What does food mean, anyway? And why do we eat?

For years I have been drawn into the profoundly-formed vision of Alexander Schmemann, even beginning courses on vocation by asking my students to read his book, “For the Life of the World.” At its heart it is an exploration of the belief that everything matters, because the whole of life is sacramental— if we have eyes to see.

So he begins with food, with what we eat and why we eat. They are probing questions, going to the very center of life for everyone everywhere.

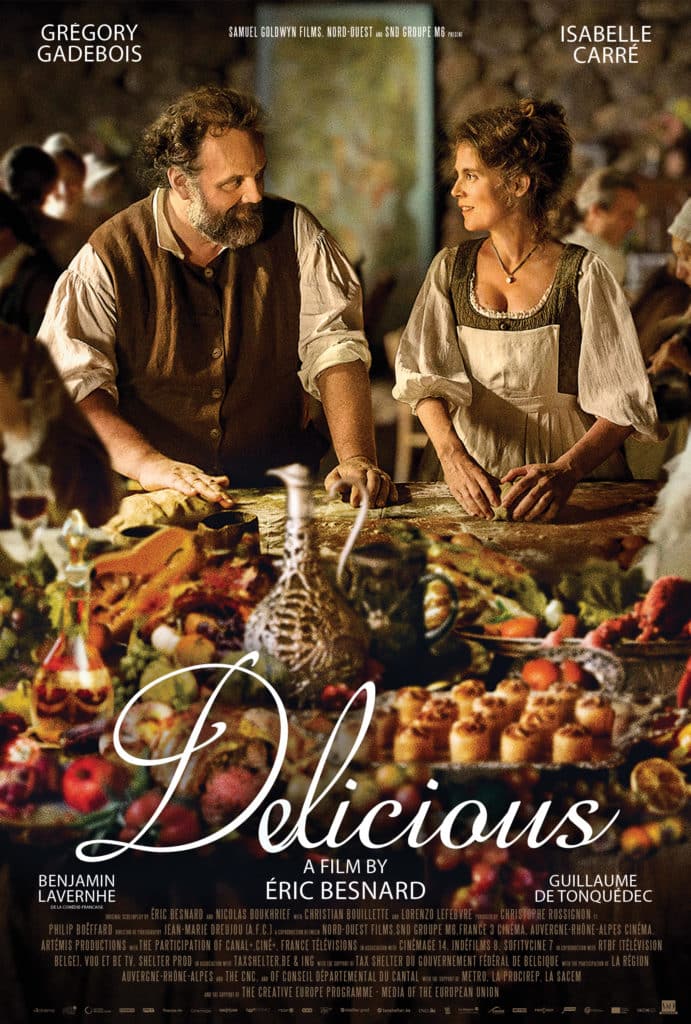

I thought of this again when Meg and I watched the French film, “Delicious” this week. Well-named, the story is of a chef in the 18th-century, just years before the Revolution, and so as it must be it is about the haves-and-the-have-nots, about those who live in the fine palaces and those who don’t, about those who see their wealth as a given and those who work and work and work simply to survive.

The film begins in a kitchen, bustling with servants of all kinds, preparing delights of all kinds, overseen by the chef who is the master of all things cuisine. The meats, the breads, the vegetables, the desserts, and the wines— he knows every inch of every oven, and with superb skill brings a magnificent meal into being.

For whom? A table of snobs, men and women who have lived high-on-every-hog the whole of their lives, sniffing and tasting, and more sniffing— and with the most elite tsk, tsk, tsk, are quick to dismiss anyone and everyone who happens to fall somehow short of their up-turned noses. Which in this story, surprisingly, happens to be the chef who has served them so well.

For whom? A table of snobs, men and women who have lived high-on-every-hog the whole of their lives, sniffing and tasting, and more sniffing— and with the most elite tsk, tsk, tsk, are quick to dismiss anyone and everyone who happens to fall somehow short of their up-turned noses. Which in this story, surprisingly, happens to be the chef who has served them so well.

The story is a story, and I will not tell it all here. But with his dismissal he leaves the grandeur of his employment, and returns home to a much more humble kitchen, not sure what he will do without the Duke to make all things possible. A well-told tale, others become part of the story too, his son being one, and later a woman who hopes to be his apprentice to learn from his culinary gifts— and with these three, the story comes to life.

As in the best stories there is mystery and suspense, and I will not ruin that. Over time the chef finds his way into his work again, imagining and preparing the most wonderful food for all who make their way to his inn for a good meal, even a grand supper. (And with a smile, there is a playful allusion to the very first restaurant ever! And to the first-ever try at French fries!)

But there is a twist to the story, one we know because we know our own hearts. Throughout history, almost always, the rule of every day is eye-for-eye, tooth-for-tooth. You slap me, I will slap you. You take mine, I will take yours. The film wrestles with a deeper truth, metaphorically and parabolically, as good stories do. There is no grace in “Delicious,” simply said. Even with the glory of the roasted meats, the wonder of the mouth-watering pastries, and more and and more and more, there is only wound upon wound. A grief given, a grief taken.

A beautifully-told story, even a very understandable story— who among us does not want revenge? for good reasons! —but there is no grace because that is beyond the cultural pale in pre-revolutionary France, and tragically in most times and most places.

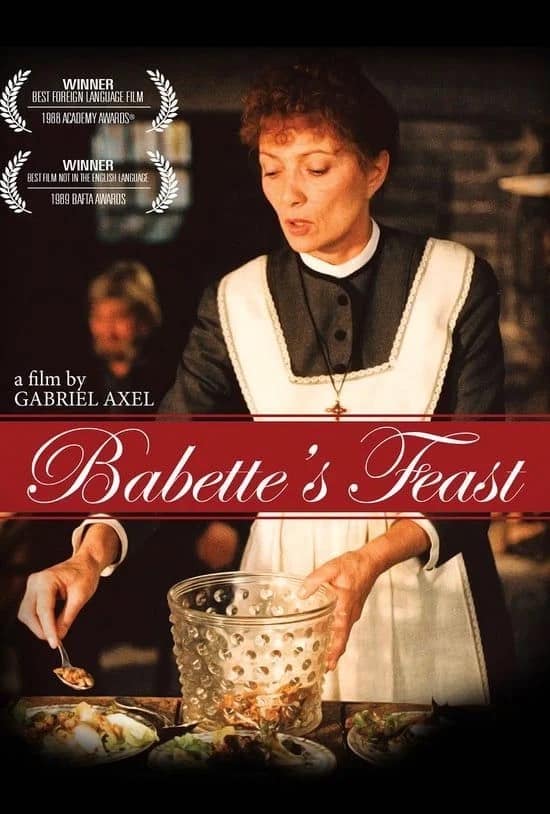

The longer I watched, the more I thought of the Danish film, “Babette’s Feast,” a similar story, but born of a different world and worldview. Despair and disappointment, grief and sorrow, hurt upon hurt, resentments that only deepen, and then… a great grace. A feast, of all things. Generously imagined, skillfully created, surprisingly offered, people who have not talked to each other for years, slowly by slowly begin to eat and drink together around a common table— and are perplexed, then pleased, at the transformation of their hearts as they taste and see the wonders before them… each one a gift from Babette, a woman from Paris with her own mysteries, who chooses to give herself away for the sake of others, knowing in her heart of hearts that the most important things of the whole of the universe become alive to us in the gift of a meal.

What we eat, and why we eat what we eat is in reality the great question of life, from creation to consummation, from the trees of the Garden to the marriage supper of the Lamb, with “passovers” and “last suppers” and more threaded through the Great Story that it is, a sacramental story of heaven coming to earth— if we have eyes to see.

Schmemann knew that, reflecting with unusual wisdom about our raison d’etre as human beings, about human vocation necessarily being “for the life of the world”— and so he began with food.