responsibility for those in need, riding off on his black stallion night by night to step into the injustices of his day, the economic and political griefs that wounded the well-being of the people, the hoi polloi of San Juan Capistrano and beyond.

But we drew in Father Junipero Serra too, the Spanish missionary who gave his life to the building of a church along the California coastline, from San Diego to San Francisco; and because history is messy, always, we acknowledged the “messiness” of his work, at one and the same time ecclesial and missional, but by definition economic and political too. I underscored his surprising compassion for the native peoples he met, the mostly untold story that came after the final mission was established, named in honor of Saint Francis. Serra walked all the way back to Mexico City to make sure that those who sent him knew that there were “first nations” all along the coast, that the Church must care for them as the Spanish political economy began making its way north, from Baja California into what was then Alta California. History matters, and getting it right matters, if we have ears that hear.

Calling all of this, “The Sainted Story of California and the Vocations of Our Lives,” we lingered over why we see what we see, asking if we have the theological wisdom to understand the relationship of knowledge to responsibility, that knowing means caring in the biblical tradition—because being formed by true theological insight is critical for sustained faithfulness.

But we also spent time on a long work of my life, the Economics of Mutuality, the surprisingly serious effort to rethink the business of business brought into being 20 years ago by the Mars Corporation. Vocations are embedded, always, and to work on deeper questions is right, especially ones that call into question the way that things are, and instead that call us to wonder what could be, what should be.

While in a pluralizing, secularizing and globalizing world, it is always difficult to “think theologically” about the stuff of life—whether that be the arts, education, healthcare, politics or economics—that is our task, that in fact is the vocation of our lives. And it was so for the folks in San Diego, even as we gloried in the sky and the sea, we kept at the serious questions that brought us together.

As we did in San Francisco two weeks later, which was also sponsored by Access Ventures, in its remarkably creative vision it exists to nourish into being ways of working that connect financial resources with the realities of human longing and need. Because those who were there were entrepreneurial at heart—that is who they have been and that is why they were chosen—I dwelt for a time on the imaginative visions of the city’s best-known business folk. Levi Strauss of jeans and stadiums. Leland Stanford of trains and universities. Amadeo Giannini of the Bank of America, a true bank for America a century later. Hewlett and Packard of computers and more. Steve Jobs of the Apple universe, with Pixar too. George Lucas of Star Wars and much more. And North Face with its humble origins in a garage in Berkeley, which I stepped into in my dropped-out years, buying a backpack which took me all over America and Europe in the next years of my life. Father Serra and St. Francis before him could never have imagined what would someday be.

As we did in San Francisco two weeks later, which was also sponsored by Access Ventures, in its remarkably creative vision it exists to nourish into being ways of working that connect financial resources with the realities of human longing and need. Because those who were there were entrepreneurial at heart—that is who they have been and that is why they were chosen—I dwelt for a time on the imaginative visions of the city’s best-known business folk. Levi Strauss of jeans and stadiums. Leland Stanford of trains and universities. Amadeo Giannini of the Bank of America, a true bank for America a century later. Hewlett and Packard of computers and more. Steve Jobs of the Apple universe, with Pixar too. George Lucas of Star Wars and much more. And North Face with its humble origins in a garage in Berkeley, which I stepped into in my dropped-out years, buying a backpack which took me all over America and Europe in the next years of my life. Father Serra and St. Francis before him could never have imagined what would someday be.

But we also reflected on John Muir, the patron saint of California, if there is one, whose love for the Sierras has shaped the loves of generations after him. Sadly, maybe even tragically, not well-known is that he saw his explorations of the mountains as his “holy land,” a place for “sauntering” in wonder at the greatness of God’s world, which he wrote about again and again, essay after essay, book after book. (“Sainte terra” being “holy land” of course, in the Romance languages of Europe in the years we call the Middle Ages, when pilgrims were making their way to “the holy land” and began to be called “sainte terrerers,” by those whom they met on the way.) For us the question was, “What is our holy land?” What is ours to know and to love? Not likely to be Yosemite, but what in our cities, what in the wider world, calls us in, becoming a vocation that gives coherence to all that we are, to all that we called to be.

We also lingered over Augustine of Hippo with his profound insights into the human heart, exploring for the centuries that it is in the ordering of our loves that we begin to see the ordering of our lives, a truth that is as true for selves as for cities. That became artfully incarnate in the films of Terrence Malick, especially “Tree of Life” and “A Hidden Life,” in their own ways each a cinematic study of loves ordered and disordered. And all of this set within the story of California, from south to north, the golden state its own story of glory and ruin, its own story of vocations in service of God and history.

If that was California, a month later I was Calgary, with a nation-wide cohort of eager, thoughtful people from Montreal to Vancouver, each one invited into a year of serious formation by Cardus, the Canadian group committed to “imagination for a thriving society.” Asked to reflect on both the Visions of Vocation: Common Grace for the Common Good, which they have been using as a guide for several years, and also the book-being-born, Hints of Hope: Essays on Making Peace with the Proximate, I gave myself to the heart of both books, working to help them see what it is about the meaning of vocation and the idea of the proximate that gives us eyes to see more fully our place the world, of making sense of making sense of who we are, of why we are, and of what we then do with our lives.

Because the responsibility of knowledge undergirds everything when we consider vocation, I drew in some of their best poets—the Canadian singer/songwriter Bruce Cockburn, as well as the stories of their own place and people, “Renfrew of the Royal Mounted” from the Alberta Rockies 100 years ago and Alfred Hitchcock’s “I Confess,” set in Quebec City in the mid-century, as well the more contemporary drama, “Romeo Section” from Vancouver—each one giving us a window into the most primordial question of all, “What will we do with what we know?”—the question which gives shape and substance to the meaning of vocation for everyone everywhere.

But then we also listened to “Broken Hallelujahs” by the inimitable Canadian balladeer Leonard Cohen, whose poetic way with words has given people the world over language to make peace with the proximate; on the one hand being honest about the brokenness, weary and wounded as we see ourselves to be, and yet, and yet, insisting that it is a “hallelujah” that must come forth from our hearts, when all is finally said and done. I know of nothing more difficult than that—and yet, it is what each of us is called to be and to do. To see the hurt for what it is, whether that be the most personal or the most public, and to still see the world as God’s world, and therefore ours to steward, offering responsible love in and through the vocations of our lives.

And then finally I spent a week above Colorado Springs, at the Cloud Camp on Cheyenne Mountain. For the third year I have been asked to come alongside a group of wonderfully gifted forty-somethings from throughout the U.S. who gather for a few days of unusual candor and vulnerability as they think aloud and together about the vocations of their lives, one more time the questions, “Who am I? Why am I? And what then will I do with my life?” at its core.

With a grand view of the Front Range looking east and west, we met in a mountain lodge, thinking and thinking again, eating and eating again, talking into the night, the hours of our days centered on the deepest things of the human heart. With an ethos nourished by the leaders, the most honest questions are asked, the most honest answers are given, all with the purpose of entering back into the lives which are ours in the cities of America. Because I have been committed to this more coherent way of seeing, a seamlessness between what we sometimes call “the personal” and “the public,” I am attentive to the temptation of dualism, the seductively siren call to a more compartmentalized faith, and life. While nothing is ever perfect, on this mountain top there is an unusual willingness to ask and answer the hardest questions, sometimes with tears, always with hope.

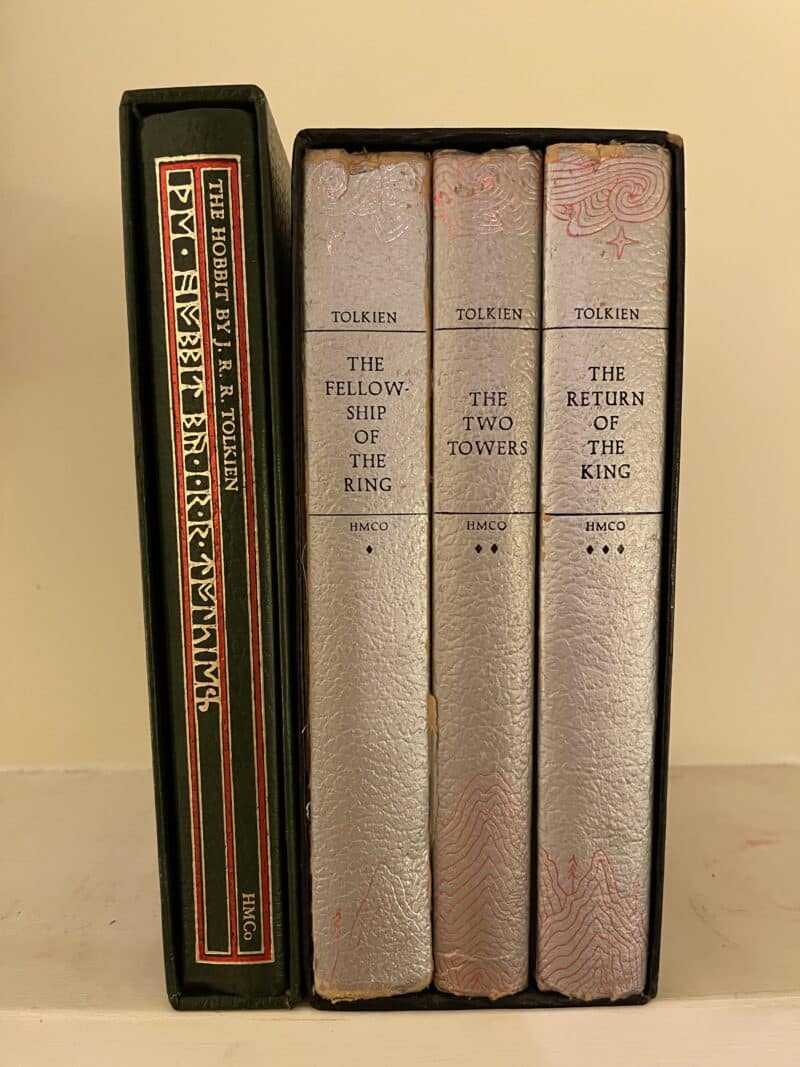

I was asked to reflect on the proximate, and chose to place it within the week-long conversation we were having about the journeys of our lives. “Isn’t it true that the best stories we know are always stories of journeys?” The Exodus. The Iliad and The Odyssey. The Babylonian exile. The Good Samaritan. The Quest of the Holy Grail. A Pilgrim’s Progress. Les Misérables. The Lord of the Rings. Are there any stories that we keep telling that are not this story of there and back again?

I was asked to reflect on the proximate, and chose to place it within the week-long conversation we were having about the journeys of our lives. “Isn’t it true that the best stories we know are always stories of journeys?” The Exodus. The Iliad and The Odyssey. The Babylonian exile. The Good Samaritan. The Quest of the Holy Grail. A Pilgrim’s Progress. Les Misérables. The Lord of the Rings. Are there any stories that we keep telling that are not this story of there and back again?

But I placed this reality within what I understand as the question of my life, the relationship of telos to praxis, explaining that I have been asking this for years, “Do you have a telos that is sufficient to meaningfully orient your praxis over the course of your life?” Where we are going, and why? What is the point of our lives, about what we say matters most to us, and how then are we living our lives? What coherence is there between what we believe and how we live?

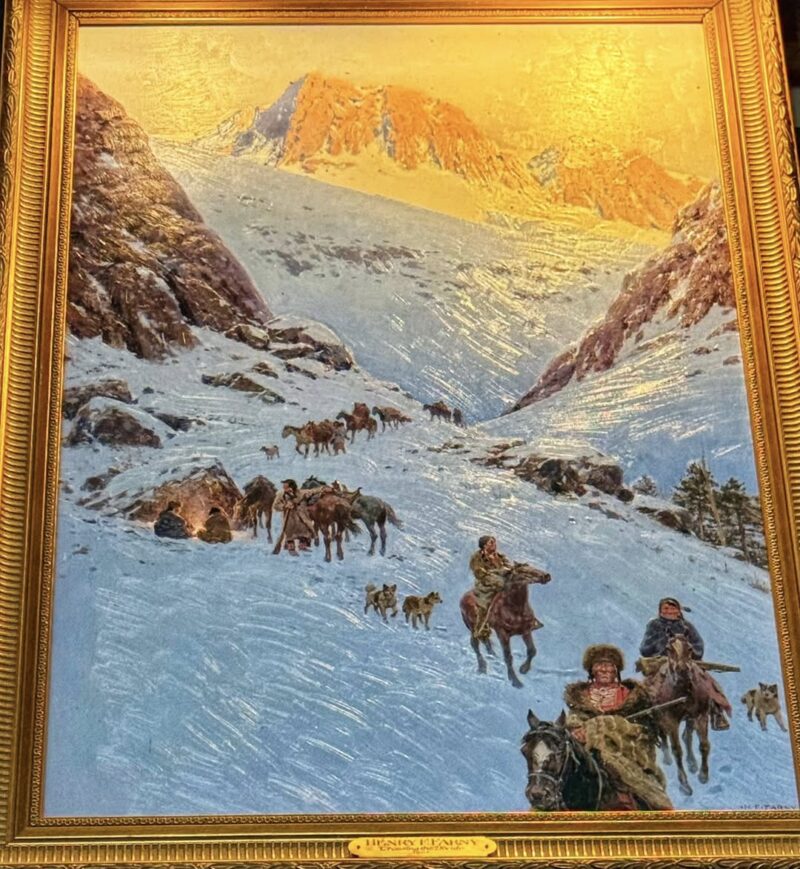

After a long day and a wonderful meal, we sat together, “the Fellowship of the Cloud” as we have come to call ourselves, in a great room filled with the best Western art, every foot of every wall, with paintings all around us of Colorado’s native peoples, each a story of a journey, of going from here to there through the grand mesas and great mountains of the American West. The walls themselves looked down upon us, listening into our conversation, and I was certain that we were being called to pay attention, true as it is that these are the stories of life, and that they are the stories of our lives, always, if we have eyes that see.

In every place I was, with every person I met, I thought of the deeper hope of the Washington Institute, committed as it has been from its beginning to seeing the integral connection between faith, vocation and culture, between what we believe about life and the world, and the way we live in the world—understanding that for blessing and curse, the cultures of history come into being because of the way that faith forms vocation. If “faith” is marginalized, if its meaning is miniaturized, tragically born of a debilitating dualism separating the sacred from the secular, one’s “Christian life” from the rest of life, worship from work, Sunday from “the other six days,” then as the good archbishop said so wisely about his own people and place, we will have “corrupt cultures.” And we do, all over the world, in America and beyond, to the far corners of the earth, and that is a great grief.

From my first conversations with the visionaries who have brought these programs into being, it was clear that their vision is for something more whole, with integrity of heart and mind at the heart. Wise beyond their years, they have developed pedagogies that by design are committed to seeing seamlessly, all of life for the whole of life, curating into being cohorts of men and women who long for coherent lives, where belief and behavior—from the most personal relationships to the most public responsibilities—are marked by unusual integrity.

Making Sense of Making Sense

As theologically mature as we are professionally competent. That vision was the reason-for-being for all that I was invited into through the summer months. There was nothing cheap about any of what I experienced; rather with remarkable professional expertise behind every gathering, with unusual organizational seriousness from beginning to end, the days marked by good food and good laughter, the hours were full, day after day—in San Diego, in San Francisco, in Calgary, in Colorado Springs—with serious people asking serious questions. To a person each seemed to understand that conversations have consequences, that words must become flesh if they are to mean anything for anyone… faith shaping vocation shaping culture, as it does. (And of course, for another day, the reverse is true too, a mysterious and profound reality that must be noted.)

But what does this look like? Threaded through each vision was a commitment to a kind of learning that is as ancient as history is, beginning with Abraham and his family on into the Exodus and beyond, extending from the 1st-century Church on through every people in every place for two thousand years. Born of a catechesis which understands that to keep going—the quests and pilgrimages and journeys that are ours—we must be people whose commitments are formed by a way of seeing life in the world, a way of learning about life in the world, and a way of living in the world… simply said, by a worldview, a mentor, and a community.

Incarnate a thousand times over the years, when learning and life become one, when belief becomes behavior, these three threads are woven through the hearts and minds of those who long to deepen their commitments and loves: 1) developing a richly-imagined, deeply-wrought theological vision that makes sense of making sense, giving us eyes to see and hear the world as God does, its genesis in a story-formed understanding of the human condition which remembers the beginning and the end of history; 2) knowing that the deepest, truest learning is always over-the-shoulder and through the heart, that what transforms us we learn in apprenticeship, seeing that words can actually become flesh, and as they do they become believable and plausible; and 3) understanding that ideas about the world eventually have to be lived in the world, and that happens first and last with others, worked out in time and space communally and corporately because it is only in a life together that we begin to understand the meaning of faith, of hope, of love. This becomes the tapestry of a more holy life, and therefore a more human life, always and everywhere.

To put it another way, these habits of heart are crucial for our flourishing, and wise ones have always known this— from the early church scattered about the Mediterranean world, on through the generations of monastic experiments of ora et labora, to more modern paradigms of serious and sustained discipleship, like the visions of Access Ventures, the Cardus NEXT/Gen Learning Communities, and the Cloud Camp, which in their own deeply distinctive ways are working out visions of vocation for the common good, seeking the flourishing of cities and societies the world over.

To become people who are as theologically mature as we are professionally competent—going further up and further into what matters most to God, to us, and to the world—is dependent upon an honest commitment to learning and living like this, each of us in our own ways weaving a fabric of faithfulness in and through the years of our lives. On this side of eternity, aching over what is not right while longing for all to be made right, we know that at our best, in and through the vocations that makes us “us,” we will be signposts of what could be, and of what someday will be… yes, day after day, “Your kingdom comes, your will be done on earth as it is in heaven.” That was the hope of my summer, and that is the hope of my life.